By Michael Nagler

San Quentin may you rot and burn in hell, may your walls fall and may I live to tell;

May all the world forget you ever stood, may all the world regret you did no good.

San Quentin I hate every inch of you,

I’ll walk out a wiser, weaker man

Mister Congressman why can’t you understand

Johnny Cash

At 12:45pm on Friday, May 27, the gates of San Quentin State prison closed behind me. I had come, with Metta Vice-President Cynthia Boaz and her colleague at Sonoma State University, Dean Elaine Leeder, to give a workshop on nonviolence to some thirty men who were in the prison for fifteen years to life for crimes of violence, mostly homicide.

The criminal justice system is one of the most broken and corrupt of many systems that are failing us in the United States — particularly here, as comparable democracies in most parts of Europe, not to mention a few countries like New Zealand and Rwanda, have experimented with indigenous systems based on an entirely different principle that are far more effective. For Cyndi and myself, this was our first visit inside one of the nation’s prisons.

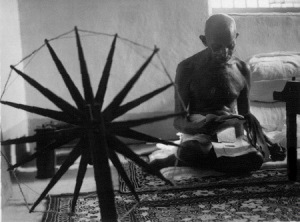

I began by sharing with the men that when I recently told someone that I promote nonviolence she shot back, “What kind of violence?” Nonviolence is all but totally unfamiliar to the average person, not because it’s not there (as Gandhi said, it’s “as old as the hills”), not because it’s in any way unnatural, but because we are so wrong, in this “thing-oriented” civilization of ours, about what human nature is.

In our culture the human being is still regarded as a body, separate from the rest of reality, doomed to compete for scarce resources, ultimately through violence — basically a “bag of genes” (as one scientist recently put it) without transcendent meaning in a random universe. But science has made remarkable breakthroughs in the last quarter century that bring inspiring confirmation to what the wisest human beings have always said: that no, despite possible appearances, we are not material bodies acted on by chance. We are not separate, not at all condemned to competition and violence. We are not — life as we know it is not — a ‘finished product.’ Cooperation is stronger than competition even in ‘raw nature.’ We are conscious beings endowed with choice (and the parallel responsibility) and have only begun to realize our potential.

In this ‘new story,’ nonviolence makes perfect sense. Gandhi called it, “the greatest power at the disposal of humankind.” When mobilized in large groups over sustained periods, it has utterly changed history, ending the colonial period and in our own country dealt a blow to racism. According to Gandhi, who is so far the only person in history to have experimented with nonviolence on a large scale over fifty years and ‘reduce it to a science,’ it is the only force that brings about lasting, positive change. The reason for this is precisely that it belies all the falsehoods about human nature that we’ve just mentioned. It elevates both the person offering it and the person to whom it is offered. The word ‘nonviolence’ very poorly represents this all-important capacity. That is why I consider the Tagalog term for nonviolence that came to the fore briefly during the Philippine “people power” uprising of 1986 a vast improvement: alay dangal, to ‘offer dignity.’ When someone threatens you, he or she is offering you disrespect, in extreme cases trying to humiliate you, along with harm. He is treating you not as a person who can be coerced through fear. When — and this is the key element — we refuse to let that fear master us (not even to feel it is an advanced stage reached only by very few); when we refuse to do something we regard as unjust but refuse to hate the person trying to get us to do it, we are retaining our own dignity and not only treating them with respect, despite their behavior, but offering them a chance to stop disrespecting us. And perhaps more than a chance:

“What Satyagraha does in such cases is not to suppress reason but to free it from inertia and to establish its sovereignty over prejudice, hatred, and other baser passions. In other words, if one may paradoxically put it, it does not enslave, it compels reason to be free.”

The recent discovery of “mirror neurons” has shown an actual neural pathway for this compelling effect Gandhi refers to.

In addition, we are refusing to go along with the lie of radical separateness the threat situation represents, the ultimate lie that one person can benefit by harming another. Disrespect and separateness, closely linked and both false, dehumanize us. As Gandhi said, “nonviolence is the law of the humans,” because nonviolence of his conception means respect for all that lives and what he called “heart unity,” the faith that, as Martin Luther King said, we are all embraced in “an inescapable network of mutuality…a single garment of destiny” regardless of the differences that may appear to divide us on the surface. The truth of nonviolence has a good deal of power, and that power comes into our hands, as Gandhi maintained, when we can love our enemy. Not sentimentally, perhaps not emotionally, but spiritually, with this kind of faith and courage. When we resist an impulse to hate or fear the considerable energy of those drives is converted, often without our awareness, into creative action of the kind that, on the large scale, brings down dictatorships and changes history. That inner change accomplished, the rest is strategy.

What would a criminal justice system look like if it were based on this vision, this power? Fortunately, the question is not entirely theoretical. The men were quite familiar with restorative programs like the Prison Ashram Project, Alternatives to Violence, and others. Some of them knew about the remarkable, and successful approach to youth crime that has been adopted in New Zealand, where an offender sits down with his or her direct victims and representatives of the community to discuss what led him or her to offend, how the alienation he or she caused can be repaired and other problems adjusted. They also knew that education — which we were engaged in — is a powerful antidote to crime (and other forms of violence). Where the national recidivism rate hovers around 70-73%, among prisoners receiving degrees while incarcerated it drops to 12-33%; among the graduates of the program we were engaged in it drops to 2%.

If nonviolence ‘offers dignity,’ and education is a powerful way to restore dignity, imagine the power of nonviolence education: and not only for those many whom we have incarcerated, but for all of us.

We begin this education as soon as we take off our moral glasses and putting on educational ones. We stop saying to the offender, as Bo Lozoff of the Prison Ashram Project likes to put it, “Hey, get outta here!” and start saying, “Hey, get back in here.” We stop regarding him or her as incapable of changing — a potently self-fulfilling prophecy of our current criminal justice system. We reverse the decision explicitly made in 1976 to change the purpose of the State of California penal system from rehabilitation to punishment.

There are two features of successful experiments in restorative justice, whether urban or indigenous, that are both easy to explain from this new perspective: first, as is well known, the offender must accept his or her responsibility. Responsibility is in a way the opposite of guilt: it empowers, guilt paralyzes. Responsibility is for something you have done, not something you are. When you own your responsibility you become fully human. Note that two major, defining institutions of industrial life begin by trying to shelter individuals from their responsibility: the publically traded corporation and the military. This brings us to the second common feature.

In restorative systems, the crime affects the whole community, and its resolution is effected by the whole community. In a society like ours where violence and materialism and massively promoted by our powerful mass media, what kind of hypocrisy could maintain that an offender acted on some isolated impulse: in effect, jjust as he or she must own responsibility, so must all of us. And in addition, any act of violence sends shockwaves through an entire society — including the violence of caging a human being. Nonviolence is ‘truth-force’ (a rough translation of Satyagraha); in restorative justice the lie that human beings are the result of chance and that we are radically separate from one another is confronted by the truths that each of us is a responsible agent, whether for good or ill, and none of us is unaffected by the acts, words, or possibly even the thoughts of others.

I suggested to the men that they could learn all they could about nonviolence, avoid exposure to the commercial mass media, consider taking up a spiritual practice (nothing like it for counteracting the dismal image of the person in commercial culture), humanize their relationships with one another even — especially — in that dehumanizing environment, and finally get involved in some project that is open to them to make the world a better place. I hope I made them feel that their efforts, their lives, matter and spiritual forces are not stopped by walls.

But we have a long way to go. Despite the proven power of education, and of nonviolence, we conducted our workshop in a prison laundry, shouting over the voices from a class on the other side of the wall. On our way across the crowded yard after the workshop we stood looking up for a while at the grim walls of death row.