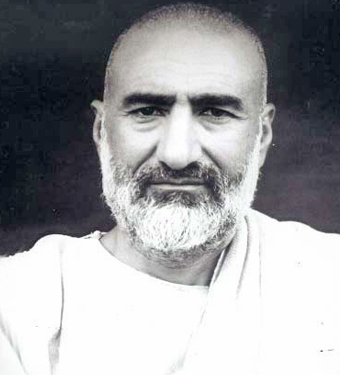

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan came to be known, over his objections, as the “Frontier Gandhi.” (Wikimedia)

If you watched Malala Yousafzai’s much discussed and inspiring speech to the United Nations last week, you may have heard this courageous teenager — who was shot by the Taliban for promoting girls’ education — refer to Badshah Khan as a great inspiration for her determined commitment to nonviolence. You may have also wondered, “Who is this man?” After all, his name is not instantly recognizable like Gandhi or Mother Theresa — the other two luminaries Yousafzai cited.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, later known as Badshah, or King, was born in 1890 in the town of Utmanzai — not far from Peshawar, in what was then the Northwest Frontier Province of India. His father was a khan, or village headman, widely respected for his honesty and more grudgingly, perhaps, for his somewhat independent approach to the Islam of the Mullahs of his day — as well as his coldness toward the code of badal, or revenge, that was a prominent cultural feature among the Pashtuns.

Ghaffar Khan’s early years ran a roughly parallel course to Gandhi’s: He was passionately devoted to the uplift of his people, had a deeply spiritual bent and, at first, accepted British rule as a matter of course, but saw the light when he was deeply offended by certain insults that are the inevitable concomitant of domination. Inevitably, too, his village work, which mostly took the form of establishing schools, put him on a collision course with both the mullahs and the British authorities for similar reasons: educated people are harder to oppress. He came to realize that his educational work, like Gandhi’s constructive program, was “not just service, but rebellion” — a point that must have gone home powerfully with Malala Yousafzai.

The Khudai Khidmatgars or “Servants of God” were the world’s first “army of peace.” (Wikimedia)

Shortly after meeting Gandhi in 1919 — to make a very long story short — Khan founded the Khudai Khidmatgars or “Servants of God” to expand his revolutionary work. Their dedication to him and to nonviolence flummoxed the British, who responded in the only way they knew how at that time: with brutal repression. But Khan was not easily repressed. After perpetrating a terrible massacre in 1930 in Peshawar, the British saw the ranks of the Servants swell from several hundred to 80,000 — an improbable fact if you are not familiar with nonviolent dynamics.

The Servants and their adored leader — who had come to be known, over his objections, as the “Frontier Gandhi” — were shot, tortured, humiliated and (in his case) jailed; but not before they had played a signal role in liberating their country and helping Gandhi give “an ocular demonstration” to the world of the power of nonviolence.

Khan’s incredible life is one of the great untold stories of our time. His “ocular demonstration” went beyond Gandhi’s in evaporating five myths that are commonly held about nonviolence, even today:

- that it is a recourse of the weak: The British never brought the Pashtuns territories under subjection in a hundred years of violence. When Khan once asked Gandhi why his Pashtuns were staying the course when many Hindus lost their nerve and fell back on violence, the Mahatma said, “We Hindus have always been nonviolent, but we haven’t always been brave.”

- that it only works against a ‘polite’ opponent: The British were terrified of and therefore ruthless toward the Pashtuns, whom they regarded as “brutes, to be ruled brutally by brutes.” In the Northwest Frontier, as in Kenya, the empire showed its true colors.

- that it has no place in war: 80,000 uniformed, trained and indomitable Pashtuns were the world’s first “army of peace.”

- that it has no place in Islam: Malala, in his footsteps, pointedly referred to the tradition of peace and nonviolence that is in Islam, as in all world religions.

- that nonviolence means protest and non-cooperation: It includes that wing, but, as with Gandhi’s constructive program, it often gains even more traction with self-reliance, constructive work and “cooperating with good,” where possible.

Yet, outside of Eknath Easwaran’s great biography, Nonviolent Soldier of Islam and a few other resources (including a documentary) there is scant material widely available on Khan and he remains little known in the West. Young Malala Yousafzai may have done the world a greater service than she realizes by honoring his name at the august body of the UN General Assembly.

Posted on July 18 at Waging Nonviolence