Originally published in Waging Nonviolence

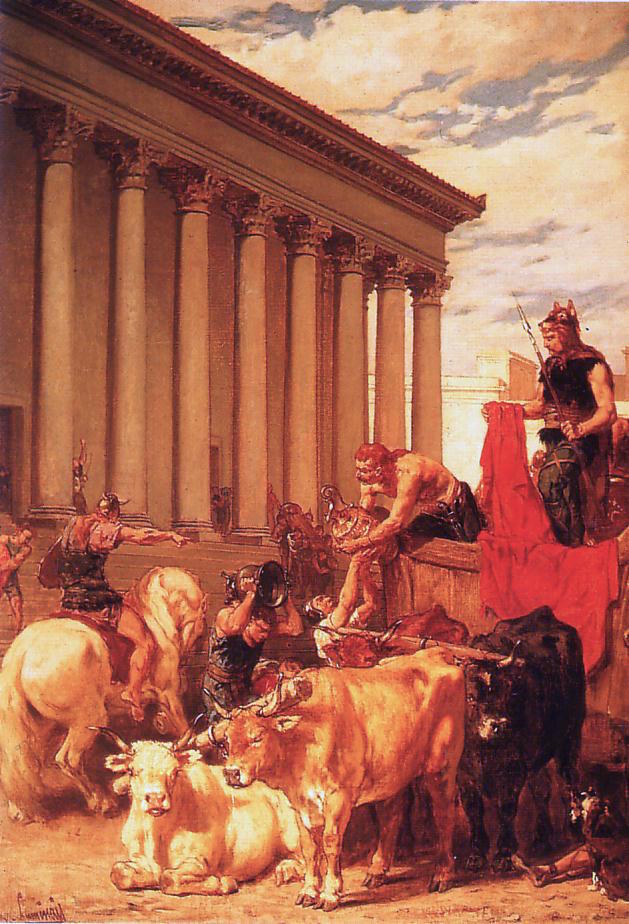

On Aug. 24, 410 C.E., Alaric with his army of Goths entered Rome and sacked the capital of the empire. The shock echoed throughout the circum-Mediterranean world and Europe: How could this happen to the “eternal city”? Though the scale of the attack was so much smaller, and it failed, many people throughout the much larger modern world today were shocked that this could happen to the “indispensible nation.” There are other differences, of course. The Roman emperor did not call down the attack on his own city! Nor did any senators join in the carnage. The Goths were an outside enemy, not Roman citizens, and were a relatively disciplined army, in contrast to the disorganized mob that attacked the Capitol Building on Jan. 6. But one cannot help seeing a parallel to the affront to the capitol, and wonder if there’s something we can learn from it.

In response to the events of 410, St. Augustine created his mighty classic, the “City of God.” He did it to reassure Christians that their abandonment of their pagan gods had not brought this punishment down on them, but along the way he managed to build a comprehensive vision that laid the foundation of a Christian order that prevailed through the Middle Ages. He was building on the essentially Jewish discovery of the unity of God, and by extension the unity of all creation, including the human family. It is no coincidence that this work includes the first in-depth discussion of peace, to my knowledge, in Western civilization. This is the component into which today Pope Francis has been breathing new life, for example with the nonviolence retreat hosted recently by the Vatican.

Perhaps we were lucky. The sack of one building, however central to our democracy, is very small relative to Rome. But, if we take it as the wake-up call it is, we can indeed find some clues to where to go from here that are, in their way, as grand as Augustine’s project. Kaitlyn Tiffany writes, in an article that appeared in October and was recently reprinted by The Atlantic, “This will change your life: Why the grandiose promises of multilevel marketing and QAnon conspiracy theories go hand in hand:”

I think this emptiness of meaning is the core of our problem. As the Washington Post reported on Jan, 13, “QAnon theorists were involved in every level of planning and carrying out the Jan. 6 insurrection;” and surely QAnon could not be swallowed for a moment by large numbers of otherwise adult people if they were not grasping at straws for some sense of purpose, of stability. Nor would the puerility of video games and action movies, which furnished the scenario in which the crowd could figure as the heroes who were saving the world. The world is in fact going through a crisis of meaning that will lead to more outbursts like this if we do not somehow fill that legitimate need.

We have somehow to do what Augustine did: come up with a worldview that gives meaning and stability, such that people would have no need to grasp at fantasies like QAnon or take to destructive violence to act them out. The worldview would not need to arise from the Judeo-Christian worldview specifically, but it would certainly want to be in harmony with the Wisdom Tradition, as the late Huston Smith called it: that vast cultural heritage of human traditions that hold out a vision of humanity as evolving spiritual beings in a meaningful universe.

Until recently, Augustine had an advantage over us: The science of his day, such as it was, offered no serious competition to the Christian worldview. He carried out many arguments with Neoplatonic and other philosophical schools (which carried more weight than the science). He was able to prevail, in my view, because Cristian scripture furnished a better way to talk about the inner life, which was what the world at that time was looking for.

Until recently. The material science and material worldview that has dominated Western civilization for several centuries seemed to deliver an airtight explanation of reality based on the random motion of material particles, and gained great credibility when it was able to deliver a dizzying surge of technology and material abundance — including very real advances in healthcare that we would not wish to be without. But when push came to shove it failed to account for the most vital endowments of the human being — our emotions, the intellectual achievements that distinguish us from the other animals, consciousness itself. A bit over a hundred years ago now the theoretical underpinning of materialism was exposed to the glare of quantum theory, with its discovery of the primacy of consciousness and “non-locality” or interlocking unity of existence. Come down to today and you find physicists talking about “non-local consciousness,” biologists unearthing precious legacies of cooperation running throughout evolution, psychologists leaving behind Freud’s misguided focus on disfunction to work out a “positive psychology” — and Gandhi gifting the world with nonviolence and daring to claim that “nonviolence is the badge of the human species.” Even military personnel now, faced with the trauma suffered by troops who are not wounded in body, are now speaking of “moral injury” — the harm caused by hurting others that they tried to make recruits shed through the dehumanization of military training.

One group of “new scientists” — this movement is often called “new science” as opposed to “classical,” i.e. materialist science — has formed an Association for the Advancement of Post-material Science. The fact is, we need post-material everything. Starting with a post-material image of the human being. The vast common inheritance of human wisdom in virtually every known culture has unwaveringly maintained down the centuries that we are endowed with, if not actually are, spirit, soul, or call it what you will. We now possess innumerable scientific experiments showing that we can affect one another at a distance via what scientists call “subtle energy.” We can influence to some degree how quickly others heal, what they’re thinking, even the neuronal activity of their brain. As one group of researchers showed, when two subjects meditate together for some time and then are widely separated, with both wired to fMRI devices and only one shown a flashing light, the other’s brain will show the same rhythmic firing. The point here is not to refute Einstein, who famously refused to believe in “spooky actions at a distance,” or to make a case for parapsychology, but far more importantly to make us aware of our full humanity; to save us from feeling “like gypsies in the universe,” as one writer put it, and feel good about the undiscovered capacities inside us — and take responsibility for how we use them.

Above all, it is to make us aware of the undeniable connection among us. It is inspiring to imagine the changes that would follow this awareness. Racism, which is after all based on a reaction to physical difference, would disappear. As Gandhi said, “Even differences are helpful where there are tolerance, charity, and truth.” Most kinds of alienation would be substantially resolved, taking off with it vast amounts of the depression, hostility and meaninglessness plaguing human life today.

Post-material economics would go on from E.F. Schumacher’s famous “economics as if people mattered,” relieving the earth of its crushing burden as people stopped frantically trying to make themselves happy by manufacturing more, buying more, eating more, throwing away more than they could ever need — often at others’ expense. Think of the relief of the people themselves when they realize that frantic consumption isn’t working, and they don’t need it. They can start working toward happiness where it does come from: rich relationships, meaningful work, ways to serve, etc.

Another name for nonviolence, of course — at least the kind Gandhi and King employed — is “soul-force.” it would cease to be a mystery that nonviolence works at a deeper level to improve relationships and social arrangements, while violence, as Martin Luther King said, “solves no social problems; it merely creates new and more complex ones.” Violence would be revealed as against the grain of human nature, while nonviolence springs from it. Like other natural endowments, to be sure, it has to be recognized, learned about and trained for if we are to deploy it for meaningful change. But at the heart of it is a simple change of attitude: where violence would say that a person is a problem, nonviolence would counter, no, that person has a problem. On the solid basis of this new attitude, which really implies, at bottom, a different worldview, highly successful nonviolent work can proceed through the trajectory of personal empowerment, constructive action and resistance where necessary. Given strategy and training — and we’re getting better at both — it’s not hard to imagine that we can build a new order out of the present chaos.

There are people right now hard at work on this “new” worldview (which has been around for millennia). This work is building the infrastructure, or less metaphorically, the conceptual framework that will bring many forward-looking experiments already going on in the fields of nonviolence, economics, education, popular culture and science itself into prominence. It will support suggestions being made, for example just now by Maria Stephan’s article in Waging Nonviolence, “We need to prepare for ongoing insurrectionary violence and address its root causes.” But this effort needs to stop being the preserve of a few specialists; all of us can help by simply familiarizing ourselves with the outlines of the new story — starting perhaps with the simple formulation offered above, that we are evolving spiritual beings in a meaningful universe — and talking it up wherever there’s the opportunity. Consider it your personal “Constructive Programme” that, like the spinning wheel in Gandhi’s program, can be done by any and all of us and be not only a set of effective actions but a concrete expression of our common purpose.

We have a new president. Let us give him a new mental climate to make his work fruitful.