IN AUGUST OF 1932, MAHATMA GANDHI WAS IN PRISON WHEN NEWS REACHED him that the “Paramount Power,” the British Raj, planned to introduce separate electorates for the untouchables and the caste Hindus. Believing that this would amount to a “vivisection” of India, what was he to do? On September 13th he stunned the nation by announcing that he would embark on a fast unto death the following week until the hateful measure was withdrawn. The “epic fast,” as it came to be called, succeeded brilliantly, but it had come close to costing him his life. To those who asked what had possessed him to do it, Gandhi calmly replied that he had heard the voice of God. Even in India, there were those who said that Gandhi was hallucinating. But he said:

The claim that I have made is neither extraordinary nor exclusive. God will rule the lives of all those who have surrendered themselves without reservation to him. Here is no question of hallucination. I have stated a simple, scientific law which can be verified by anyone who will undertake the necessary preparations, which are again incredibly simple to understand and easy enough to practice where there is determination.

Striking—and most pertinent to issues raised by Tikkun and the NSP—is that he was able to marry good scientific logic with what seems to most of us a transcendent religious experience. How did he do that?

In the beginning of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad, an important Vedantic text, we are told that in the depths of their meditation sages saw devatmasakti, felicitously translated as “the God of religion (Skt:deva), the Self of philosophy (Skt: atman), and the energy of science (Skt: sakti)” In their vision of the Supreme Reality, science, philosophy, and religion were one—somewhat like the Christian Trinity. And with this vision, Indian science reached great heights. It is fairly well known that Indian philosophy was in a class by itself; it is much less well known that until the seventeenth century, India’s astronomy, medicine, and other sciences were at least on a par with comparable sciences in the West. It was only with the rise of colonialism, along with the rise of ‘rationalism’ and materialism in Europe, that the sciences of what became the Third World were pushed into the background.

But that was then. Now the great breakthroughs of Einstein and Bohr have delivered a rude shock to the paradigm of Western science, and “only Vedanta,” as a prominent Indian physicist who joined religious orders as Swami Jitatmananda said in 1986, “seems to be in a position to absorb the tremendous impact of the new science.” The Vedanta—a general term for the spiritual culture of ancient India—developed a quantum theory of mind 5,000 years before Planck discovered that energy comes in discrete packets (or quanta). It even came close, perhaps as close as words can, to accounting for the fundamental mystery of modern physics: how the strange quantum world of infinite potentialities becomes the “concrete” world of our ordinary experience; or in broader terms how the unchanging, infinite Reality becomes or in any way interacts with the flux of spacetime in which we live (the concept I’m thinking of, of course, is maya, Sanskirt for “illusion,” although this fails to describe the full complexity of the word).

Gandhi was able to marry science and religion because for him they had never been divorced.

This is an attractive vision. It could even have a strategic value for the revolution that progressives, especially Tikkun-reading spiritual progressives, yearn for. Despite the frightening rise of fundamentalism in the modern world it remains true, as Willis Harman used to say that, “Science is the knowledge-validating system of our civilization.” For most reasonable people (and admittedly their number is shrinking), something can be true only if it can pass the test of science; e.g. if it is universal and verifiable in the sense Gandhi claims for his experience of God. However, we of the “reality-based community,” in the sarcastic words of a Bush aide, are losing ground to those for whom science as we know it is at odds with “religion” as they know it. This means that often, for a conservative, some things can be scientifically valid or moral, but not both. Note how the President’s cavalier disregard of science (not to mention truth), i.e. in the area of stem-cell research, has started to make his position increasingly ludicrous in some quarters.

Peace researcher Kenneth Boulding explains, and every activist intuitively recognizes, that legitimacy is a key to the preservation or overthrow of any regime. Take away the legitimacy from a totalitarianism, for example, and it is all but gone. This is how nonviolent campaigns work, how they may yet be working in Burma today. The pitting of science against religion in the prevailing neoconservative regime has actually put a small crack in the sources of its legitimacy, and hence its power. And this has occurred concurrently with quite a few recent developments in science that have been not just compatible with, but supportive of, the vision of human beings as empathic, free to determine their destiny (not ruled by genes or hormones), and deeply interconnected on the spiritual level.

We progressives are not wedded to a narrowly moralistic definition of religion or an exclusively materialistic, externally-oriented definition of science. We can have a mature religious sensibility that has nothing to fear from the findings of real science, a complete inquiring system in which, as the Dalai Lama has been arguing, religion deals with the subjective and science the objective dimensions of existence. The Vedanta was such a system.

But how available is a system that emerged from the soil of ancient India for contemporary and Western people? This is why I have been stressing the scientific nature of Gandhi’s approach. As he once said, “To be a Hindu you have to be born into a Hindu family; but it is open to anyone to practice Hinduism.” I’m a pretty good example, since in the course of my life I went from being a non-practicing Jew to a practicing non-Hindu, i.e. practicing meditation while not, for the most part, observing the many rites or celebrations, the karmas (mitzvot) of modern Hindu worship. In my personal experience the Vedantic worldview has been literally a godsend; I find it without equal in my ongoing struggle to understand what life is about and what I’m supposed to be doing here. That is because it is more than a worldview. It cannot be taken apart from meditation and allied spiritual disciplines that Gandhi casually referred to as “necessary preparations” for having the kind of experience he did in Yeravda Prison. Frankly, I haven’t found them “incredibly simple to understand” or “easy enough to practice”! Stilling the mind is no joke in our sense-bombarded, superficial, dizzyingly rapid, and consequently violent civilization.

We need a new civilization, a new culture. Where are we going to get it? The wisdom tradition is the reservoir to which we have to return today for our cultural renewal. I’ve been citing the Vedanta because it is a particularly pure and articulate source of that tradition. On Indian soil it gave rise to Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and the practice of meditation. That last is primarily, for me, why it can give rise to a cultural and spiritual renewal on our soils today.

Most common Indians in their 700,000 villages recognized—for their culture had prepared them to—that Gandhi was much more than a political revolutionary. As one of them said during the freedom struggle, “God sends a Mahatma Gandhi every thousand years.” When we think of Gandhi we think mostly, as we should, about ahimsa (Skt: non-violence), the great discovery that you can resolve conflicts without trying to use the same destructive energy that caused them. With this discovery, or rediscovery, he was able to rescue India—and in her wake countless other countries, including imperialist ones—from the scourge of colonial domination. But it’s worth realizing also that he rescued an ancient civilization from cultural domination, because that civilization contains other important gifts that we need and are free to claim.

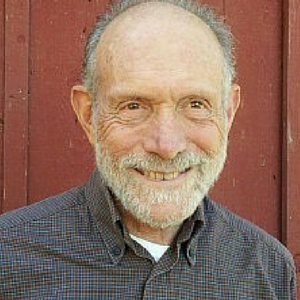

Michael Nagler is professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, a student of Sri Eknath Easwaran, founder of the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, and author of The Search for a Nonviolent Future, Our Spiritual Crisis, and Hope or Terror: Gandhi and the Other 9/11.

Source Citation

Nagler, Michael. 2008. Spirit and science in the Vedanta. Tikkun 23(1):61-63.

[…] the post, ‘Spirit and Science in the Vedanta’ (http://archives.mettacenter.org/science-2/spirit-and-science-in-the-vedanta), Michel Nigler, founder and president of Metta Center, points out that Gandhi was able to marry […]