By Kari Risher

Metta Research Fellow

Any human among us can intuitively observe that, as we cooperate with others to serve the needs of our communities rather than ourselves as individuals, we reap social benefits that may not always be quantifiable. As we gain a reputation for being helpful, we are naturally liked and supported by those around us and life becomes richer.

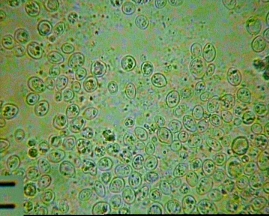

A study published this week in the journal Molecular Systems Biology by MIT’s Hasan Celiker looks at this phenomenon of cooperation on a cellular level, among yeast cells. The study found that, as the ecological system in which the yeast live complexifies by the introduction of other organisms (in this case a bacteria), more yeast cells cooperate by processing sucrose rather than relying on other cells to do it. The researchers hypothesize that the yeast cells have more incentive to become cooperative as competition for resources (bacteria) is introduced because, as they participate in sugar production, they are more likely to have access to the sugar they need for nourishment. They also suggest that, as yeast cells are forced to spread out in a complex environment, it may be more difficult for them to find already processed sugars and thus they are compelled to produce it themselves.