Metta Center note: Restorative Solutions is holding a training on restorative practices in schools in mid-June. The training will be held over 3–5 days in Arizona. Applications due by June 8. Learn more and apply.

As I wrote previously, Restorative practices (RPS) are increasingly employed in schools to address discipline in ways that keep students engaged with their learning.

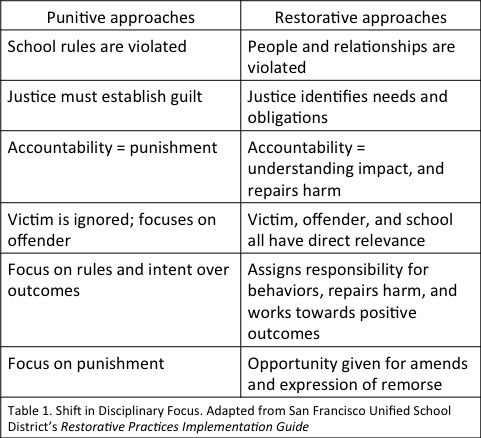

To keep students engaged, RPS develop person power to bring about democracy and social justice in schools. They shift disciplinary foci (see table below). By doing so, they represent a fundamental change towards discipline that may engender discomfort and resistance among educators asked to embrace RPS. Among many concerns raised during consultation with educators, two seem to re-emerge.

One reason concerned educators experience discomfort is that they perceive a disconnect between the skills students learn through restorative practices that happen at school and the social skills that students might need to use outside of school with hostile police, gangs, or other harsh situations. Educators are also hesitant because they are fearful that RPS reveal the real sources of problems; to them, people who participate in RPS are ultimately engaging in futile exercises because they won’t be able to address sources of problems that exist in broader socio-economic and political structures. Examples of these sources might include poverty and systematic exclusion. They are worried that RPS might teach youth to reproduce neo-liberal tendencies where addressing problems are relegated to the individual and away from broader structures. Although these concerns are well-intended, effective RPS address fundamental needs such that both concerns are misplaced.

One reason concerned educators experience discomfort is that they perceive a disconnect between the skills students learn through restorative practices that happen at school and the social skills that students might need to use outside of school with hostile police, gangs, or other harsh situations. Educators are also hesitant because they are fearful that RPS reveal the real sources of problems; to them, people who participate in RPS are ultimately engaging in futile exercises because they won’t be able to address sources of problems that exist in broader socio-economic and political structures. Examples of these sources might include poverty and systematic exclusion. They are worried that RPS might teach youth to reproduce neo-liberal tendencies where addressing problems are relegated to the individual and away from broader structures. Although these concerns are well-intended, effective RPS address fundamental needs such that both concerns are misplaced.

First, RPS teach emotional and social skills that are fundamentally relevant to real world situations. Over time, students are taught how to understand and recognize their emotions such that when they feel heightened emotions in a harsh situation, they are better able to choose to calm down (i.e. disengage from fight or flight responses) and access their ability to make more effective decisions. Moreover, the core practices of RPS promote a students’ ability to engage in empathy. If educators invite local police to participate in RPS circles, use restorative language throughout the process, and talk with students about what police(wo)men’s experiences are in hostile situations, students might be better able to respond in these situations. Police(wo)men might also learn more about the students. Similarly, conversations may be held with students to address their experiences with neighborhood gangs.

Second, RPS at schools are not designed to address larger social problems by themselves. Community organizing, legal advocacy, community development, action research, and restorative practices used on a city-level are designed to address those problems. Again, RPS provide the fundamental skills to understand and then act to address broader social problems. By using RPS, participants may more clearly identify sources of a problem, clarify and articulate an issue, and build collective understanding and power to address an issue.

Given the fundamental relevance of RPS, these concerns are misplaced because they are concerns about pedagogical philosophies. Namely, how are educators making learning more relevant? Also, how are educators and concerned adults linking education with social change?