by Metta Blogger and Historian Philip Wight

“The collective power of people working together…that is what will bring about what the world ought to have, which is…peace.”

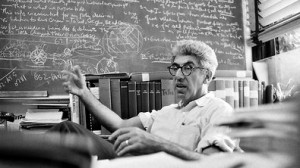

On Sunday the world lost one of the greatest advocates of Ecology: Dr. Barry Commoner. He deserves to be remembered for his pioneering work in the early environmental movement—but Commoner’s dream was for peace on Earth and with Earth. He believed humanity should live for the sake of each other and sustainably with the biosphere.

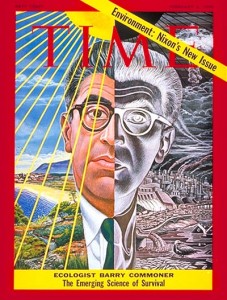

Although trained as a zoologist and biologist, Commoner rose to fame as the “Paul Revere of Ecology.” Commoner was a leading advocate of sustainability, organic farming, recycling, and preventing global warming when many of these ideas were considered radical. His mission to warn Americans of the harmful effects of nuclear bomb testing (which resulted in the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty) and the pervasive presence of toxins earned him the cover February 1970 cover of TIME magazine.

Commoner’s study of Ecology—the “subversive science”—lead him to his most important conclusion: “Everything is connected to everything else.” He understood that a myopic focus on the environment obscured the real issues: social inequality and injustice, war and violence, and the structure of the economy. Commoner’s criticism of free markets earned him enemies, especially in academia and corporate America. Yet the Harvard-trained Biologist asserted, “A scholar’s duty is…not to truth for its own sake, but to truth for societies sake.”

When environmentalists advocated for simple living, Commoner agreed—but warned that as a social solution, thrift was an ineffective tactic. Too many people in the world were starving, even in the United States, and the mantra “consume less” would be laughed at in the ghetto and grape fields. He understood that social justice was a prerequisite for environmental justice; an environmental movement based on affluence and “green consumerism” was destined for failure in a world beset by poverty and hunger.

When the early environmental movement blamed the poor and global South for overpopulation, Commoner offered a pithy retort. Reducing population, Dr. Commoner wrote, was “equivalent to attempting to save a leaking ship by lightening the load and forcing passengers overboard…One is constrained to ask if there isn’t something radically wrong with the ship.” He argued the leaky ship was the economy.

His diagnosis of the world’s social and environmental problems was as simple at it was radical: the “thoughtless way in which we decide what we’re going to produce and how we’re going to produce it.” He argued that the problem and solution were found in the private production system, which unintentionally created pollution, inequality, war, and hunger.

“The current environmental crisis is the unanticipated outcome of the ways in which the corporations that are entrusted with these decisions have chosen to provide us with transportation, food, and power.” To counter these injustices, Commoner believed the economy needed to be reformed to satisfy social needs rather than private profit. He argued for the social control of production that would respect natural laws, produce useful and durable goods, and obviate toxic chemicals and pesticides. “At least in principle,” Commoner wrote, “such a system is socialism.”

To achieve such a system, Commoner argued that only the “collective power of people working together” in the political sphere could forge a more peaceful future. While he said that people must tap into their individual talents and passions to advance this vision, he rejected individual solutions to the environmental crisis. Common admonished, “the hard political path is the only workable route to the soft environmental path.” In the 1980 presidential election, Commoner represented the “Citizens’ Party” and attempted to spark a nationwide debate on the production process and toxic pollution.

Famed health advocate and environmentalist Ralph Nader recently reflected, “Dr. Barry Commoner should be considered the greatest environmentalist of the 20th century. … His great work is reflected in his many campaigns that succeeded and in raising public consciousness to the silent violence of toxic pollution.”

Commoner kept his head raised high and dreamed of a more peaceful future, even as he warned the time to take action was rapidly diminishing. At the age of 90, he declared, “I’m an eternal optimist, and I think eventually people will come around.”

[For more on Commoner’s life and ideas, see historian Michael Egan’s Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival.]