In this blog-series accompanying our project of updating the Peace and Conflict Studies lectures (we call it PACS 164-c), Kimberlyn David reviews some of the key material of the course from a personal lens in an effort to generate personal reflection and the application of course content.

That Western yoga and spiritual practitioners often quote Gandhi without acknowledging his political achievements should give us a lot to think about, and learn from. You’ve likely guessed which quote is most often used: “Be the change…” There’s no record of Gandhi actually saying those words, yet they stick.

It’s not hard to understand why. They sound and feel good. They give the hope that systemic changes come about by trying to be decent people alone. They seem to say, “There’s no need for getting involved with messy, ugly politics—just be a nice person.” If only that were the case!

On my first day of yoga teacher training in 2011, I raised my hand to challenge the “fact” told to our class that yoga had nothing to do with politics. How could yoga not have anything to do with politics, I asked, when yoga has everything to do with human relationships and freedom? But it just doesn’t, was the only explanation, and the discussion quickly faded.

Modern yoga is very much a part of the global economic system, right down to hyper-consumerism. In the West, particularly the U.S., yoga is advertised as any other consumer product—the message being that happiness is a pair of yoga pants or retreat in Mexico. In India, yoga’s motherland, luxury retreats are taking place alongside extreme poverty, gang rapes, and a lingering caste system.

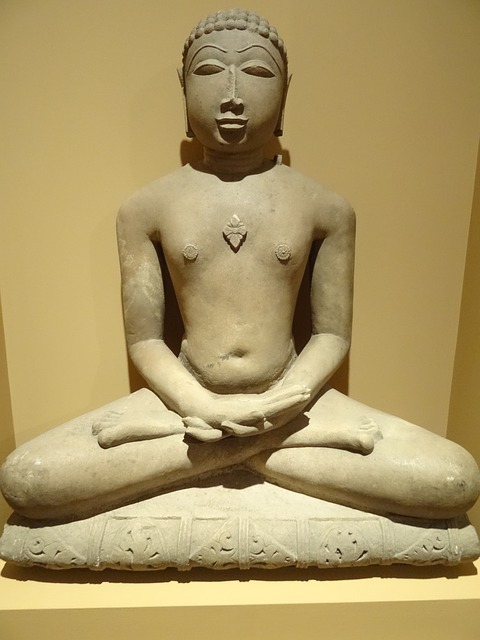

Yoga is a $27 billion-plus industry in the U.S. It includes magazines and manufacturers of yoga mats and accessories—aids that Indian sages did plenty well without when they formulated the science of yoga some 5,000 years ago. Yoga scandals break out from time to time, and they more often than not reflect the same power dynamics found elsewhere in society. The majority of people who practice yoga are women, and several scandals have unsurprisingly involved heterosexual male teachers, trapped in money-and-glory trips, overstepping their bounds.

Yoga can be a highly transformative practice—it certainly changed my life for the better, helping me overcome paralyzing bouts of panic attacks as well as limiting beliefs about myself and the purpose of life. Unfortunately, those who could most benefit from yoga—in terms of building their self-esteem, for instance—can’t access it easily. Yoga studios can’t be found in their economically depressed neighborhoods.

This isn’t to deny the social justice efforts of yoga organizations and teachers genuinely striving to improve lives in conflict zones and gang-filled ghettos. But even some of these initiatives involve high-priced trainings and retreats, keeping social change glued to the current economic system.

This current system of ours generates a lot of fear and judgment—about our own self-worth, how we see people who are in different financial situations than our own, etc.

Everyone has experienced anxiety about wealth in one way or another, regardless of what we hold in our wallets. For some of us, the fear gets expressed as “never enough,” no matter how much, and that can feed questionable ideas about who in our society is a deserving human being. For others of us, it can be scary to speak out against, say, unfairness at work. We worry about risking whatever job security we may have.

Such fears lock us into greed, hatred, paralysis, the undercurrents of conflict.

I find hope in knowing that most of us want to avoid conflict—our human sense of love tells us that peacefulness is the way to live. But we can’t avoid conflict. As individuals, we’ll always tend to see life from our own angles and won’t always agree on how to manage our collective needs. Avoidance is dangerous because it can segue into apathy, an insidious version of disempowerment.

We might even get angry when conflict arises—and it’s best not to avoid that either:. And that is what I’m really aiming for here: anger is a wonderful force for peace and good in the world—if we know how to recognize and work with it.

We’re not bad people if we feel or get angry (so all my yoga and spiritual brethren out there, consider yourself off the hook!). Anger is like any other emotion: there for a reason. Rather than try to pretend we’re not mad, we ought to tune into the emotion to find out what it’s telling us. Borrowing an idea from Professor Michael Nagler, the practice of nonviolent action begins with the conversion of negative energy into a positive force.

People who practice and teach yoga are already familiar with channeling and converting energy, or prana as they say in Sanskrit. This conversion, though, largely prioritizes individual peace over societal fairness. Perhaps that’s because people find it difficult to reconcile individual spirituality with collective politics. It just opens too many cans of worms.

Gandhi sought to transform the whole of society, with freedom from British tyranny in India as the obvious starting point. His ultimate aim was evolving everyday politics so that people could live in true freedom—free from economic oppression, physical violence, the unloving concept of untouchability. Those efforts were spiritual to him because they stemmed from his love for all of life.

Gandhi’s spiritual discipline was in constant dialogue with his political aims, with one never separate from the other. His courage, wit, and perseverance grew out of the same raw, chaotic emotions every human experiences. It was Gandhi’s anger and frustrations at being treated inhumanely in South Africa that sparked his spiritual transformation and his work in nonviolent movement-building.

Inner peace is the very source for shaping a nonviolent world. But the practice of nonviolence, as I’m (re)learning from Metta Center’s fresh perspectives, requires more than finding peace and happiness for ourselves. It requires taking action, even when those actions don’t have cozy results.

While civil resistance has its place and time, there are energy-conversion actions we can take every day that guarantee amazing results, with no jail time required (the options are of course not limited to this list):

- Recognizing and healing our unresolved pains so they don’t interfere with our ability to love ourselves and others

- Showing compassion and empathy for people facing difficulties

- Challenging the widespread belief that we should do more—and faster and better than anyone else—which disrupts our appreciation of the present and fuels unnecessary competition

- Forgoing consuming foods and items produced in ways that harm people, animals, and the planet

- Using our voices to call out injustices

Peace isn’t a gated community in Utopiaville; my peace depends on yours and vice-versa. If I, as your neighbor, were hungry and without food, you wouldn’t feel happy about that. I’m guessing you’d show up at my door with a meal. You would, right?

Thank you for these interesting reflections Kimberlyn. A few years ago I interviewed David Edwards, author of ‘The Compassionate Revolution’ and founder of Media Lens about this topic, with particular reference to the Bodhisattva’s practice of the Six Perfections. You may find the interview illuminating:

http://medialens.org/index.php/current-alert-sp-298539227/cogitations-archive/61-challenging-the-media-from-a-compassionate-perspective.html

Gandhi was once asked this question by a Christian Missionary

What should I do to help the Poor

Gandhi,s reply ::

What we must do is to go and live with the people who are suffering and experience their hardships and their sorrows.

Many times when he had need to go to Delhi he stayed in the Slums with the Poor

PoliticsOfSoul: I look forward to reading your interview—I’ll do that shortly. Sounds like Edwards’s book is one to add to my must-read list.

Garvin Brown: Indeed. As someone whose childhood was mired in poverty, I’ve always found it troublesome when poverty “experts” claim they know what’s going on. Hmm… I think the “experts” thing could show up in the next post… Stay tuned…

Yes, this goes to the heart of our conversation/s. I think part of the problem is people are afraid to hear others views. Many people are on the “same page” without even being aware of it. Awesome article! We all need to help each other, not be afraid to express ourselves..

Debby Bidlack: YES—helping one another communicate lovingly so that we can get past the fears and hang-ups to create a society that works for all is the way to go. I think about labels and how they keep us (I mean people in general) from communicating in productive manners. Example: members of political party A refuse to hear what those from political party B say. And each turns to its own media sources for confirmation of their views. Mainstream media plays a huge role in the divides—most important issues are pegged as overly complex, encouraging people to choose sides rather than cooperate across the board. The media also present just 2 “sides” of any issue, as if no other views or possibilities exist. Who ever said that 2 “sides” is enough to consider? OK, now I want to research that question and see…

P.S. Full disclosure: I’m a former media junkie and journalism student. The whole “objectivity” topic was repeated (and repeated and repeated). But I don’t remember ever learning about where that idea stemmed from (other than appealing to a mass audience). I definitely didn’t learn anything about Peace Journalism, which to “aims to shed light on structural and cultural causes of violence, as they impact upon the lives of people in a conflict arena as part of the explanation for violence.” An interesting read on Wikipedia that’s worth digging into: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peace_journalism