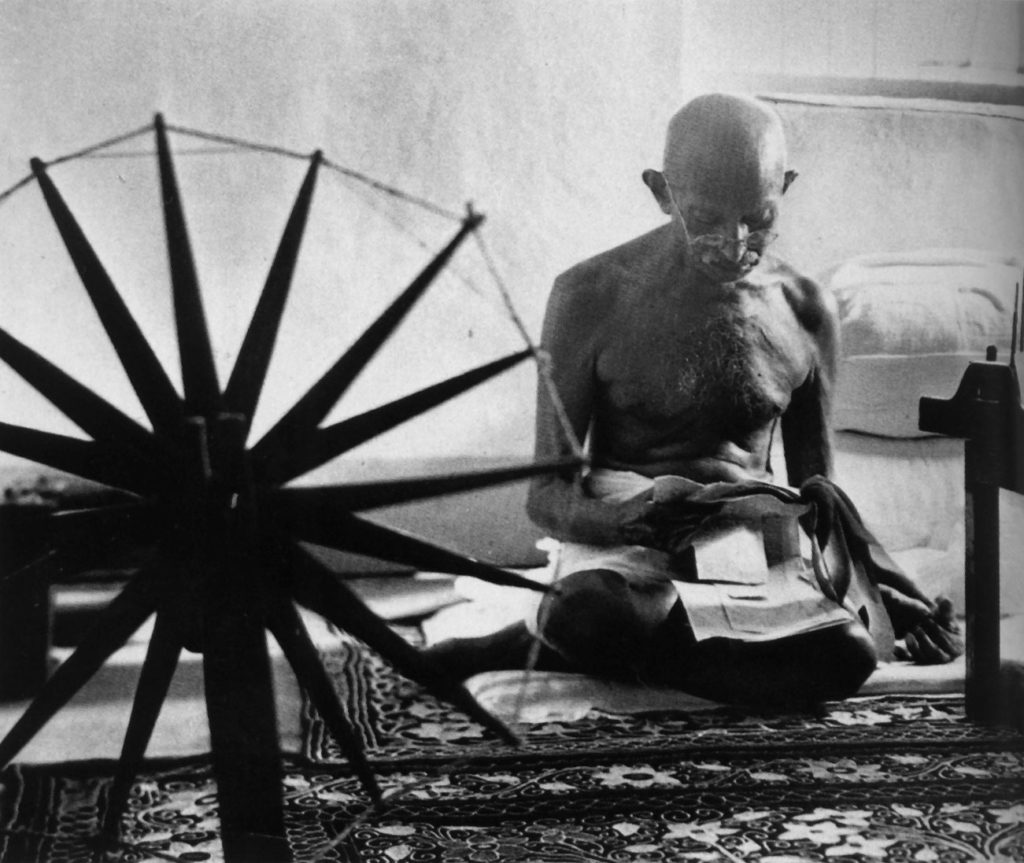

I didn’t learn about Gandhi until I was in graduate school. I joined a Master’s program in Conflict Resolution at Portland State, after spending two years in the United States Peace Corps (Benin 2005-2007). Nothing in my education before then, nothing in my upbringing in the Shenandoah Valley, rural Virginia, mentioned him. When I was in the Peace Corps, someone had left a reproduction of Margaret Bourke-White’s portrait of him on the spinning wheel in my house in a village in rural northern Benin, and I had that on my wall. I recognized him, of course, his stature, his work for peace, but if pressed for any aspect of his life or work, I would have struggled to come up with anything that resembles something accurate about his life or about nonviolence really. I imagine it’s like that for many of us.

Later, as I took up an interest in Gandhi studies, I read around in Joan Bondurant’s “Conquest of Violence,” in various other books that compiled quotes from the Mahatma. I even toyed with the idea of focusing on “Gandhian Philosophy” for my graduate research (which makes me laugh now because Gandhi’s way of life was never a philosophy. It’s a course of deliberate action). It was missing something. I wanted to know about the person, about myself ultimately. I knew he represented that search in some way.

It wasn’t until I began connecting with the work of the Metta Center for Nonviolence that Gandhi took on an even wider dimension. My friends and I began simplifying our lives. We took up meditation. We cut out as much consumerism as we could. We sought more communal structures, more humane ways of engaging with the earth and each other. It came on fast. I wanted to learn and put into practice a form of self-transformation that expressed itself spiritually and politically. If I had been alive in Gandhi’s time, I would have wanted to go to join his experiments in India — I have not the shadow of a doubt!

Michael Nagler told me that something similar happened to him. Gandhi was so far away, so out of reach for someone growing up in Brooklyn, New York. It wasn’t until he met his spiritual teacher, Sri Eknath Easwaran, that Gandhi became “more accessible” and “greater” than he had even imagined. Later, when I worked as a pre-school teacher in a Montessori classroom, I had three to six-year-olds who could describe “civil disobedience” and knew about how Gandhi transformed his anger into power. (I wrote my book “Gandhi Searches for Truth: A Practical Biography for Children,” inspired by those children’s interest in him as they learned about nonviolence from me and my co-teacher.)

What I understand now is that the greatness in Gandhi has to do with what we share in common with him. That he represents for us the capacity that all of us have to examine ourselves in relation to others and the world around us, to examine the quality of our thinking, our capacity for depth into the very heart of matters, while drawing upon a force of life, which he also referred to as Truth, and Love. To think deeply and to act with confidence and conviction when grounded in a higher image of who we are.

On Gandhi’s birthday, Oct. 2, he wanted people in the movement not to make it about him, but about the work of nonviolence. He called it the “spinning wheel birthday,” or Charkha Jayanti. The United Nations has designated it as the International Day of Nonviolence.

I invite you to join us at Metta in the work of nonviolence and upholding Gandhi’s legacy by learning about some of the key concepts and ideals that shaped Gandhi’s life. At Metta, we created a series called “Gandhi for Beginners” — 24 short audio talks that address questions like “What is Satyagraha?” or “What were Gandhi’s rules of fasting?” or “Who were some of Gandhi’s influences.”

Happy Charkha Jayanti.