Dear Metta Community,

Black lives matter–because life is sacred in its entirety and its beautiful diversity.

Like all people who have a sense that this is Truth, we are striving as individuals and as an organization to bring this vision to life in our own consciousness, words, and actions. We regard this as the essence of nonviolent change.

In all humility, we invite you to make any suggestions or offer any ideas or support to help us in this effort and on-going commitment.

With heartfelt solidarity,

Michael Nagler, Stephanie Van Hook,

and the Metta Center for Nonviolence’s Board of Directors.

Metta’s Opinion

Maintain Nonviolent Discipline. Be Creative.

Dear Metta Community,

We have heard from many of you. With you, we are in grief in learning of the violent murder of George Floyd and the on-going crisis posed by our criminal justice system especially toward the safety and security of black lives.

It’s especially painful when throughout our Covid-19 pandemic, there have been so many episodes of constructive action and love, of community and bridge building, of mutual support, of glimpsing something powerful and good about human nature in the midst of crisis. We should not lose sight of that in ourselves as we are now confronted with an escalation of an already violent situation that triggers such grief, rage, and anger in so many of us. Those emotions are packed full of power, and yes, they can get out of control and cause destruction in their wake, if we are not careful in maintaining self-discipline.

We must all act from the voice of our own conscience. To that end, we call upon all of the Metta Center’s friends and allies to maintain nonviolent discipline in Thought, Word, and Deed at this time, even more than feels natural or easy to you right now. Nonviolence isn’t easy. But that’s what we all signed up for, isn’t it?

What does this look like?

In Thought: When we find ourselves feeling violent toward another person, we find a way to get space from that person until we know that they (and we) are safe from our own violence. Then, we use our creativity and insight to “put ourselves in their shoes.” What do they really want? What do we have in common?

In Word: Even when it’s hard, we use words that bring healing and show respect as a discipline and training. When we don’t have words that can do that, we use our silence as our words.

In Deed: We refuse to hurt or harm others with our actions. We try our best to maintain this commitment at all costs. We protect others, even at the risk of ourselves and our own comforts if necessary.

Try not to get into ideological arguments about nonviolence right now. We know nonviolence works and have confidence in that assertion. It’s not a surprise that so many people do not understand it, even those who profess to use it, no matter where they are on the political spectrum. Organizations like ours that teach and support nonviolence education are extremely underfunded and undervalued. That doesn’t stop us from doing all that we can, nor should it stop you, as frustrating as it can be sometimes.

This is a time to be sensitive and engaged. Empathize instead. Show people that you care about them and that your caring extends far and wide. Listen to people. You are a force for peace. Know that. Be that. And then, get creative. Protest actions only get us so far and can be easily manipulated by agents provocateurs. We need long-term constructive and creative solutions. Systemic answers to systemic problems. Profound cultural shifts. We need to give our lives to this work, and invite others to do the same through our unflinching commitment. Support nonviolence education.

We care about you. Even though it’s a very challenging time, it’s heartening to think of all of you out there and know that each one of you, in your own way, is seeking to make your own contribution to ending violence in our world. Please, be gentle with yourself and others. Even while being firm and clear.

You’re in this for the long-term. And we’re here for you and with you.

With care,

Stephanie Van Hook, Executive Director

Michael Nagler, President

PS: Michael’s latest book, The Third Harmony, which explores our human nature and capacity for nonviolence, is being generously gifted at 30% off with free shipping from his wonderful B-Corp publisher right now. A great time for a book study or for introducing these ideas to your classroom. Find it here.

Gandhi vs. Coronavirus

I have very little doubt that if I were alive during Gandhi’s time, I would have wanted to be like a Madeleine Slade (or a Herman Kallenbach or Mahadev Desai, or a Sonia Schlessen) and given over my life to be near him, work with him, and join his multifaceted experiments in nonviolence. His wisdom appeals to a severe, almost unquenchable strain of idealism within myself (and I imagine many others), one that is capable of great sacrifice and renunciation and sounds a call to a much higher vision of what the purpose of life is for. And while, to this day, his legacy is fraught and contested, misunderstood and misrepresented — with sifting and patience — there’s always something new and challenging to discover in what we have left of his life in words and actions. For that reason, among many others, I’ve dedicated myself for over a decade now to the work of promoting the power of nonviolence through the vehicle of a small (but mighty) organization, The Metta Center for Nonviolence.

In my work at Metta, I hear from people from around the world. A few days ago, an activist-teacher from Madrid wrote to tell me about a program that he is intending to roll-out online, where people explore how Gandhi might have responded to the Covid-19 political crisis.

Turning to Gandhi at this time is not superfluous. In my shelter-in-place, away from public libraries, I returned to my personal library, and began to re-read Gandhi’s autobiography, “The Story of My Experiments with Truth,” which he wrote in short chapter segments for Young India to be published in a collection in 1927. For those familiar with the book, I need not stress the point too much: Reading Gandhi always provides new insights. The experience is like meeting with a friend with whom one’s relationship continues to grow and deepen. He openly admits it is different from other kinds of autobiographies of his time. Instead of using it to concretize his life, to say “this is me,” he simply wanted to record the series of experiments in truth his life became. In other words, it’s a book of case-studies in personal, constructive, and resistant nonviolence that takes the observer’s self-confessed short-comings and limitations and strivings into account as much as what he observed.

Perhaps due to my own inexperience of the sort, I’m not surprised to find that I somehow overlooked in my previous readings of the book how much of a role plagues and illnesses played in his life as a developing activist, organizer, and self-proclaimed spiritual aspirant. I can’t help but echo the question of my friend in Madrid: Well, what would Gandhi have done during this moment of political opportunity for social transformation? Would he have pushed forward with satyagraha? Would he have defied shelter-in-place? Would he have fasted? (Indeed, yes, he says that during plagues, he felt it necessary to eat less food as a way of conserving his energy for his work.)

I decided to seek out a few people who have been following Gandhi’s life much longer than I have, and who, as it turns out, have been asking themselves the same question: When it comes to Gandhi vs. the coronavirus, what would he have done?

—

My guess, for whatever it is worth, is as follows: 1. He would think of the neediest and most vulnerable among us, including the front-line carers, and strive to assist them. 2. He would observe that, cleaning our spectacles and removing the mist from our eyes, the virus has restored the reality of death. It has enabled us to realize afresh the value of life — of loved ones, clean air, human life, non-human life. Helped us to not take our being alive, or our loved ones being alive, for granted. 3. He would underline the virus’s reminder of the equal vulnerability, and thus the equality, of all races and nations. 4. He would use the virus, and the solitude obliged by it, to identify our shortcomings as communities.

– Rajmohan Gandhi, grandson of M.K. Gandhi, and author of Why Gandhi Still Matters: An Appraisal of the Mahatma’s Legacy

—

While I believe Gandhi would be right in the front lines risking his life to help the worst afflicted, I firmly believe in his vision (and many others) that there is a tremendous positive force within the human beings that the most degraded circumstances can never abolish: “The fact that [hu]mankind persists,” he once argued, “shows that the cohesive force is greater than the disruptive force.” No matter how much evil we see around us, how much lying, truth has an undying appeal with untapped power — including the truth that life is sacred and interconnected everywhere. Why else would three thousand students and young people volunteer to be infected with Covid-19 to test out an experimental vaccine?

– Michael Nagler, professor emeritus UC Berkeley, author of The Third Harmony: Nonviolence and the New Story of Human Nature

—

In the current dire situation, Gandhi would emphasize health, hygiene, and homegrown goods, as well as a concerted and compassionate response to the virus as he himself led during the spread of black plague in South Africa. He would call on us to return to the moral values of ahimsa (nonviolence), satya (truth), and swadeshi (one’s own region; self-sufficiency).

Coronavirus has revealed both the strengths and perils of our globalized world. Gandhi’s principles can help us confront the fear that can shut us into our silos: “I do not want my house to be walled in all sides, and my windows to be closed. Instead I want cultures of all lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet.” We must realize the air is life giving, and is shared by all equally, irrespective of age, status, gender, religion, etc. The concept of sarvodaya (uplift of all) must be the guide: all beings are connected in both biological and spiritual ways.

– Veena Howard, professor of philosophy at Cal State, Fresno, and author of Gandhi’s Ascetic Activism: Renunciation and Social Action

—

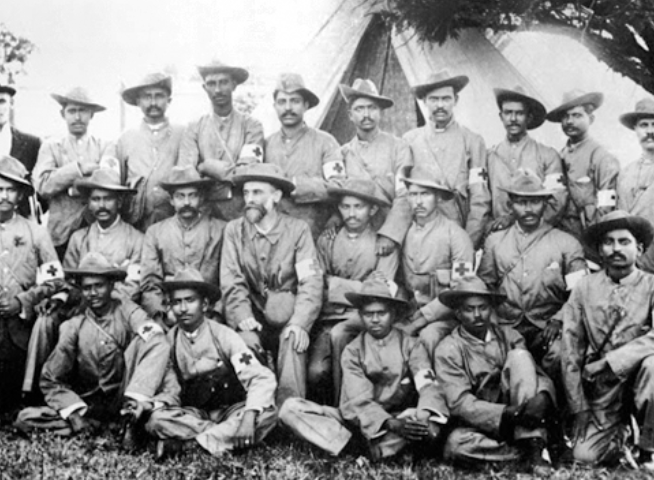

At this time of the coronavirus pandemic, when health care practitioners are being celebrated the world over as “front line” workers who have put their lives at risk, it is worth recalling that Mohandas Gandhi was something of a trained nurse. It is commonly thought that he first started nursing the sick and the wounded when he set up an Indian Ambulance Corps, consisting of 1,100 volunteers, during the Boer War in South Africa in 1899. However, as his autobiography makes amply clear, it is on his visit to India from South Africa in the second half of 1896 that he was able to nurture his instinct for nursing which had first manifested itself when in his adolescence he looked after his ailing father. The Bombay to which Gandhi returned was being decimated by bubonic plague, and he found himself spending day and night by the bedside of his brother-in-law, who had taken seriously ill and whose wife, that is Gandhi’s sister, “was not equal to nursing him.” Gandhi could not save his life; however, as he was to write, “my aptitude for nursing gradually developed into a passion, so much so that it often led me to neglect my work, and on occasions I engaged not only my wife but the whole household in such service.”

So what might Gandhi have thought of the present pandemic, the jeopardy in which the livelihood of tens of millions of people around the world has been placed, the enormous toll it has taken of human lives, and even, considering his own stated “passion” for nursing, of the advice of scientists and doctors that each one of us should practice “social distancing?” Gandhi held to the view that there are laws of compensation at work in this universe, however opaque they may be to us, and I suspect that, to take one illustration, the comparatively clean air in the wake of the shuttering of the world economy would have been construed by him as a sign to human beings that we should be mindful of the devastation we have wrought upon the earth. But Gandhi was not one only to philosophize: It is impossible to imagine him not present on the scene, tending to the sick and comforting members of their families. Yet, though his compassion was boundless, Gandhi was also tough as nails, and I suspect that he would have punished himself to the hilt in working around the clock, organizing relief workers and cajoling people not to rely on government handouts but to make themselves useful and apply their ingenuity. His relentless critique of industrial modernity has led many people into believing that Gandhi was opposed to science, but that is far from being the case: He was a scientist in his own fashion, ceaselessly testing the truth of every proposition, but, more critically, he was opposed to scientism. While he would have respected scientific advice, I think it can safely be said that Gandhi would have also said that we cannot leave our understanding of the pandemic and its social, political, and philosophical implications to the scientists alone, because the pandemonium engendered by the pandemic is ultimately a reflection of the unrest within each of us and within homo sapiens as a whole.

– Vinay Lal, professor of History, UCLA, (see his webcast on the Moral and Political Thought of Mohandas Gandhi in its entirety here).

—

And now, what about you?

When we turn to Gandhi as any historical figure of nonviolence, it’s about turning back to ourselves: What we are willing to do, what kinds of renunciations we are willing to make, how do we define and expand our sense of community, and how we can move forward with the needed lessons of this chaotic time in a regenerative, life-affirming, and strategic manner?

I invite you to return to Gandhi with me, to re-read his writings, to ask questions and to take meaningful action. To support you, every Friday, the Metta Center is hosting a Hope Tank — an open, but focused, conversation about nonviolence — and you are most welcome to join us.

Learning to Let Go

This is a guest post from volunteer, Astrid Montuclard, after attending our weekly Hope Tank. Find out more about Hope Tank at this link.

“What are you learning to let go of amidst the pandemic?” Bathed in my computer’s silvery light, my heart shivers to the question. For six seconds, the words bounce around the Zoom room of the Metta Center for Nonviolence’s virtual Hope Tank. She-who-knows-everything comes to my mind. How safe she feels… she has answers to heartbreaks, shortages of toilet paper, suspect coughs, procrastination, and longing for hugs. In these times, she is the best friend of those seeking for guidance outside of themselves.

She-who-knows-everything, when scared, likes to emerge from the depths of my soul. Yet, she is not the facet of myself that I wish to offer amidst the crisis. I am vigilant to love her – and yet to also lie her to rest as much as necessary. For she does not always know to listen from the heart. She does not know to sustain silence for the additional second necessary for two gazes to catch a glimpse of their vulnerability. She does not know to let her body tremble when the news shout that thousands of people died today. She does not know to cry in front of those she loves. She does not know to embrace the full spectrum of human emotions with kindness. She only knows to paint her and others’ minds with Old Stories of strength, control, and composure.

But these days, I am learning to let go of her – she who believes to have an explanation, an answer, a solution, and a decision available when not-knowing and ambivalence fill her ribcage and the eyes of those around her. These days, I am learning to let go of avoidance and embrace the painful reality that I, too, do not always know how to respond to Change.

When she-who-knows-everything melts away, and I do not find words to comfort my friends who are scared because they lost their jobs, I smile painfully and convey through my gaze that “I am here with and for you – and I accept that is all I can do right now.”

When she-who-knows-everything melts away, and I do not find resilience to keep my composure as conflicts explode around me, I remind myself that being gentle in picking up the broken pieces of my ego is sometimes the only thing to do while waiting for the storm to pass.

When she-who-knows-everything melts away, and I cannot deny anymore the fear strangling my lungs while turning in bed at night, I put on music in my ears and let my body feel fully its own humanity, until sleep washes away the running stream of my thoughts.

When she-who-knows-everything melts away, and I can finally face that we will not be the same again after Covid-19, I try to sit quietly and listen with my spirit and soul for the quiet steps of slower mornings already on their way.

Yes, these days, I am learning to stop resisting and sit in the peaceful fire of feeling time flow through my body without direction. As I was sitting in the sun this afternoon, a feeling of expansiveness came upon me. She-who-knows-everything got it… There is rest in not-knowing. There is rest in not-knowing, when suddenly the need to think for answers or repeat aloud thoughts whispering the “right thing to do” disappears. When suddenly, sitting lovingly with myself and others, just as we are, becomes the right thing to do – and the New Story to embrace.

Yes, there really is peace in not-knowing. And these days, I need that peace. It is fertile with new possibilities. I can let go of the belief that I must be perfect for everyone all the time – finally.

Finally, I can rejoice in truly not knowing. And it feels like the Earth herself approves.

From Metta Mandir: Part 2

From Metta Mandir: Part 2

Last time we touched on what can be considered the most important single action an individual — any individual — can take to begin to restore a sane direction to our culture, which we regard, in turn, as the most important project to restore a sane direction to humanity. We can read more details on how our media went off the rails in The Third Harmony; one aspect not touched on there is what one journalist has called the “journalism of deference” in which the White House and the military control the presentation of war-related news, creating, in other words, the ‘military-industrial, media and entertainment complex.’

Here, for a breath of fresh air, let’s look into Step Two:

“Learn all you can about nonviolence.”

On the psychological level any positive news will help us, as common sense, personal experience, and a lot of science confirm; but we believe that news about nonviolence — and anything we can learn about nonviolence, is particularly effective, since we regard nonviolence as the most positive thing that can be said about the human being, and about our possibilities in this world.

Raising this consciousness is precisely Metta’s project, of course, which we try to carry out with all our projects that are aimed both at the level of particulars and their overall meaning for our culture and life, in other words, facts about nonviolence itself and efforts to build a culture based on that principle. Accordingly, we suggest that people go to our website, books, courses, etc. as our default recommendation for anyone who wants to begin or deepen their journey to that discovery.

When Metta was born (in 1981) you could read just about everything available on the subject of nonviolence, leaving aside Gandhi’s enormous contribution, in a few years. Now it would take a few lifetimes. Academic programs were nearly nonexistent; now there are several within the peace studies fold that do a creditable job on nonviolence, like the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford and the Endowed Chair in Resistance Studies at UMass, Amherst held by our good friend Prof. Stellan Vinthagen. (Since there is virtually no funding in post-secondary education for anything outside science and technology an endowed chair, which I tried in vain to establish at Berkeley, is about the only way to open the field).

Outside the universities, we have free-standing institutes like the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict in Washington, DC and specifically nonviolence-oriented non-profits like Metta: Nonviolence International, The Resource Center for Nonviolence in Santa Cruz, the MK Gandhi Center for Nonviolence in Rochester, and others.

All these resources are useful in themselves, and most useful as preparations for the best learning tool: our own experiences. Nonviolence begins within us (the ‘third harmony’) and can express itself in almost any situation on any scale from one-on-one interactions to global politics.

We have an unfailing “library” of experiences to learn from, then, once we know what to look for. For example, we don’t just look at immediate, tangible results but also for processes going on under the surface that may show up far down the road, not infrequently in better results than we were aiming at.

At Metta we call this “work” vs. work, and the classic example is Gandhi’s salt campaign of 1930 which actually achieved very little in terms of relief from the oppressive salt laws but which many recognize as the end of British colonial rule that was formalized 17 years later. Spot some of your own! It’s a lot of fun.

From Metta Mandir: Part 1

From Metta Mandir: Part 1

At a recent virtual hope tank dedicated to finding positive responses to the “shelter in place” order here in California and elsewhere we realized that Gandhi did some of his best writing — and meditating — in the jail that he renamed “Yeravda Mandir,” or temple.

There are parts of the Bhagavad Gita that I take literally, and among them two verses from Ch. Four stand out at any time, but particularly one like this:

“Whenever dharma declines, and unrighteousness swells forth, I incarnate myself from age to age . . .”

If there was ever a time that fits this description, when human degradation menacingly raises its ugly head, it’s this one. Where, then, is our incarnation?

I can imagine the Supreme Being answering, “What did you do with the last one?”

Or perhaps s/he is yet to come; or perhaps, and this is the safest interpretation, we are (to be) that incarnation, that saving power.

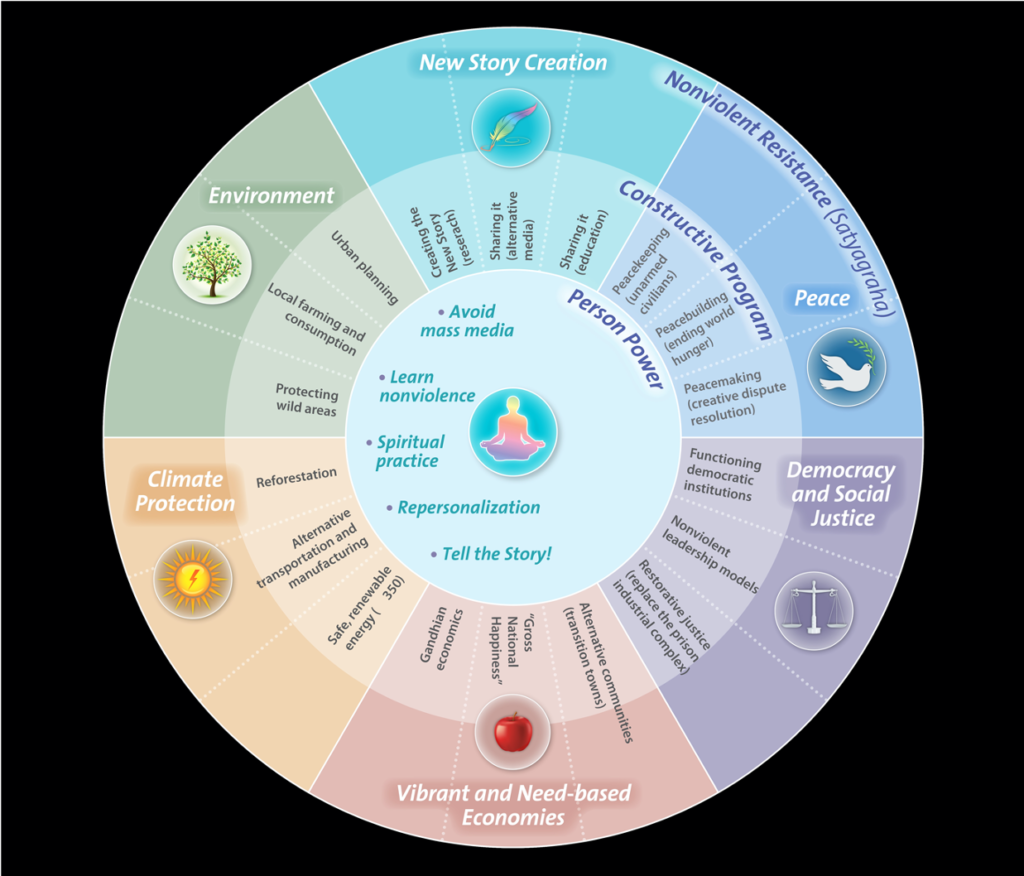

Our response, in addition to everything else we’re doing, is to lift up the five points for Personal Empowerment embedded in the core of our Roadmap.

They deserve some elaboration, and accordingly, we decided to follow up on our recent article in Waging Nonviolence, which introduces Roadmap in general, with five pieces over the next five weeks dedicated to each of the five points in turn.

Point Number One: Use extreme caution with violent and degrading media.

How pertinent, when so many of us are “sheltering in place,” our kids out of school, desperate for wholesome entertainment on the one hand and of course glued to the news! A hard time to tell people to back away from the media.

Yet, when you develop some sensitivity to what a human being really is and some skill in reading the “subtext” in an advertisement or a piece of “entertainment,” you begin to realize that there’s very little left in the commercial world of media that does not in fact trivialize, misrepresent and degrade us.

It does not have to be an action movie or an ad message like “Our pain is your gain” (seen on a recent Petaluma billboard) to try to tell us we’re small-minded, competitive fragments caught in a nexus of violence.

So, one objection this suggestion meets with is, ‘There’ll be nothing left to watch.’ Point number two in the inner circle, and all of them in their own way answer this objection.

The next one is, ‘How will I know what’s going on in the world if even the news is slanted toward violence and firmly embedded in the Old Story (which it is)? Fortunately, there are more and more resources now to fill that gap; the field is expanding so rapidly that even the Appendix to my new book, The Third Harmony will soon be out of date!

Don’t let anyone tell you that they “like” violence, and it doesn’t do any harm. There are thousands of studies proving that watching violence makes us more violent in attitude and eventually behavior, and a growing awareness that while we may have been so far conditioned that we get a rush of some kind seeing it, violence alienates us and sickens the mind.

It’s a part of what the military calls “moral injury” (and tries to ignore). While breaking an entrenched media habit is unquestionably going to be a struggle for many of us, it really doesn’t take long for our sensitivity to return so that we enjoy peace of mind, and not at all its disturbance.

Go at your own pace: a periodic “cleanse,” cold turkey, a gradual reduction to just about zero — whatever works for you. The benefits are their own reward; who wants to be conditioned, really — to anything.

May there be harmony…

Emergencies can be times of emergence…

I’ve been thinking, writing, and consulting with individuals and movements about the power of nonviolence for many decades, and I’ve never seen a time when it was more needed. Why do I say this? Because times of chaos and confusion are also times of fierce caring and connection. Emergencies can be times of emergence. As I argued in my recent article in Waging Nonviolence, times of upheaval are when nonviolence can express its full force; often, if we are prepared, the real mirror of our human nature appears (and it’s not violence!).

(more…)‘The Un-Shock Doctrine’ — or why we need a plan to rebuild

In times of uncertainy and turmoil, the only way to rebuild — rather than regress — is to have an alternative strategic plan.

They had set the bar pretty high. The science students around the world who wanted to enter the contest to see whose rubber-band powered airplane would fly furthest saw that even to qualify their model had to fly 30 yards. But some of them made it. In particular, the Chinese students: Their entry was in a class by itself, and flew way further than the nearest competitor. What was their secret? A translation error. They thought to qualify it had to go 300 feet — or more than three times further. We are now challenged to come up with the same daring and imagination; only the stakes are a lot higher than a model plane contest.

Many of us are familiar with Naomi Klein’s 2007 book, “The Shock Doctrine,” in which she describes with devastating accuracy how regressive forces systematically exploit — and even create in order to exploit — times of uncertainty and upheaval to press their cynical agendas. There is a lot of fear that the pandemic now upon us, the mother of all upheavals, will be used for just that purpose. In fact, it’s happening: Think of the trillion-dollar bailout the president wants to offer fossil fuel industries! The fear is not unjustified. But it is not the whole story. Times of upheaval and turmoil are also times of possibility.

What makes all the difference, what makes it possible in such a time to rebuild rather than regress, is an alternative plan. In her recent interview with Amy Goodman, Klein, quoting Milton Friedman (of all people), said that at times like these opportunities open up for “whatever ideas are around.” And she goes on to list some of the excellent ideas that have been around, in some cases, for quite a while: a Green New Deal, healthcare for all, decarceration, forgiving student debt, etc. But that’s just the problem: They’ve been around for quite a while without gaining traction, and in the presence of so many bad ideas with untold resources behind them, there’s no guarantee that they will prevail now — that the opportunity presented by this fluidity can be seized on by those of us who want a new day.

“Apathy can only be overcome by enthusiasm,” said the famed British historian Arnold Toynbee. “And for enthusiasm you need two things: an idea that takes the imagination by storm and a concrete, practicable plan for putting that idea into action.”

We’ve already got that idea, if we know where to look. Jonathan Cook pointed to it in an article published by Common Dreams. Among the lessons the virus can teach us (assuming we’re prepared to learn) is that: “In a globalized world our lives are so intertwined that the idea of viewing ourselves as islands — whether as individuals, communities, nations, or a uniquely privileged species — should be understood as evidence of false consciousness.” Cook further explained by saying, “In truth, we were always bound together, part of a miraculous web of life on our planet and, beyond … in an unfathomably large and complex universe.” There’s no problem identifying the wrong consciousness: a “political worldview … so obscenely stunted by the worship of wealth that it refuses to acknowledge the communal good, to respect the common wealth of a healthy society.” I want to emphasize the terms “worldview” and “false consciousness,” because that’s what we really need: a truer consciousness, one that underlies and is a common foundation for the political or economic fixes listed off, quite correctly, by Klein.

We need the worldview that’s always been there, but is mostly buried in what are called the world’s wisdom traditions — and that have now, for the first time in over 300 years, the solid backing of science. The core of this worldview for our purposes is its strikingly different image of who we are as human beings. We are not primarily separate bodies, as advertisers and others try incessantly to tell us. We are body, mind, and spirit, or consciousness — indeed primarily consciousness. And that has tremendous consequences. It means we have untold resources within us, and we are deeply interconnected in a single web of life or what Martin Luther King called a “single garment of destiny.” It means that the life we have been given to live — and the universe we’ve been given to live it in — are not the result of random forces. They are deeply endowed with meaning that, in principle, we can discover, and according to which we should live.

This idea both pulls into a single focus and provides a conceptual framework for the many components of a progressive agenda that have been proposed but not adopted, and can help them get adopted. It has been identified and worked out in some detail by a long line of distinguished thinkers, including — in our own age — a line that goes from Teilhard to Einstein and, conspicuously, Gandhi. Yet, despite the prominence of these thinkers, and the increasing support of modern science, this worldview cannot be said to enjoy much currency in public discourse. Hence the need, as Toynbee pointed out, for a “concrete, practicable plan” to get it realized. And that plan, as I see it, will have three parts.

The first part needs to be a manifesto that boldly lays out the world we want. This might be something like the 500 Year Plan for Peace that was put forth by the Sarvodaya Movement in Sri Lanka. Although the movement has faltered, to be sure, the plan is still inspiring.

The second part should be a very carefully thought out strategy for moving people to implement the plan. Fortunately, in the last 20 years or so peace and justice movements have been systematically collecting and analyzing their “best practices,” ranging from insurrectionary movements like the one that overthrew Slobodan Milošević in Serbia in 2000 to the work of Nonviolent Peaceforce and other groups that carry out what’s called Unarmed Civilian Peacekeeping. (As I write this, Nonviolence Peaceforce is concluding an ambitious series of global gatherings for this very purpose). Thanks to strategists who have been in this business for some time now — like Daniel Hunter and George Lakey to name just two — the futility of one-off protests and the value of starting with the “low hanging fruit” of achievable goals and advancing steadily toward far-reaching change are getting to be common knowledge among activists.

Finally, part three, we need a way to organize people to make this happen.

I may be in a position to offer at least a framework for all this. At the Metta Center we’ve been working for some time now with what we call a Roadmap that gives visual expression to the potential unity of our emerging movement. For convenience, it divides the issue areas to work on into six sectors. They are, as I say, for convenience and not to be taken as rigid boundaries. But there is one thing we regard as essential: the sector called “New Story Creation.” This is the work, formulating and promoting the new paradigm, that must be front and center if we’re to have the kind of new consciousness Cook describes. At the least it should accompany everything else we’re doing. Roadmap has two other features of interest: It lays great emphasis on what Gandhi called Constructive Program, building the new world, piece by piece, without waiting for the powers that be to give it to us. What’s more, it fits it into a kind of centrifugal trajectory from Personal Empowerment to Constructive Program and finally to Direct Resistance where that’s still needed. This is a natural progression for a successful movement.

Many parts of what could become our constructive program are already happening more or less spontaneously in response to the crisis. People are growing their own food, shifting from schools to homeschooling, from hospital births to home births. Here and there prisoners are being seen more compassionately and getting released from prisons. People are trying to figure out how to make their own things — and helping their neighbors in this and other ways. In some cases (despite the proposed stimulus giveaway), a Canadian friend tells me that even oil companies are putting off their projects. Meanwhile, another friend points out that “sheltering in place,” now affecting about a fifth of this country, could be a blessing in disguise. Didn’t Gandhi welcome jail time as a badly needed opportunity for reflection and serious spiritual practice? The heart and soul, after all, of Personal Empowerment.

There’s a big picture hovering behind these spontaneous activities. That picture can pull them all together, give them a local habitation and a name, and rough out a strategic plan for implementing them. We will never say we were glad the pandemic happened, but if we can pull this off we’ll be able to say that all the suffering was not entirely in vain.