In the spring of 2005 I stood on the roof of the Student Union building in Berkeley, overlooking Sproul Plaza, where I had lived through the exhilaration of the Free Speech Movement four-plus decades earlier. Milling about behind me were about thirty or so young adults, the youth contingent of the first Spiritual Activism Conference convened by Rabbi Michael Lerner and myself. It was impossible not to compare “then” with “now,” and I found the comparison instructive, even inspiring.

In the spring of 2005 I stood on the roof of the Student Union building in Berkeley, overlooking Sproul Plaza, where I had lived through the exhilaration of the Free Speech Movement four-plus decades earlier. Milling about behind me were about thirty or so young adults, the youth contingent of the first Spiritual Activism Conference convened by Rabbi Michael Lerner and myself. It was impossible not to compare “then” with “now,” and I found the comparison instructive, even inspiring.

Listening to them, I ticked off the critical mistakes we had made in those heady days of protest, and it was immensely reassuring to note that the folks around me had made a lot of headway correcting them. Back then we were, of course, dead set against racism, or tried to be (the FSM was an aftershock of the Civil Rights movement) but these young people were totally color blind. I heard even more progress in an area we had barely touched on: fully integrating women as true equals. We famously “didn’t trust anyone over thirty” (that became a bit awkward for me in ’67 when I slipped over the line!), but the concept of “mentor” had subsequently come in to make it acceptable to benefit from an older person’s experience — absolutely critical for a movement facing, as we still do, sophisticated, if wrong-headed, opposition.

I had fond memories of cafes where we sat arguing about Camus and Marx (not that we read the latter), which was a really good thing, but none of us, as far as I remembered, was fully aware what was happening to the earth, not to mention getting our hands dirty in her by growing food, or building composting toilets; a few of these people, by contrast, had come fresh from their organic farms up in Oregon, still in coveralls. And then the most important change, in my view: we had been in a state of near-total ignorance about nonviolence. They were considerably more sophisticated of nonviolence, and happily that awareness has taken another leap in the last few years.

But one thing that had not sat well with me in 1964 was not much improved in 2005 and is still an issue today in the amazing #OWS movement: the issue of leadership.

Leaderless movements, to be sure, are not the aimless, decapitated things they are taken for by mainstream commentators, and OWS in particular has dealt with the issue good-humoredly. I believe it’s Occupy CO that anointed a border collie, Shelby, with her backpack, as their official spokescreature. “She is more like a person than any corporation,” they said.

More to the point, leader or no leader, it is succeeding to some degree in keeping order and charting a course for itself — backing away somewhat from contested sites and switching “from places to issues,” wisely. Yet for this and any future progressive movement I feel that a philosophy, a vision, and a strategy for realizing that vision will be essential, if for no other reason than the clear, consistent, and compellingly simplistic message of conservatives. And for all this, as well as sheer efficiency, leadership could be of enormous help.

Can we have a kind of leadership that could help us stay more focused, more efficient, than the “horizontal,” everything-by-consensus style that has been the political culture of progressive movements? Can we relax somewhat the ideological aversion to leadership that has come to dominate progressive thought — and, I think, slowed the movement down — and open ourselves, to some kind of discriminating leadership that will not inhibit individual responsibility — for many of us feel, myself included, that individual responsibility lies close to the core of the world we want?

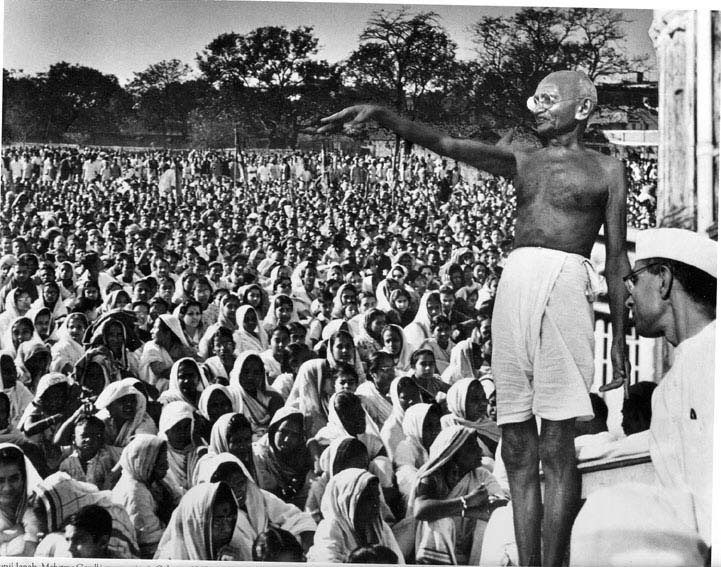

I believe that we can; in fact, this kind of leadership was one of Gandhi’s most striking achievements. No one was able to evoke the self-leadership potential of his followers while still giving tight focus to huge campaigns — calling off whole Satyagrahas (campaigns) when even a few people were unable to contain their own violence, directing the switch to “constructive programme” when direct resistance became unworkable, etc. Some feel it was Gandhi’s greatest contribution to turn ordinary men and women into heroes. As many of us know, when he and virtually the whole leadership was arrested during the Salt Satyagraha of 1930 leadership devolved, successfully, onto every individual.

Yet, while it may seem counterintuitive (most of my students were shocked to hear this), in the heat of struggle Gandhi said, “I am your general, and as long as you want me to lead you, you have to give me your implicit obedience.” How is this different, to take an extreme example, from Hitler telling his generals when he launched the disastrous campaign in Yugoslavia (a blunder that in fact cost him the war), “I do not expect my generals to understand me; I expect them to obey me”?

Well, in two ways. For one thing, there’s that qualification, “as long as you want me.” Gandhi said he would drop out the minute the people did not want him, and did exactly that when the congress Party couldn’t see their way clear to following his pacifism in WWII. Secondly, he did want his people to understand him. From the earliest days in South Africa he toiled day and night to bring them along, often insisting they understand in detail the full significance of anything to which they agreed. Moreover, his concept of “heart unity” — that if people want one another’s fulfillment they are one despite any differences of class, status, or whatever — applied to leadership. Never did he feel superior in anything but responsibility and the willingness to suffer to anyone following him. As he said, “Diversity there certainly is in the world, but it means neither inequality nor untouchability.”

Of course, Gandhi sets the bar pretty high! But a high bar makes the qualities we need at least visible, something to strive for. The opposite of bad leadership, then, may not be no leadership, but good leadership — and followers alert enough to tell the difference.

It is quite interesting that reading Camus and talking about Marx did not give you to think of nonviolence. This is because of their tradition, which has systematically omitted the topic as a fundamental issue. Even their century could not give them to recognize Gandhi adequately, if at all! This stunning, devastating occlusion is inherent in the truth of the history of Being, so much so that even the greatest philosopher of the question of Being, Heidegger, utterly failed to recognize this in certain critical ways.

It is possible to reconceptualize leadership through the concepts of enarchy and econstruction. These entail design that observes an ethics of self-deconstructability, thus enabling partial or even at times great “submission” or sub-ordination, if the grounding philosophy for this is “open source”. It is one thing to conceive of such a thing as a peculiar parenthesis with coined words; it is quite another to realize the same in nonviolence thoughtaction or ahimsa satyagraha in decisive envolution emerging within the activated engagement with the fundaments of the culture of the likes of Camus and Marx, et al. The problem lies in the business of referencing such authors without a decisive confrontation with their tradition. This confrontation can be realized with concepts such as those I am invoking here, such as “thoughtaction” and “envolution”. Such envolutionary thoughtaction may be as deep as one wants it to be and perhaps as the world needs it to be, while the “en” is the very spirit of the Gandhian en-joining to the others in their own leadership and voluntary subordination, variously. The turning in the of the “de” and the “an” of ‘deconstruction” and “anarchy”, respectively, in the form of the “en” is the spirit of what lies beyond revolution and leaders simpliciter. The complexity embraced in the sad departure from the simpliciter presents the problem of the sense of self released from the organizing principles of negation and leaderhip into the new en-ergy, the en-working of envolution, which I term enmusic, provisionally, as the awakened but grounded en-ergy in gravitas of nonviolence thoughtaction or ahimsa satyagraha. I offer this term as a response to the predominant force of negation in reactive nonviolence and the culture of rage. The term “music” is useful and appropriate for a number of reasons which may as well obtain fundamental envolutionality through, for example, reference to Nietzsche, who viewed a decisive confrontation with Wagner, the musical composer, as essential for the accomplishment of the self-overcoming he vaunted. Likewise, it constitutions a decidedly envolutionary gesture with respect to the role of rage in music as it currently capitalizes itself within dominant culture. This capitalization, however, extends beyond rage as such and entails a rethinking of the process of virtuality and sublimation in media culture whose role can not be dismissed as regards its systematic rerouting of world en-ergy into virtual experience. Taken together, the enmusical experience of world is a positive formulation for *satyagraha*. As I said, it is meant to be, at this time at least, provisional as it obviously has a weak cache. It is not clear whether this weakness is intrinsic to the term as such or to the status of music and the poetic in the world.

Some of these are quite obviously new words and can be easily dismissed as either bizarre or too eccentric for use. However, they can be stipulated and developed quite rigorously, and that rigor is part of what is needful in the realization of “this movement” at the fundaments that will remain considerably occluded and active in infelicitous ways without these turns. Thus, whether one calls it “envolution” or not, it will entail the posture of what “en” means and what “volution” means, for example. Whether one calls the work “enconstructive” or the structuring “enarchical” or not, the gesture will be that of the “en” and pertain to structure and archical structions of leadership and design; this is the logic of a good obtaining of a term: the terms will, nevertheless and aside from mere preference continue to have the best nominative value anyhow. The terms themselves are fundamental acts of satygraha and are self-instantiating, since they are themselves variously enarchical, enconstructive and envolutionary.

Their path of truth is satyagraha and spinning and observes, it apparently must be noted, a situation of transcendental constitution that must adhere to most rigorous orders of being and can not admit of artifice or artifact, preference or simple imposition of meaning as a merely willful coining of words or events. Such is the inner truth of satyagraha, although many would seek to challenge and master this from a certain outside that fails adequately to understand the conditions of truth in the world. We must not challenge or seek to control or master truth too much lest we poison it with our artifact and, convinced of mastery, lose truth in the process. The progression of such thinking is of a piece with satyagraha, just as the word itself, as a hybrid and essentially “spun” tem was and is, linguistically, a self instantiating actual realization of satyagraha. This is the state of the world, while truth limps along behind or buried in the storms and enterprises of a challenging, righteous certitude above, riddled with paths lined with the red flags of artifice and will. There is no such artifice in Egypt today, yet we would not dismiss such satyagrahi as not yet “fully” satyagrahi, pending a manufactured “stamp of approval”, trademark, artificially imposed judgement or mastered Truth. Indeed, it is precisely these latter things that have held back nonviolence most of all.

That satyagraha can or should happen in thought as such, in its own way, may not be evident. But this has to do with the status of thought today. “And yet, it could be that prevailing Man has acted too much and thought too little.” (Heidegger) It is worth noting a recent kind of action undertaken in India involving creatin of solutions to the problem of litter. In that case, the activists, who eschew naming themselves or taking credit for their ad hoc actions, do not put their emphasis on the actual act of cleaning as such, but on *thinking* as their primary vocation, in the form of developing effective solutions. This is also satyagraha or thoughtaciton. It is important to realize that thinking can be intrinsic to and even at times the better part of action. The foresmost thought for such thoughtaction today must be the decisive confrontation with the dominance of the idea of Action as transcending thought.

It must be noted, however, that these conceptual “moves” are themselves are all inherently neutral. The act of remembering nonviolence in this context is essentially envolutional, neither simply revolutionary nor awaiting evolution, it emerges as one realizes one is given to this remembering to remember, to insert, instantiate, enstructure ones thinking to include this independent fundament.