August 2:

“I shall deem it ample honor if those who believe in me will be good enough to promote the activities I stand for.”

“I shall deem it ample honor if those who believe in me will be good enough to promote the activities I stand for.”

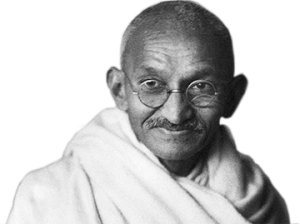

–Gandhi (Harijan, February 11, 1939)

In the 1960s in the United States in particular, “gurus” were the hottest thing on the scene, but since we had not grown up in a culture where the concept was widely understood, there have been many misunderstandings about the work of the guru and misconceptions about what makes a person a guru.

In Sanskrit the term ‘guru’ literally means “heavy,” that is a woman or man so established in their inner security that they need nothing from us, nor can they be ‘pushed out of shape’ by our emotional storms. The guru teaches mainly from personal example, informed by their direct personal experience in the depths of their consciousness, of the supreme reality. They are yukta (cf. ‘yoga’): unified in body, mind, and spirit. The relationship between guru and disciple is the most sacred of all relationships, because it will lead the individual to improve upon all other relationships in their life–how to be a better friend, a more caring partner, a more compassionate neighbor, and more. It is such a sacred relationship that it cannot be taken lightly, nor should it be tossed around indiscriminately. Not just anyone can be a guru for others. Gandhi said, for example, you can learn a lot from a carpenter, being fully aware of their faults, and still walk away a better carpenter. But a guru, as he once explained, is a person who must be free from the shortcomings that compromise our awareness of life’s unity–jealousy, pride, self-deception, denial, greed and the like. For this reason, Gandhi, who was constantly striving to overcome his imperfections (he does state clearly and repeatedly that he is striving for moksha, or self-realization), was never able to accept any one person as his personal, spiritual guru (though he did allow himself the indulgence of a political ‘guru’, G. K. Gokahle). He honored the sages, and testified that their teachings were available to us all even without them being alive; but as for a living guru, he was never able to find the one he could “enshrine in his heart.” Truth, he would say, was his guru, and that teacher lives in the heart of every one of us. We need only (“only”!) turn within to find it.

Still, people insisted that he should be their guru, and he claims to have really felt burdened by this. One man did an entire pilgrimage to visit him, wearing a bronze image of Gandhiji around his neck. When he asked how he could serve him, Gandhi said, “You will oblige me by taking that thing off your neck.” Who can blame those who came to him with such a request, though? He was drawing upon the guru tradition in a very obvious way–establishing ashrams, spiritual communities, which is something that gurus do. Yet, Gandhi said he did not feel worthy of such a title. Worse, it pained him to see people worship with their lips but then do nothing to challenge the system of oppression under which they were living. Hence, if people wanted to honor him, he said that they should look not to him, not build him temples or statues (of which there are many in the world today) but turn all of their energies to the work of nonviolence: freedom, decolonization, nation-building. Paradoxically, for those with devotion to the man, it gave their devotion expression on a new level, and continues to inspire people today who have the same faith in him.

Experiment in Nonviolence:

Take time today to honor the ‘guru’ within you and invite this guru to guide you on the path of nonviolence.