October 19:

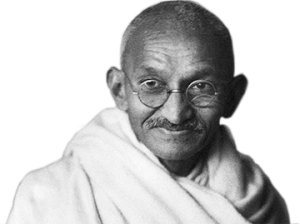

“The prayers of peace-lovers cannot go in vain.”

“The prayers of peace-lovers cannot go in vain.”

–Gandhi (Harijan, February 24, 1946)

Public prayer can be a powerful form of nonviolent action when used with discernment within a broader nonviolent strategy. One of Gandhi’s first calls to action in India, for instance, was a hartal, or ‘strike’, but in his interpretation a national day for prayer and fasting. For that kind of penance to take place, of course, work was called off for that day, transportation slowed, the economy took a hit. Fast forward to the African-American freedom struggle in the 1960s when a group of picketers saw the police coming toward them with dogs and water hoses, and instead of advancing, they sat down and prayed together. Not rare occurrence in either struggle, and not to mention that the Civil Rights movement organizing took place in churches. Or remember Father Kolbe in Auschwitz, dying in the place of another prisoner and ministering to those who were condemned to die with him. Fast forward to Argentina when the famous “Madres de la Plaza de Mayo” would sit in the pews, praying, while also passing notes between themselves about their movement’s actions. Look over to the Philippines People Power revolution, where you have Catholic nuns praying before armed soldiers; or go across the world to Liberia when Women for Peace organized Christian and Muslim women to come together to end a decades-long civil war. Then there was the Egyptian revolution where we saw Muslims praying while soldiers looked on, unsure of how to proceed. Or the Indigenous struggles against pipelines, fracking and tar sands, often including prayer ceremonies. Or the “meditation flash mobs” on Wall Street.

Creative resistance. None of it has gone in vain.