This guest post was contributed by George Cassidy Payne, the founder of Gandhi Earth Keepers International. He is also a writer, a domestic violence counselor, and an adjunct professor of philosophy. George lives and works in Rochester, NY. You can follow him on LinkedIn.

The most powerful force in the universe is not electromagnetism, gravity or time. The greatest force in the universe is Satyagraha, which technically means a firm or steadfast adherence to Truth. Satyagraha is the most powerful force in the universe because it is the universe. It is the moral dimension of the universe revealing itself through social and political action.

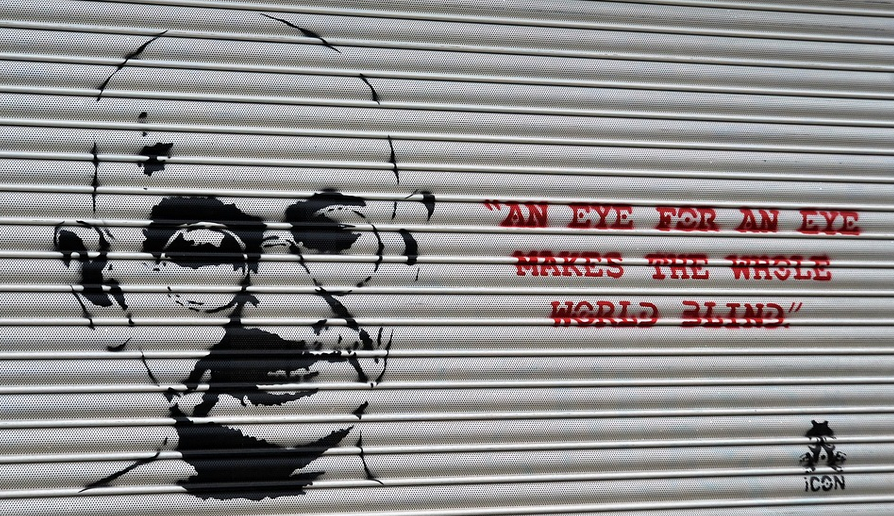

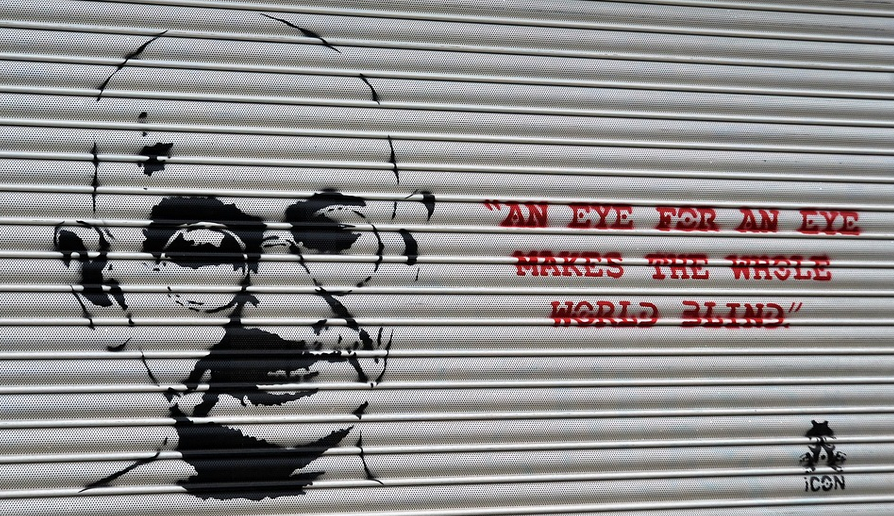

Mohandas Gandhi coined the term in 1906 while leading a nonviolent resistance movement against the British. He wrote:

None of us knew what name to give to our movement. I then used the term “passive resistance” in describing it. I did not quite understand the implication of “passive resistance” as I called it. I only knew that some new principle had come into being. As the struggle advanced, the phrase “passive resistance” gave rise to confusion and it appeared shameful to permit this great struggle to be known only by an English name… I thus began to call the Indian movement “satyagraha,” that is to say, the Force which is born of Truth and Love or non-violence, and gave up the use of the phrase “passive resistance” in connection with it, so much so that even in English writing we often avoided it and used instead the word “satyagraha” itself or some other equivalent English phrase. This then was the genesis of the movement which came to be known as Satyagraha, and of the word used designation for it.

Tactically, there are four main components that must be in place to activate Satyagraha. Firstly, a Satyagrahi must comprehend that all life is interconnected. From the ant to the aurora borealis, all life forms-including physical, mental and spiritual-are one at the source of their creative purpose.

The second principle is that persuasion overcomes coercion. That is to say, there is a long term advantage to convincing an adversary to understand and empathize with your perspective. Compelling opponents through intimidation or bribery is only temporarily effective, and it always has unintended consequences.

Thirdly, a Satyagrahi knows that ends and means must be aligned. Mohandas Gandhi referred to a surgeon who uses contaminated tools and expects a successful operation, which is an attitude that is both illogical and irresponsible.

Fourthly, a Satyagrahi is transparent in all matters. In any struggle the truth is pursued in good faith, with an open mind, and with sincerity. Gandhi once wrote, “Power is of two kinds. One is obtained by the fear of punishment and the other by acts of love. Power based on love is a thousand times more effective and permanent then the one derived from fear of punishment.”

Underlining each of these four components is a conscious belief in the spectacle of bravery—the type that can only be manifested through voluntary acts of suffering. If you would conquer another do it not by outside mechanisms but by creating inside their own personality an impulse too strong for his/her previous tendency. In this way Satyagraha taps into the “Law of Reversed Effect,” which states: “The greater the conscious effort, the less the subconscious response” or understood another way: “Whenever the will (conscious mind) and imagination (subconscious) are in conflict, the imagination (subconscious) always wins.”

A Satyagrahi knows that our ancestors from the dawn of life have suffered pain and deprivation-it is part of our collective nervous system. When others see bravery in action, there is an imagination-stimulus that gets galvanized. Of course this impulse may be crusted over by custom, prejudice and hostile emotions, but it is still ingrained in all of us. Inevitably, a nonviolent resister submitting themselves to bodily suffering for the sake of a noble cause rouses people’s moral conscience. Since feelings are more contagious than appetites, no other strategy is more effective in combating injustice.

When these four components are in place, there is almost nothing that the force of Satyagraha cannot achieve. It literally has the power to bring down dictators without firing a single shot. Satyagraha can make the proud see the plight of babes and it can make children mightier than the most formidable systems of oppression. Satyagraha brings refreshing aid to the sick and it uses the healing qualities of nature to bring health to the masses. Older than the hills, Satyagraha is an infinite, everlasting goodness that makes constellations burn with passion and the eyes of the poor glow with dignity.