By Metta Blogger Philip Wight

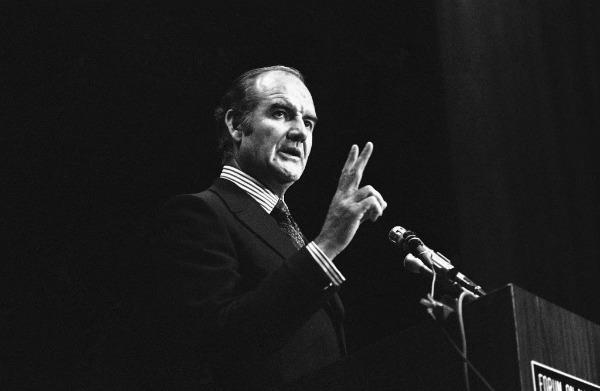

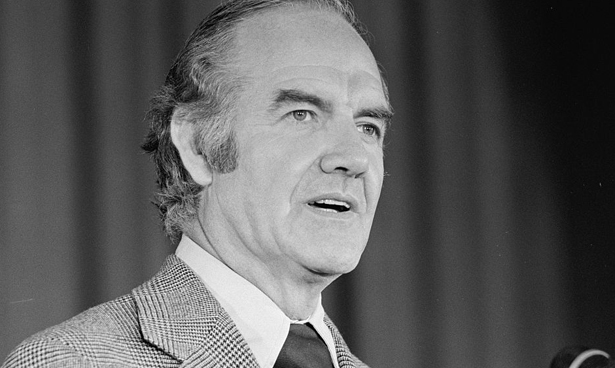

This past Sunday, October 21st, former U.S. senator and presidential candidate George McGovern died at the age of ninety. Since his death, newspapers and the internet have buzzed with tributes to the “idealism” and “optimism” of the late McGovern, especially praising his role as a “peacenik” during the Vietnam War.

But McGovern was not a pacifist. He flew over thirty-five combat missions as a B-24 pilot during World War Two and held firm to the argument that military force was necessary to stop Hitler. While he was the first senator to speak out against military engagement in Vietnam and would become an anti-war celebrity, McGovern voted for the Gulf of Tonkin resolution and for tens of millions of dollars in additional war funding. Yet he later regretted voting for the Tonkin resolution—which allowed the President to escalate the conflict—and crafted the first drafts for bills to de-fund the war, which eventually stopped the conflict.

For all his faults, McGovern’s legacy reveals a man who strove for peace amid the exigencies of Capitol Hill. After WWII, McGovern earned his B.A. on the G.I. Bill and even won a Peace Oratory Contest as an undergraduate. He pursued his passion for studying the past and earned a Ph.D. in History for Northwestern University, which deeply informed the soon-to-be politician. Elected to the US Senate in 1962, McGovern spoke out against America’s embargo of Cuba, rising military spending (he called for a $5 billion dollar budget cut), and exporting weapons abroad. Especially in regards to Southeast Asia, he cautioned against repressing nationalist movements and supporting imperialist nations.

For all his faults, McGovern’s legacy reveals a man who strove for peace amid the exigencies of Capitol Hill. After WWII, McGovern earned his B.A. on the G.I. Bill and even won a Peace Oratory Contest as an undergraduate. He pursued his passion for studying the past and earned a Ph.D. in History for Northwestern University, which deeply informed the soon-to-be politician. Elected to the US Senate in 1962, McGovern spoke out against America’s embargo of Cuba, rising military spending (he called for a $5 billion dollar budget cut), and exporting weapons abroad. Especially in regards to Southeast Asia, he cautioned against repressing nationalist movements and supporting imperialist nations.

McGovern’s concern for peace stretched far beyond military budgets and exporting weapons though. After entering Congress in 1960, McGovern became the first director of the Food for Peace program. Raised in rural poverty, McGovern empathized with the poor and argued that food security was a key element to world peace. Harvard historian and JFK insider Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote the Food for Peace program had been “the greatest unseen weapon of Kennedy’s third-world policy.” In the later sixties, McGovern addressed America’s poverty and expressed shame that hunger existed in the world’s richest nation. His efforts led to the introduction of the food stamps and school breakfast and lunch programs for those in need.

Throughout his years in Congress, McGovern struggled to balance his principles with the imperatives of Washington politics. As the war in Vietnam escalated, McGovern denounced the war and addressed hundreds of thousands of anti-war protestors on the National Mall. But shortly after these speeches, he rejected the confrontational direct-action tactics of the anti-war movement, dismissing these strategies as counterproductive, “reckless,” and irresponsible. McGovern wrestled with the classic dilemma: how does one remain principled while being politically effective?

McGovern refocused his attention on legislation and power of Congress to revoke the war’s budget. While Congress rejected his proposals, the majority of the American people supported de-funding the conflict. Rather than back down in the face of defeat, McGovern redoubled his efforts and rhetoric. He told his fellow senators—in starkly moral language—that they were responsible for sending “50,000 young Americans to an early grave.” In reaction to a fellow senator’s suggestion that American troops would have to invade Cambodia, McGovern offered his pithiest anti-war argument: “I’m tired of old men dreaming up wars for young men to fight.”

His firm anti-war stance catapulted Senator McGovern to run against President Richard Nixon in the 1972 election. During the campaign, McGovern rarely mentioned his wartime experience and the impact of WWII on his struggle for peace in Vietnam. Pundits and historians argued this was his greatest fault—that the American people needed to be reminded he was not a pacifist, but a realist veteran who had witnessed to cruelties of war. Yet McGovern’s presidential campaign should be remembered for his constructive vision; he called for a continuation of the civil rights campaign, protecting the environment, and ensuring equal opportunity for women. And historians cannot ignore the foil of the 1972 election: while Nixon “won,” he did so through mendacity and criminality—and while McGovern “lost,” he never sacrificed his veracity and courage.

McGovern never allowed his political missteps to defeat his principles. He counseled new legislators, “If you want to be a good member of Congress you have to get over the fear of losing an election.” His precept to never “throw away your conscience” earned him Robert Kennedy’s praise as “the most decent man in the US Senate.” McGovern continued to speak his conscience in his final years and argued against the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan as repetitions of Vietnam.

McGovern’s legacy reveals deep ironies and hard truths about the politics of peace in America. He was a combat veteran derided as a pacifist, a peace-seeker who regretfully voted to escalate the war, an anti-war orator who spoke out against the confrontational tactics of the anti-war movement, and a historian aware of the tide of anti-colonialism but unable to overcome the imperialistic politics of America’s foreign policy. An imperfect human (like us all), McGovern’s legacy echoes with idealism and failure, vision and pragmatism, and principles besieged by bitter politics.

In remembering McGovern, we should not overlook his missteps, but see the senator as a man of moral courage in a world governed by self-interest and expediency. We’d be a better people if we supported more “losers” like McGovern who never contemplated losing their principles.