There was a time years ago when I was reading Plato very closely – I was studying at Heidelberg at that time – and had a flash of insight about who Socrates really was. What I saw was not something I could easily share with my fellow students, then or now: that both Socrates and Jesus were at bottom not so much philosophers or avatars or whatever we want to call them: they were human beings who cared passionately for our welfare. A poignant observation, to be sure, given the way the societies of their time, respectively Greek and Roman, treated them. At the time, however, I was not thinking about that sad comment on humanity’s folly but almost basking in the intense loving concern I felt coming from both these distant figures. That vast compassion, that desire to uplift and help us, was not just a mission for them: it was what they were.

There was a time years ago when I was reading Plato very closely – I was studying at Heidelberg at that time – and had a flash of insight about who Socrates really was. What I saw was not something I could easily share with my fellow students, then or now: that both Socrates and Jesus were at bottom not so much philosophers or avatars or whatever we want to call them: they were human beings who cared passionately for our welfare. A poignant observation, to be sure, given the way the societies of their time, respectively Greek and Roman, treated them. At the time, however, I was not thinking about that sad comment on humanity’s folly but almost basking in the intense loving concern I felt coming from both these distant figures. That vast compassion, that desire to uplift and help us, was not just a mission for them: it was what they were.

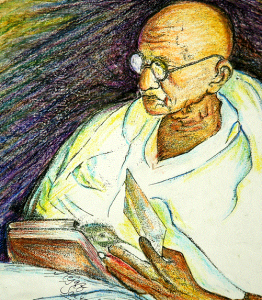

Though I never developed or even shared this insight very much over the years, it stayed with me, and came to life when I heard, some time later, the intriguing phrase Gandhi used to explain the hold that the Bhagavad Gita had over him: this was not a text, it was his “mother.” It’s hard to imagine a more vivid image to convey the benefit we stand to receive from that repository of such wisdom, and the love and awe we begin to feel for the immense spirit that lies behind it.

Whoever composed the Gita (tradition ascribes it to a sage called Vyasa) he or she or they pulled into a single, accessible focus a wisdom developed over thousands of years of continuous tradition, where there seems never to have been a time when the lineage was broken – when there was no one alive who had realized the goal of life and added his or her own voice to the “Song of the Lord” (the literal translation of bhagavad gīta), burning to share the intense joy of the experience with all who would listen. If it were only for its immense value to Gandhi and what he delivered to the world (or delivered the world from), the Gita would be inestimable. But there’s the additional fact that with a little training, a little familiarity with language and ideas, anyone can drink at this same source. Who would not identify with Arjuna, the anguished warrior whose whole life has pushed him into a battle he no longer wants to fight? “Stand up,” Sri Krishna exhorts him: “think of your honor. Fight this battle you have been waiting for” – the battle, that is, against every inhibition, every destructive impulse in his mind. His questions are so much our own: “Krishna, Krishna, why do I do these things I know are wrong?” and “What happens to me if I give up the worldly life and still can’t make it to the spiritual goal: do I lose everything?” And who would not drink in the reassurance of Krishna’s firm answer: “Dear one, there are no ill effects of this struggle, there is no backsliding. No right effort will be wasted, no harm can come to a good person, either in this life or the life to come.”

Anyone would thrill to these words, especially those who could hear as I did Socrates’s final exhortation to the Athenians who had just condemned him to death, a speech I had memorized years before: “But you also should take heed, my fellow citizens: the gods are not oblivious to these matters, and no harm can come to a good person whether in this life or in the life to come.”

Nice post! The Gita is also one of my favourite scriptures and certainly the one I have read the most. Gandhi’s comment that the second chapter (on actionless action) is the essence of it, that the Gita ends at chapter 2 and that the rest is commentary quite striking when I first read it! I am not quite sure if I would agree but certainly the second chapter is immensely inspiring.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, in various places, wrote about Plato and the Gita saying very similar things about human nature and vocation. Those writings of his too are very inspiring I think.