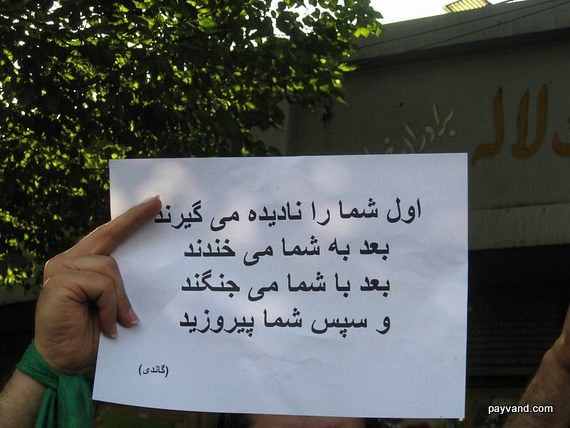

…at a rally on June 17:

Translation:

“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” — Mahatma Gandhi

Dear Friends,

We are a group of professors, students and activists of [[nonviolence]] who work with nonviolent movements and we would like to extend to you our solidarity and encouragement for your struggle. Based on our experience, we would share the following thoughts with you at this critical juncture:

Your cause is just. Despite the blackout, people all over the world are following your struggle and our hearts are with you. To have a just cause and courage are the two main requirements for a nonviolent movement, and you have both.

What you have done already is to open up a bridge between the people of Iran and the people of America and many other parts of the world. Your protest has created an emotional bridge with people everywhere — for who does not love freedom? — and shown us in the West in particular that many, many Iranians are just like us, and not the hardliners our media have often portrayed you to be. This is a great achievement that has already changed history.

This is a critical hour. History has shown repeatedly — even your own history — that success will come in exact proportion to your ability to remain nonviolent under even extreme provocation. Gandhi insisted that apathy and cowardice are the worst forms of violence. You have moved far beyond apathy, and cowardice. But now you can take the greater step of maintaining nonviolent discipline. This will not only help you keep the support of world opinion behind you but will make you stronger and — in the end — much more effective. Hatred can dislodge oppressors, but it cannot build freedom. Remember the great discovery of Martin Luther King:

Our movement caused no explosions of anger . . . It controlled anger and released it under discipline for maximum effect.

How to do this. [[Nonviolence]] does not mean standing idly by when women and children — or anyone else — are being attacked. It does mean doing everything possible to prevent such attacks on innocent people and if absolutely necessary intervening even with force to protect them. We do not seek out such situations, but if we suddenly find one we are justified in putting our bodies in the way of harm to protect others and in extreme cases, if there is no other way, using force on would-be attackers. If we can do this without fear or hatred, or more realistically, to the extent that we do it without fear or hatred, we are being nonviolent. However, remember that this applies only in emergencies.

How not to do it. Nonviolence definitely does not include:

- targeting individuals, even Basiji, for harm. The cardinal principle in all nonviolence is that we are never against persons, only against injustice. In an important hadith, the Prophet (pbuh) told his companions to help everyone, even an oppressor. When asked, ‘How do we help an oppressor?’ He replied, “”By preventing him from oppressing.”

- using hateful, inflammatory language. “Death to the dictator” should never be said. As far as possible, it should never even be thought. Hate dictatorship, not dictators or their minions.

- Chanting slogans may help to create a sense of community, but after a while that energy would be better “harnessed,” as Martin Luther King found, “for maximum effect.” A night of silence — not imposed, but self-imposed as a matter of discipline — can give a sense of more power than a night of shouting.

Let us turn to some of those proven methods.

In a strike it is very important to not only be against something, but also for the alternative you desire. Often this takes the form of Constructive Programme, where the people perform for themselves the services that the regime is providing — or withholding. For example, in Mexico when protestors were boycotting a major bread-baking corporation (the largest breadmaker in the country and a key financier of the fraudulent elections in 2006) the women began baking bread on their own, which developed into a grassroots industry (Pan Mi General).

This can also take the powerful form of parallel institutions: schools, clinics, the media, or other services that are under the control of an undesirable regime can be substituted by the people themselves, as was done in Palestine during the First Intifada.

Finally, it is very important to create community throughout your efforts, as in part you have done by forming small groups, we understand, during massive protests. These communities will form the backbone of a more democratic society.

Despite the crackdown, you should not be discouraged. We want to assure you of our heartfelt support and encourage you to continue going forward and to be nonviolent to the greatest extent possible. As Martin Luther King said, “unearned suffering is redemptive.” Our greatest wish is that you would not have to suffer at all, but if you must endure further suffering, know that if you do so without retaliating, as the Pashtuns did so conspicuously in the Northwest Frontier Province in the 1930s, and if you have a well-thought-out strategy that uses constructive methods wherever possible and obstructive methods where necessary, you must eventually succeed, not only for yourselves but for the world.

[…] about Mexico Violence as of June 25, 2009 Thursday, June 25, 2009 An Open Letter to Sisters and Brothers in Iran – mettacenter.org 06/25/2009 …at a rally on June 17: Translation: “First they ignore you, […]

Thanks for your support. mA piroozim!

Democracy must be practiced. I encourage all of your readers to use collaborative Wiki sites like the one I linked to w/ my name to share information about your upcoming local elections. Change must come from the bottom up.

Unfortunately this regime has no conscious and will use nonviolence movement as a weakness and to their advantage, and continues beating, arresting and torturing. At this juncture it is imperative to answer baton w/ baton. When the ruthless basij thug fears his own safety, that he might be subject to baton too, he will refrain from using his, or the knife, gun, etc. When we see innocent standby like Neda (May her soul rest in peace) is murdered cold blood, and we see so many thugs w/ knives slashing young men and women, nonviolence approach becomes ineffective and without purpose. The thugs who are committing the slaughter of my brothers and sisters are mostly brought in from other countries, are well trained, and emotionally weathered for the job. They are well paid cold blooded mercenaries that money is the only thing in their minds. They have no sympathy for Iranians except their own pocket. Some are brainwashed fanatics who believe it is god given mission to them to eliminate non –believers. They laugh at your nonviolence approach and love this method dearly, since it makes it much easier for them to finish their job. This struggle now has taken a new form. It is a war between a ruthless System and the people. You cannot win a war w/ bare hands when the enemy is pointing guns at you. You will lose. The enemy has used tear gas to disperse the crowd. The gathering has no chance to gain momentum and people eventually are discouraged. Nothing accomplishes then, only at the end a few badly beaten and injured or killed. This Regime knows this game and is well experience at it. Has done it for 30 years. They will continue their ruthless tactic until people are finally haplessly accepting their condition and go home looking into future. Iran is at a tipping point now. The future can be changed for better or worse. I will guarantee you- if today’s movement is squashed like all others in the past, Iranian people will let the regime be and dare to go through another up rise like this one for a long time because of the suffering , the injuries, the killing and the incarcerations and tortures. This will give Ahmadinejad enough time to get his bomb and accomplished his mission – which is dropping the bomb on Israel as he has promised.

Essi55, I resonate with your anger towards the regime and the atrocities that you have witnessed. We have never said that to be nonviolent is to lack rage. In fact, rage towards this unconscionable brutality is essential to nonviolence, and we believe nonviolence is essential to bring about a shift toward democracy. You suggest that raising your own baton (or knife, or gun) will discourage the basij from using his. Isn’t it more likely that it will only increase the brutality of his response in his attempt to defeat you? If you then increase your own brutality to the level where you can prevail, the new regime you will have established will depend on the ongoing continuance of this brutality for its existence. Is that what you are striving for? The end will be determined by whatever means you choose to bring it about; a violent revolution will bring about a violent regime. If democracy is the intended result, nonviolent means are imperative.

You have correctly named this as a conflict between a “ruthless System and the people”. “The System” you speak of are the methods of violence, threat, and domination. “The people” includes all people caught up in that system, including those “thugs” and “fanatics” who are also victims of that system (did you not say yourself that they are brain-washed?) as much as they are perpetrators. The goal must be to eliminate that System and replace it with peaceful means of governance, not to attempt to eliminate people through adopting the System’s methods as your own, thereby perpetuating that System indefinitely.

Today over half of the world’s population lives in a country that has experienced a significant nonviolent event, most of which had a successful outcome. How is it that so often people who use violence are defeated by those who do not? What do the nonviolent resistors use as their weapon? To quote Sergei Plekhanov, an observer of the failed 1991 coup in Russia which was successfully defeated through nonviolent means, they have prevailed only through “spirit, a sense of legitimacy, and the willingness of some people to risk their lives.” Resisting violent force through these means requires sacrifice, and at times suffering and loss of life, but is ultimately the only way brutality itself can be defeated.

To tell the truth, I’am speechless. The Shawshank Redemption is great. I’am a young film fanatic, as a matter of fact, this movie is realised the same yearI was born, and thence I’am to a greater extent accustomed movies with marvellous special effects, edge-of-your-seat action, et cetera. This movie has zero of that, and nonetheless, it close to me . Way Frank Darabont uses the tale of Red to drive on the tale, the beauty of the music used (note the harmonica used merely earlier Red getting the letter at the end). The whole movie, from beginning to end, from actions to music, is a beacon of hope, judgment, and redemption. The cast is perfect, Morgan Freeman(Red) really brings about a refreshing feel to the story, and that is precisely what the movie is, what a film should be. Really recommended for each film fan.

for a second time, several weeks were a few. Well another article that will work out just fine. I need this article just finishing up, and it has the same theme as yours. Thanks, happy trails.Click Here

Great read. I found your website on yahoo and i have your page bookmarked on my personal read list!

I’m a fan of your site. Keep up the great work

I won’t be able to thank you sufficiently for the blogposts on your site. I know you placed a lot of time and effort into these and hope you know how deeply I enjoy it. I hope I am able to do the same for someone else sooner or later.

I was, nonetheless, reluctant to sign this letter in part because of my suspicion that the press would mischaracterize my measured expression of concern with incendiary terms like “torch ” and “lash out, ” which is, of course, exactly what they did. I have never met Pastor Warren but I have long been an admirer of his ministry, even when I disagreed with him in significant respects. I have read many of the criticisms of his “Purpose Driven ” concepts, including strained allegations of “New Age ” associations, but I am unconvinced that he is other than a reasonably orthodox Baptist. I, therefore, did not want my opposition to Senator Obama’s involvement in the Saddleback conference to be misconstrued as disapproval or ingratitude for Pastor Warren’s leadership on the important problem of AIDS.