Turning Our Backs on Consumerism

By Eknath Easwaran

As human beings, our greatness lies not so much in being able to remake the world—that is the myth of the “atomic age”—as in being able to remake ourselves.

—Mahatma Gandhi

In one of my favorite Sanskrit stories from ancient India, an ambitious rat goes to the Lord and asks to become a human being. The Lord grants his wish, and the rat is born into the world of people. He spends several lifetimes as a human being; finally, after quite a bit of experimentation and a great deal of grief, he goes back to the Lord and implores, “Please make me a rat again. Being a human is too hard—I’m just not cut out for it.”

I often think of this story when people tell me I am being idealistic about human nature. “It would be nice,” they say, “if we human beings could override impulses like fear, greed, and violence when we see that they threaten the welfare of the whole. But that’s just not realistic. Whenever there is a conflict between reason and biology, biology is bound to win.”

Arguing like this, some observers feel that we have passed the point of no return. Like lemmings, they seem to say, we must race to a destruction we ourselves shall have caused. I differ categorically—and for proof I have the living example of Mahatma Gandhi, who not only transformed fear, greed, and violence in himself but inspired hundreds of thousands of ordinary men, women, and even children in India to do the same.

When I was a student in my twenties India had been under British domination for two hundred years. It’s difficult to imagine what that means if you haven’t lived through it. It’s not just economic exploitation; generations grow up with a foreign culture superimposed on their own. When I went to college, I never questioned the axiom that everything worthwhile, everything that could fulfill my dreams, came from the West. The science, the wealth, the military power, all demonstrated unequivocally the superiority of Western civilization. It never occurred to most of us to look anywhere else for answers.

But then along came Gandhi, who was shaking India from the Himalayas in the north to Cape Kanniyakumari in the south. Everyone in the country was talking about Gandhi the statesman, Gandhi the politician, Gandhi the economist, Gandhi the educator. But I wanted to know about Gandhi the man. I wanted to know the secret of his power.

In his youth, I knew, Gandhi had been a timid, ineffectual lawyer whose only extraordinary characteristic was his big ears. By the time he came back to India from South Africa in 1915, he had transformed himself into such a mighty force for love and non-violence that he would become a lighthouse to the whole world. And I had just one driving question: What was the secret of his transformation?

My university was in Nagpur, a strategic location at the geographic center of India where all the major railways connecting north and south, east and west, came together like spokes in a wheel. Nearby lay the town of Wardha, a dot on the map thrown into international recognition as the last railway junction before Gandhi’s ashram. The rest of the way one had to travel on one’s own. I walked the few miles down the hot, dusty road to the little settlement that Gandhi called Sevagram, “the village of service.”

At Sevagram I found myself among young people from around the world—Americans, Japanese, Africans, Europeans, even Britons—who had come to see Gandhi and to help in his work. Whether a person’s skin was white, brown, or black, whether he or she supported or opposed him, seemed to make no difference to Gandhi: he related to all with ease and respect. Almost immediately, he made us feel we were part of his own family.

Indeed, I think that, in a private corner of our hearts, we all saw ourselves in him. I did. It was as if a precious element common to all of us had been extracted and purified to shine forth brightly as the Mahatma, the Great Soul. That very commonness was what moved us most—the feeling that in spite of all our fears and resentments and petty faults we too were made of such stuff. The Great Soul was our soul.

At that time, of course, there were many observers who said Gandhi was extraordinary, an exception to the limitations that hold back the rest of the human race. Others dismissed him—some with great respect, others with less—as just another great man who was leaving his mark on history. Yet, according to him, there was no one more ordinary. “I claim to be an average man of less than average ability,” he often repeated. “I have not the shadow of a doubt that any man or woman can achieve what I have, if he or she would make the same effort and cultivate the same hope and faith.”

The fact is, while most people think of ordinariness as a fault or limitation, Gandhi had discovered in it the very meaning of life—and of history. For him, it was not the famous or the rich or the powerful who would change the course of history. If the future is to differ from the past, he taught, if we are to leave a peaceful and healthy earth for our children, it will be the ordinary man and woman who do it: not by becoming extraordinary, but by discovering that our greatest strength lies not in how much we differ from each other but in how much—how very much—we are the same.

This faith in the power of the individual formed the foundation for Gandhi’s extremely compassionate view of the industrial era’s large-scale problems, as well as of the smaller but no less urgent troubles we found in our own lives. Our problems, he would say, are not inevitable; they are not, as some historians and biologists have suggested, a necessary side effect of civilization.

On the contrary, war, economic injustice, and pollution arise because we have not yet learned to make use of our most civilizing capacities: the creativity and wisdom we all have as our birthright. When even one person comes into full possession of these capacities, our problems are shown in their true light: they are simply the results of avoidable—though deadly—errors of judgment.

Gandhi formulated a series of diagnoses of the modern world’s seemingly perpetual state of crisis, which he called “the seven social sins.” I prefer to think of them as seven social ailments, since the problems they address are not crimes calling for punishment but crippling diseases that are punishment enough in themselves. The first—and the one we will focus on here—is knowledge without character. It traces all our difficulties to a simple lack of connection between what we know is good for us and our ability to act on that knowledge.

Knowledge Without Character

To me, the central paradox of our time is that despite our powerful intellectual skills and our ingenious engineering and medical achievements, we still lack the ability to live wisely. We send sophisticated satellites into space that beam us startling information about the destruction of the environment, yet we do little, if anything, to stop that destruction.

As Martin Luther King, Jr., put it, we live in a world of “guided missiles and misguided men,” where few technical problems are too complex to solve but we find it impossible to cope with the most basic of life’s challenges: how to live together in peace and health. In our lucid moments we see that we are doing great harm to ourselves and our planet, but somehow, for all our intellectual understanding, we cannot seem to change the way we think and live.

This is not to say we are bad people. The problem is simply that we have not yet completed our education. When Gandhi speaks of knowledge without character, he is not implying that we know too much for our own good. He is saying that because we do not understand what our real needs are, we are unable to use our tremendous technical expertise in a way that might make our lives more secure and fulfilling. Instead, we treat every problem as if it were a matter for technology, or chemistry, or economics, even when it has nothing to do with these things.

Every day, for example, dozens of new products appear, promising to satisfy our deepest desires. We are barraged with messages—subliminal and otherwise—on billboards and in magazines, on television and in the movies, telling us that everything we are looking for in life can be found in a car or a bowl of ice cream or a cigarette.

The hidden message is that what we own or eat or smoke has the power to endow us with self-respect. Actually, I would say it is the other way around. Your car may be useful and comfortable, it may have a wet bar and a cellular phone, but that is not why it is dignified. You, a human being, are the one who gives dignity to your car by driving it. If it were not for you, that car would be only a hunk of metal.

Over the past fifty years, the automobile, like so many of our appliances and machines, has sped down the now-familiar psychological highway from desirable luxury to basic necessity to tyrannical master. We no longer choose to drive a car—we have to: there are so many things to do, so little time to do them, and so far to travel in between. We rush about from place to place, caught in a perilous game of catch-up, and the price is high: nearly fifty thousand Americans lose their lives in traffic accidents every year. The irony is, we are often in such a hurry that we can’t get anywhere. I have read that commute time in Tokyo and London now is often less by bicycle than by car; and to judge by rush hour on our freeways, our situation is not much different.

Worse than the loss of time, of course, is the threat to our health. In each of those cars, according to recent research conducted in Los Angeles, commuters are exposed to two to four times the levels of cancer-causing toxic chemicals found outdoors. And as it idles there on the freeway, the average American car makes a significant contribution to the greenhouse effect, pumping its own weight in carbon into the atmosphere each year.

These things are not secrets. We have all heard them many times before, but we find it hard to do anything about them. Our cities and towns have grown in such a way that we feel helpless without a car. And as our cities expand ever farther into the surrounding countryside, the situation promises to get even worse.

The problem is that the roots of our dependence on the auto go deeper than the desire for a convenient mode of transportation. There is a much more powerful force at work here—a force that characterizes almost every activity in industrial society: profit. Under the relentless domination of the profit motive, we have remade our country in the image of the automobile. As the political historian Richard Barnet writes, describing America in the middle decades of this century,

Buying highways meant buying motels, quick food eateries,…and the culture of suburbia….The highway system was the nation’s only physical plan, and more than anything else it determined the appearance of cities and the stretches in between. In choosing the automobile as the engine of growth, the highway and automotive planners scrapped mass transit.

Oil shortages and higher gasoline prices have led us to regret turning a blind eye toward such practices, yet we go on driving more and more, drilling new oil wells, making and buying more and bigger cars. In just one hundred years, urged on by the profit motive and the media conditioning that driving is entertainment and our car is an extension of our personality, we have used up nearly half of the world’s known petroleum reserves, fouled our air, and put our oceans and beaches at continual risk from oil spills.

Now, I have nothing against automobiles. I have a car, and I appreciate its utility. All I would say is, it is important to remember who is serving whom. If we were the masters of our machines—and our lives—we would have good, well-made cars and good roads on which to drive, but wouldn’t we also use them sparingly, so our children and our children’s children would have enough oil left to heat their homes?

Nor am I suggesting that there is anything wrong in a businessperson making enough profit to support his or her family in comfort—everyone should have this opportunity. But we have exaggerated the importance of profit out of all proportion to its natural place in business. We have become addicted to it, and that is a very dangerous situation.

Most addictions begin innocently enough. “Just one more helping, one more bowl of ice cream, one more cigarette, one more drink for the road.” That is how it starts—just one more: “Let’s sell just one more new car, make one more dollar, pump one more gallon of gas.”

When we give in to that desire repeatedly, with a second helping, a second smoke, a second drink, or a second sniff, it becomes a habit—not just one more but one every day: “The stockholders want to see this quarter’s profits rising above last quarter’s. Get the general manager on the phone and tell him to increase production, bolster demand, and heat up consumption. And do it yesterday.”

With a habit we still have a choice whether to give in or not, but when a habit continues long enough, we lose our power to choose. Our feeling of security becomes so closely attached to the thing we crave that we must have it, whatever the cost. The habit has become a compulsion, and we have become its servant. We will do anything for a profit, even if it means sacrificing our children’s precious seas, air, and earth. This is what Gandhi means by knowledge without character—a lack of connection between what we know to be in everyone’s long-range best interest and our ability to act on that knowledge. It has become the cornerstone of much of our business and our lives.

Transforming Our Character

Anyone who has tried to overcome a powerful addiction like smoking or drinking or overeating knows there can be a broad, dangerous chasm between what we know is good for us and our ability to act on it. Once a habit has been conditioning the nervous system for many years, beating a path to the refrigerator or the cigarette machine or the lotto counter, it has also carved a track far below the conscious level of the mind, in the hidden world of the unconscious.

When an addiction has established itself like this in the unconscious, it can have a devastating effect on behavior. No matter how much we are told about the dangers, we often find ourselves falling helplessly back into old habits. Once, while waiting for a friend at the hospital, I saw a paralyzed man in a wheelchair struggle for some time with a package of cigarettes. Despite the fact that he could hardly move, a powerful compulsion was telling him to get out a cigarette, lift it to his lips, and light it. Laboriously and painfully, he complied. It took him nearly a quarter of an hour.

Now consider another patient—ourselves.

Few people realize that many of the food items now sold in a typical American supermarket—from potato chips to tomatoes to frozen pizzas—need an injection of petroleum at every step of their production and marketing. Herbicide, fertilizer, insecticide, tractor fuel, processing fuel, plastic packaging, transportation to the supermarket, refrigeration: all these require fossil fuels in some form—usually petroleum. Why use all this oil, when we have managed to do quite well for millennia with only sun, water, and soil? As I understand it, the answer begins with a seed: not just any seed, but a seed created after years of research and development.

Farmers and food processors have begun using seeds produced by sophisticated hybridization techniques and genetic engineering to grow fruit or vegetables to meet shipping and processing needs, like a potato that makes a perfect potato chip or french fry, or a tomato with the best shape, skin, and consistency for canning. The only financial drawback to such seeds is that they require a host of petroleum and chemical products to achieve the high yields they promise. Ingeniously, many firms have overcome that drawback by acquiring their own chemical, petroleum, and farm equipment companies. Some have gone so far as to acquire a genetic engineering firm that can design seeds to require just the products their companies manufacture. In this way, they can almost give away the seeds and still make a handsome profit.

From the consumer’s point of view, I am afraid there are other drawbacks. Most of the tomatoes grown today are bred for profit, not nutrition; these are not the juicy, delicious tomatoes, ripened on the vine, you might once have tasted in your mother’s kitchen garden. They are hard, almost square hybrids, ripened on a truck and often covered with dangerous chemical residues. They are genetically engineered for high yield, attractive color, disease resistance, and ease of canning or shipping. Only after these things has taste been considered, and nutrition hardly at all.

Then why do we buy them? Why not demand something better? I would suggest that the answer is to be found not in our economics but in our mental state. We have been conditioned to look to food for our inner fulfillment. Food can entertain us, we are told. It is exciting; it is romantic; it is adventurous; it is dignified. Vast sums of money are spent trying to get us to buy a certain brand of potato chip or to prefer one brand of frozen pizza over another. In the midst of this carnival atmosphere, it is easy to forget that the real purpose of food is to nourish our bodies.

Doctors remind us frequently of the consequences—junk food and heart disease, pesticides and cancer—but health is not just a matter between us and our physician. The health effects of industrial agriculture go far beyond what happens to us when we eat its products. They pose an even greater risk to the food supply our children will depend on in coming decades.

Consider the many different ways petrochemical products are used in producing a bag of agribusiness corn chips. First, because agribusiness farms are usually very large, a vast amount of petroleum is needed to run all the machines that plow and fertilize the field, that plant, spray, and harvest the corn, and then process, package, and ship it.

But that is only the machinery. Contemporary hybrid seeds are designed to produce greater yields than ordinary seeds, but they work best only when used with high-nutrient artificial fertilizers, manufactured in a chemical factory, using petroleum as an ingredient and as a processing fuel. Then, to control insects, large quantities of powerful insecticides are used—introducing hundreds of toxic chemicals never before found in nature.

Now, high-nutrient chemical fertilizers nourish not only the corn but all sorts of other plants and weeds that compete with it. At the same time, insecticides harm the birds and insects that feed on those weeds. The sensible response might be to use less chemical fertilizer and insecticide and to apply them only when needed, if at all. But this kind of care is impossible on a huge farm, where the chemicals are applied with large machinery or by airplane, hundreds of acres per day. The profit-oriented solution is to come up with yet another product that can be sold to every farmer who uses chemical fertilizers: herbicides. With tremendous ingenuity, agribusiness engineers have even begun to match specific herbicides to the crop’s genetic pattern so the herbicide will kill everything but the corn.

There is a hitch, though. In all this innovation, a great deal of attention is paid to the ratio of gross income to net profit, to the glamorous appearance of an ear of corn, or to the ease with which it can become a corn chip. Yet little thought is given to the topsoil, that fragile layer of minerals, organic matter, and insect life on which almost our entire food supply depends.

Although chemical fertilizers contain many of the nutrients a crop needs, they lack the humus and organic matter needed to nourish what is, after all, a living ecosystem. The topsoil’s earthworms and microorganisms depend on that organic matter. So does the topsoil’s capacity to hold water and prevent erosion. When chemical fertilizers are used continuously, the soil literally begins to starve. It loses its ability to retain water, and it needs ever-increasing amounts of irrigation. Then, as herbicides and insecticides are applied every season, year after year—eventually poisoning the microscopic life of the topsoil—the most important element in world agriculture is reduced to lifeless dust.

It does not make sense. Perhaps it might if the foods we ended up with were better—better tasting or better for our health—but they are not. It might make sense if all these chemicals and oil helped the individual farmer, or made the earth healthier, or saved precious resources. But they do not. Or it might make sense if they really did ensure the safety and abundance of our food supply. They do just the opposite.

Petroleum-dependent agriculture may begin with a seed and the desire for profit, but it ends with us, when we reach for an item on the supermarket shelf. Without our cooperation and support, none of this would take place. We have helped in every stage, almost unconsciously believing that our dignity, fulfillment, and happiness are to be found in food or possessions or profits. We have become servants to our own unintended greed, and it is not a benevolent master.

In Gandhi’s perspective, it is up to individuals like you and me to reverse this situation. Environmental abuse and exploitation are not “necessary evils”—no evil is necessary. In fact, Gandhi went so far as to say that evil in itself is not even real; it exists only as long as we support it. The moment we withdraw our support—the moment we make the connection between what we know and how we behave—it begins to collapse. As the eighteenth century British statesman Edmund Burke put it, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Nevertheless, in our current situation, good men and women have little time to lose. At a breakneck pace, knowledge without character is making drastic changes in our atmosphere, our agricultural resources, our forests, and our seas. The cost in life is immeasurable.

The Power of Salt

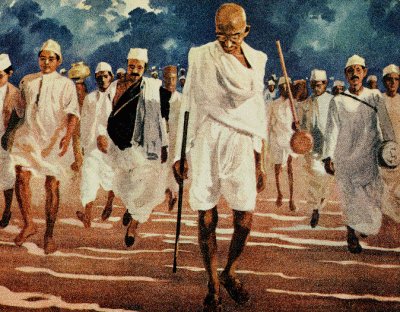

On March 12, 1930, when the British still had a firm grip on India, Mahatma Gandhi and seventy-eight of his disciples strode out of Sabarmati ashram toward the sea. In the twenty-four days that followed, they walked two hundred miles, picking up more and more companions as village after village turned out to cheer the Mahatma and raise the new Indian flag. By the time they reached their destination, the seashore at Dandi, the group numbered several thousand.

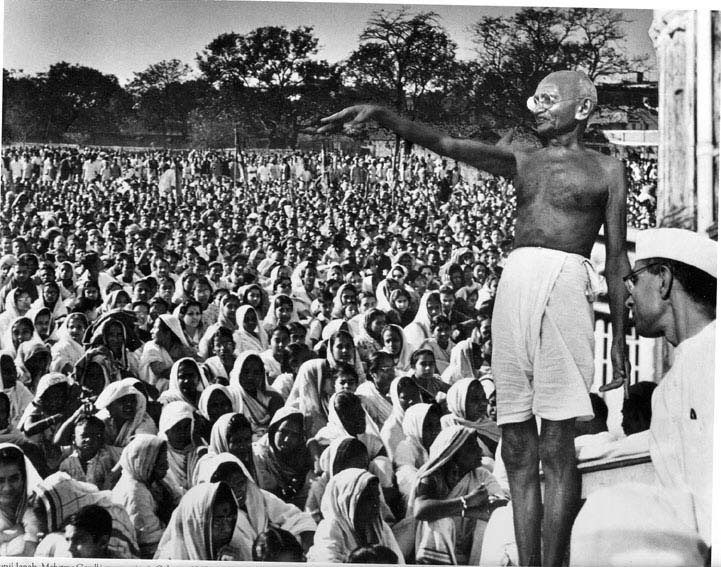

Earlier in March, Gandhi had sent a letter to the British viceroy protesting the Salt Act, which forbade Indians to make their own salt and left them dependent on a British monopoly for what is, in a tropical country, a necessity of life. The viceroy did not reply. To Gandhi, this was the “opportunity of a lifetime.” On the morning of April 6, before a huge crowd including reporters from around the world, Gandhi walked to the edge of the sea, picked up a pinch of salt, and set India free.

It was Gandhi’s genius to recognize that although the British had the power to establish a monopoly on salt, they could maintain that monopoly only with the cooperation of the Indian people. With his inspiration and guidance, millions of ordinary individuals changed their lives in a small but powerful way: they stopped buying salt from the British and began making it themselves. Almost immediately, Indians along the coast and across the country were making, buying, and using homemade salt. A hundred thousand were jailed, and many more suffered great hardships, but throughout the campaign, millions of Indians refused steadfastly and without violence to depend on the British for salt. This brilliant campaign, which restored India’s confidence in herself, was the turning point in her long struggle for independence. Afterward India knew she was free, and nothing the British did could halt her march toward freedom.

Today, in a modern industrial society like the United States, our most pressing need is not for salt or clothing or shelter. For most of us, all our basic needs have been met. But there remains a hunger for something more. We want to be somebody. We want to feel secure. We want to love. Without any better way to satisfy these inner needs, we end up depending on possessions and profit—not just for our physical well-being but as a substitute for the dignity, fulfillment, and security we want so much. Because we still believe happiness lies in remaking the world around us, we look for inner fulfillment outside ourselves, and this makes us easy prey for manipulation.

How, then, shall we free ourselves?

Let’s start in little ways, by trying to make the connection between what we know to be healthy for our planet and what we do in our daily lives. As many environmentalists have suggested, we could walk instead of taking the car, or carpool or use mass transit instead of driving alone—that would be a small salt march in itself, with the added benefit that the commute would not be so lonely or expensive or long. We could start buying organic vegetables; if possible, we might even grow them in our own backyards, using no pesticides or other harmful chemicals. That would be the modern equivalent of making salt. We would be healthier, and so would the topsoil.

Yet, even small changes like these seem difficult. We all have so little time to spare; and we ask ourselves, what good would it do anyway? This is understandable. Without Gandhi’s example, I think few Indians could have been persuaded that the British would be ushered out of India peacefully and gently and that a new independent nation of India would be founded—all by the power of salt.

The tasks facing us today are enormous, but it is the glory of human nature that there will always be those rare individuals who say, “Let there be dangers, let there be difficulties, let there be the possibility of death itself—whatever it costs, I want to live in the full height of my being, with my feet still on the ground but my head crowned with stars.” According to Mahatma Gandhi, this can be done only by facing difficulties that appear almost impossible. If that is so, our times offer an unparalleled opportunity.

Our hope for the future lies with these rare evolutionaries who are not content to wait for others to change before they throw themselves into this unimaginably difficult task. “Strength of numbers is the delight of the timid,” said Gandhi. “The valiant in spirit glory in fighting alone.” What is the satisfaction in drifting along with the current? True satisfaction lies in swimming against the current of conditioned self-interest. It is dangerous, of course, but that is why it makes you glow with vitality. It is strenuous, but that is what makes your will and determination and dedication grow strong, your senses clear, your mind secure, and your heart overflowing with love and the desire to give and serve.

Gandhi is a supreme example. He wanted so deeply to help the world that he dedicated his life to siphoning every trace of self-interest out of his heart and mind, leaving them pure, radiantly healthy, and free to love. It took him nearly twenty years to gain such control of his thinking process, but with every day of demanding effort he discovered a little more of the deep resources that are within us all: unassuming leadership, eloquence, and an endless capacity for selfless service.

In me, in you—in every human being—burns a spark of pure compassion: not physical or even mental, but deeply spiritual. Our bodies may belong to the animal world, but we do not. The animal, to a great extent, lives subject to the force of conditioning, going after its own food and comfort. But we have the capacity to turn our back on profit or pleasure for the sake of others—to rebel deeply and broadly against our conditioning and build a new personality, a new world. It is our choice whether to exercise that capacity, but we do have the choice.

Spiritual teacher Eknath Easwaran founded the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation in 1961. His books includePassage Meditation and translations of the Classics of Indian Spirituality.

From The Compassionate Universe by Eknath Easwaran, founder of the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation, copyright 1993; reprinted by permission of Nilgiri Press, P. O. Box 256, Tomales, CA 94971.

Ever since Paul Hawken published Blessed Unrest(2007), it has been clear to many that the progressive world is a million projects in search of a movement. A movement, Hawken reminded us, has “leaders and ideologies; … people join movements study [their] tracts, and identify themselves with a group,” while the Occupy movement today seems to be just a continuation of the style that is “dispersed, inchoate, and fiercely independent. It has no manifesto or doctrine, no overriding authority to check with.” Can #Occupy provide the framework that will pull these far-flung but inwardly resonant energies together—and in so doing become a force that could, in Gandhi’s terms, “o’ersweep the world”? I believe we can make that happen, and we should, because in any case, as Gandhi also said, a movement that is simply against something cannot sustain itself.

Ever since Paul Hawken published Blessed Unrest(2007), it has been clear to many that the progressive world is a million projects in search of a movement. A movement, Hawken reminded us, has “leaders and ideologies; … people join movements study [their] tracts, and identify themselves with a group,” while the Occupy movement today seems to be just a continuation of the style that is “dispersed, inchoate, and fiercely independent. It has no manifesto or doctrine, no overriding authority to check with.” Can #Occupy provide the framework that will pull these far-flung but inwardly resonant energies together—and in so doing become a force that could, in Gandhi’s terms, “o’ersweep the world”? I believe we can make that happen, and we should, because in any case, as Gandhi also said, a movement that is simply against something cannot sustain itself.