December 10:

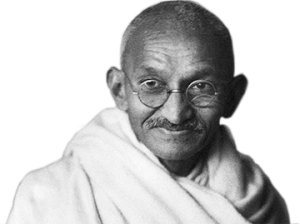

“In placing civil disobedience before constructive work I was wrong and I did not profit by the Himalayan blunder that I had committed.”

“In placing civil disobedience before constructive work I was wrong and I did not profit by the Himalayan blunder that I had committed.”

–Gandhi (Harijan, July 21, 1940)

Freedom is a powerful word. Everyone responds to it on some level. So, whenever we talk about freedom, we have to be clear whether we are talking about freedom to do or be something or freedom from something. Gandhi, it appears, generally thought of the former as a given: we should never consider ourselves not free to do anything that’s right, anything beneficial for ourselves or others. If we are not free to do or be that we have to resist. That’s nonviolence 101. The latter, however, was usually what was at stake in his campaigns: will we be free from poverty, oppression, colonial/corporate rule, violence from ourselves and others, etc?

To this end, we might consider a rule of thumb: whenever we are discussing positive freedom (freedom to) it’s a matter of our rights and duties, and so civil disobedience, obstructive program, as we call it at Metta, is always there as a last resort. Constructive program came to be more important for him as his career unfolded, and finally, as he tells us in the quote, took pride of place. It was and is good practice to act as if we were free to do the needful; if the regime says “you can’t build schools!” or “you can’t harvest your own salt,” they have shown that they’re on the wrong side.

Over the course of his long career, Gandhi learned (he was always learning and evaluating) that the strategic way to combine the two freedoms was to begin with constructive program work and then escalate to obstructive resistance when it became necessary (e.g., when the opponent in question has not responded to the constructive approach). He called it a “Himalayan blunder” to do otherwise, which he discovered, as usual, by experience. Why? Let’s take a concrete example: gun violence. Some people feel that their so-called “freedom” to have a gun is a God-given right, but in reality they are clinging to weapons out of fear. For both these reasons it would be very difficult to force them to relinquish their guns, even though, for example, the problem has reached obscene proportions in the United States. But what if we “softened them up,” i.e. relieved part of their fear first, for example by reducing the general climate of violence that’s taken possession of our culture, mainly through the mass media? Then we could work on the remaining gun owners through more coercive means if we had to, which we doubtless would.

Experiment in Nonviolence:

Where does freedom long to be expressed in your life? What kind of freedom? Consider the constructive resistance approach to address this issue first.