By: Mercedes Mack

In 1989, students in Kiev, Ukraine, had had enough of Soviet occupation and politics. Two student groups, the Student Brotherhood (March 1989) and later the Ukrainian Students Union (December 1989) formed a coalition against Soviet influence. Initially, student groups staged protests and strikes in response to concerns regarding higher education-abolish compulsory courses in Marxism-Leninism, ban on campus operations of KGB and CPSU, protect students from persecution for political activities, etc. Demonstrations by students and Ukrainians included- taking an oath of allegiance to an independent Ukraine, and demonstrations outside KGB headquarters. Responding to a call from opposition parties on Sept 30, 1990, 100,000 students gathered in Kiev in solidarity against a proposed Union Treaty (a proposition by the Kremlin to strengthen ties among republics of the Soviet Union).

On Oct 1, 1990, on the first day of the Soviet Supreme’s second session, 20,000 people protested in the streets and workers organized a one day warning strike. Taking note of the political climate and wave of support, the student coalition regrouped and formed an achievable list of demands, inclusive to that of the grievances of Ukrainians.

*Resignation of Soviet Premier and establishment of multi-party elections.

*Abolition of the proposed Union Treaty.

*A law ensuring Ukrainian military conscripts only delivered military service within Ukraine.

*Nationalization of Communist Party property.

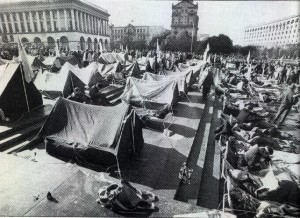

On Oct 2, 1990 a group of 200 coalition students launched civil disobedience in support of their demands. The students occupied what they renamed Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Freedom Square), official name Lenin Square, in Kiev, initially erecting about 50 tents. This is the same square that would be later occupied by the Orange Revolution some fourteen years later. A core group of 200 students participated directly in the hunger strike, while many others joined to participate in the general strike over the next several days, increasing support to thousands of people. Opposition members of Parliament also joined, and solidarity swelled to about 15,000. Students were inspired by the student demonstrations in Tienanmen Square, and adopted similar tactics, namely nonviolent techniques of hunger strike and occupation. Having witnessed the severe crackdown of the People’s Republic of China, organizers were resolved in their nonviolent methods.

Student hunger strike, ‘Independence Square’, Kyiv, October 1990

“We went in with cold minds, prepared for any kind of conflict, but with the conviction that the only real path open to the government was peaceful.”

The movement continued to gain support at an alarming rate. Workers from the Arsenal factory (a pro-communist establishment) in Kiev declared support for the students. Students all over Ukraine had either joined the strike in Kiev, or staged sit-ins in solidarity at their local universities.By mid October, universities had become paralyzed due to lack of student attendance.

On Oct 15, movement demands were read aloud outside of parliament by one of the student organizers, Olis Doniy and nationally broadcast. Government acquiesced within two weeks of 15 days of the initiation of the hunger strike. On October 17, 1990, Parliament agreed to restrict the Soviet military within Ukraine (volunteers excepted), dropped consideration of the proposed Union Treaty, and several months later, Prime Minister Vitaliy Masol resigned and the Supreme Soviet agreed to allow multi-party electio ns.

Although successful in getting most of their demands specifically met, the government did not keep their promises long term. Youth were shut out from participating in politics in any official capacity. Government imposed age limits on candidates and leaders that were able to participate faced great difficulty entering a majoritarian political system.

Olis Doniy reflects, “At that time young political leaders had the possibility to realize their ideas, just as there was also the possibility for the state to incorporate them. Unfortunately, the state squandered the opportunity… in fact, ideas about the complex social and political reforms in Ukraine were to be found exclusively within the young political elite, in the student organizations.” I would add one more thing to Doniy’s reflection- that the students were also partner to the post revolution events. An option for the Granite Revolution could have been to go back to civil resistance when government acted in ways that went back on their promises. Gandhi used this strategy many times during his movement for Indian Independence. He would stop satyagraha when the British cooperated and was always open to constructive dialogue, but when the British went back on their word, or were not willing to cooperate, he would resume satyagraha. This is reflective of the fluid nature of civil disobedience-there are many victories and many setbacks, but the movement should never hesitate to re-initiate satyagraha when it becomes apparent that the adversary is no longer keeping their promise.

For more reading:Youth As An Agent For Change: The Next Generation In Ukraine