By Michael Nagler and Stephanie Van Hook

Tamayo and Mitsuo do not have to demonstrate this week. Our friends from Hiroshima (Mitsuo founded the Center for Nonviolence and Peace in that city) had been going out every week to protest the construction of a new nuclear plant; but this is no ordinary week for the people of Japan, who have seen first hand the horrors of nuclear bombs and now face the threat of nuclear meltdowns.

Today, faced with the possibility of serious nuclear fall-out from several units of the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant, the Japanese government has issued a temporary freeze on the construction of new plants, leaving many, many people like Tamayo and Mitsuo to attend to their fellow citizens in need, and to appreciate one another. This, at least, is a strange and painful victory amidst an ocean of catastrophe, and within it we can see a valuable teaching moment for an entire world culture on the brink of collapse and societal, not only nuclear meltdown. The catastrophe was a form of violence — the violence in nature, abetted by violent practices in the human world. We should be asking, what is a nonviolent response?

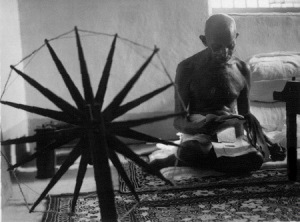

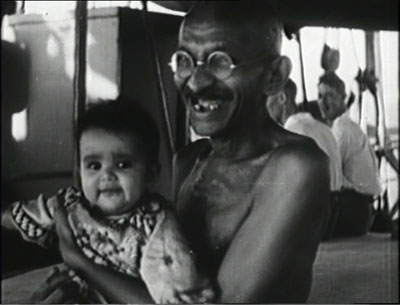

While nonviolence has recently attracted the attention of the world because of its dramatic successes in, for example, Egypt, that is only a fraction of its potential. Nonviolence is closely linked to the innate creative resources in all of us, though to be sure there is a kind of perverse creativity that can be roused by violence also. “We are constantly being astounded these days,” wrote Gandhi, “by new developments in the field of violence. But I maintain that even more astounding developments will be made in the field of nonviolence.”

And he was right. To illustrate this, let’s look at a slower, even more man-made catastrophe. A neighborhood in North Philadelphia had been made unlivable by the tensions caused by structural violence of racism and poverty—those slow cancers of our society. Apathy ruled, no one had a higher vision for deliberately creating neighborhood of vibrant beauty, assuming that as it must eventually hit bottom, and something better would arise from the ashes. This is a dangerous kind of thinking that has actually driven some to accept nuclear holocaust by its apocalyptic logic. This is why we take this story as potentially an allegory for our entire situation. Artist Lily Yeh, however, had a different vision for this neighborhood. She helped to transform it into a viable, healthy village rebuilt by the hands of the children who called it their home. Where others saw destitution, she saw the potential to create something, the raw material of beauty. What she did — rousing people to do the needful from local resources without waiting on governments — would be called in nonviolence “constructive programme.” It is the other half, along with the kind of active resistance we saw in Egypt, of what people can do to rebuild the world in the only way that it will stay rebuilt.

Like Lily Yeh, we have to believe that in spite of collapse, if not because of it, there is potential for us to actively create a more beautiful world from the toxic wasteland on which our planet at present ebbs. As our colleague, Prof. Randall Amster, has recently written, “It’s all too easy to slip back into complacency, and by now many are no doubt suffering from a sense of ‘disaster fatigue.’ . . . the ultimate disaster would be to ignore this most recent alarm and hit the snooze button instead.”

Like Lily Yeh, we have to believe that in spite of collapse, if not because of it, there is potential for us to actively create a more beautiful world from the toxic wasteland on which our planet at present ebbs. As our colleague, Prof. Randall Amster, has recently written, “It’s all too easy to slip back into complacency, and by now many are no doubt suffering from a sense of ‘disaster fatigue.’ . . . the ultimate disaster would be to ignore this most recent alarm and hit the snooze button instead.”

What Lily Yeh did we must do on a much broader scale. We are faced with not a neighborhood but a stricken world. We cannot go on simply rebuilding cities or factories after every setback; we are at a limit. There is no such thing as a ‘clean’ war with no collateral damage (all damage damages all, on some level); there’s no such thing as a ‘well-built’ nuclear reactor that won’t turn into an environmental monster in the next quake or leave behind unspeakable poisons that endure ten thousand years.

Even if there were, the problem with the consumer culture we have built will not go away. It will still depend on constant “growth” and the obsolescence of ever-more-useless goods. Worse, it will still go on commoditizing values, ultimately even of people.

It will still promote an illusory habit of mind whereby whenever anything fails ‘we’ll get a new one.’ We’re not going to get a new planet — or a life.

It was Gandhi, again, who put his finger on the core of the problem a hundred years ago (102, to be exact) when he pointed out, in his famous pamphlet Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, that we have built a civilization based on the multiplication of wants instead of the satisfaction of needs.

It is interesting that in Tokyo today, as friends there are telling us, while chain stores and super markets have yet to get their complex systems back on line, local suppliers and mom-and-pop grocery stores are feeding people.

The Japanese people have responded to their crisis with their traditional courage, generosity, and selflessness. It is inspiring to all of us. But it is not enough. We must honor their suffering and their self-sacrificing resilience, but take it further: we must get out of this consumerist civilization altogether. To do that we will have to learn to live simply, to argue strenuously, and to fight nonviolently when the powers that be try to ignore us.

thank you for this article. You’ve got my constructive wheels turning.