Given the reasons that restorative practices in schools could be a good idea (see those reasons here, here, and here), why aren’t all schools adopting restorative practices? Based on my experiences in restorative practices—teaching, researching, and consulting with schools—I’ve come to see eight prominent concerns.

1. Schools are not ready for restorative practices

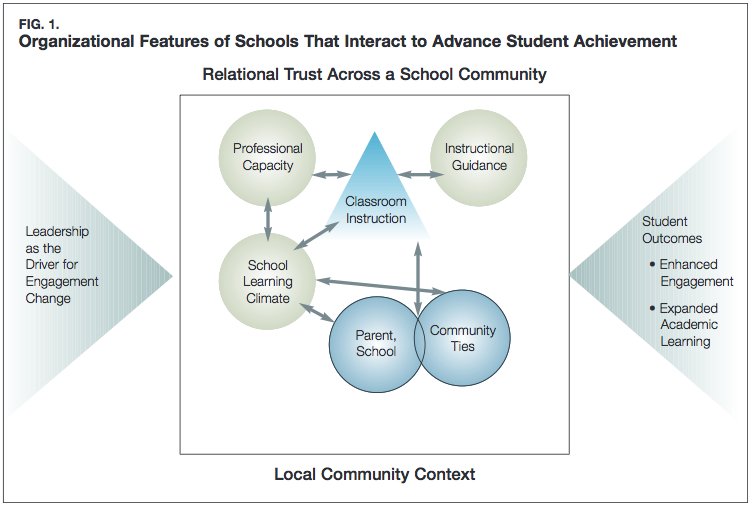

There likely are a variety of things that need to be in place before restorative practices can be implemented. One of the most comprehensive models for thinking about how to improve schools suggests that among a variety of important features, concerted leadership must drive change for a capable staff (see Figure 1 below). Moreover, sometimes district-level policies for schools must change. For example, some districts mandate their schools to structure their days in ways that don’t allow for successful restorative practices.

2. There isn’t conclusive evidence that restorative practices work

Three high-quality studies (1, 2, 3) are in progress to address this lack of evidence. However, I have reservations about these studies positioned, by default, as THE evidence because they are all linked to one way of thinking about restorative practices. I believe that the best restorative practices are implemented to fit the unique needs of one school, and these studies’ methods employ a proscribed approach to restorative practices. A proscribed approach is necessary for researchers to effectively compare implementations to each other—otherwise they would be unfairly comparing schools with different approaches. As mentioned in this blog post, a school should implement a core set of practices and beyond that, a school might choose from an array of practices that make it a better fit. Moreover, I haven’t been able to learn how the approach used in these three high-quality studies sufficiently account for meeting all the needs alluded to in possibility 1 above.

3. Restorative practices are complex

One need only take a look at an implementation guide to realize that they will likely need help to implement restorative practices.

4. Conceptual and buy-in problems

When consulting, I’m often asked by school practitioners for demonstrations or media portrayals of restorative practices in action; yet, there is a dearth of relevant online videos. Others seem to be more interested in restorative practices only when they’ve heard the success of restorative practices at schools with similar problems. Once convinced, some schools think of restorative practices as a “magical cure all” for social and behavioral problems at school. They should intentionally use restorative practices to address identified needs as alluded to in this post.

5. Consumer-driven, program-based market ideology

Many administrators are skeptical of anything packaged as a program because resource-intensive programs—that promise results—already overwhelm them; many of them don’t quite deliver. Restorative practices can be thought of as a set of practices and not a packaged program; although, some implementations are packaged as programs. Some administrators are wary of the tensions between consumer/market driven approaches to programs and honoring the well-being of their students and teachers through implementing something tailored specifically to their needs.

6. Concerns about extreme behavior

Many states still allow for corporal punishment and some schools actively threaten to use this form of punishment to deal with extreme behavior. Some school leaders have voiced skepticism about the rare folks that likely wouldn’t respond to intense restorative practices and have yet to be convinced that all humans would respond.

7. Restorative practices (high structure, warmth, and support) don’t fit with some leadership styles and needs

Some evidence (see review: Spera, 2005) suggests that authoritarian leadership styles (high in structure and low in warmth and support) can actually be helpful for distinct ethnic, gender, and social groups of youths. Separately, some administrators perceive restorative practices as taking away from their power as administrators because restorative practices include a lot of warmth and support. It’s not clear to them how they may maintain high structure with a lot of warmth and support.

8. Contextual-based inequalities may prevent implementation of restorative practices

Preliminary evidence suggests that contextual social, economic, and political forces seem to associate with fewer implementations of restorative practices for some race, ethnic, and socio-economic groups. Some suggest that unequal access to alternative practices are intentionally designed, others suggest that they are a result of poorly designed policies, and still others suggest individual-level approaches.

I’ve encountered these reasons throughout my consultation experience and have witnessed multiple well-intentioned administrators turn down restorative practices for their schools.

A few administrators have later opted to implement restorative practices when we’ve had time to comprehensively address these issues. Given this, explanatory and implementation materials would do well to address concerns.

I find it interesting the discussion of “warmth.” In my mind, the word warmth could be replaced with empathy. Increasing “warmth” or empathy in schools is seen as “taking away their power as administrators.” Let’s be clear, empathy is not weakness and “administrator power” is rooted in violence. Most schools maintain a model of domination, not cooperation. Administrators sub-consciously know that if they have greater empathy with their students, and see them as living, breathing, creative, loving beings, that their model of domination will fall apart. Thank you Joseph for this insightful article. It is important to understand where the resistance is in schools.

I’m glad that there seems to be some utility to what we’ve shared here. 🙂

Your consideration of clarifying warmth with empathy is a very important one. Another term folks use is “responsiveness.” Regardless of the term, it seems that the important component of this is that adults understand how their students feel and help them to adaptively respond to such feelings.

Thanks for commenting and I’m wondering if you’ve had experiences of working with administrators who choose models of domination. I’m curious about what are the reasons for why these administrators resist engaging empathetically with their students. Also, do you have any success stories for helping shift such a school administrators’ frame of mind?