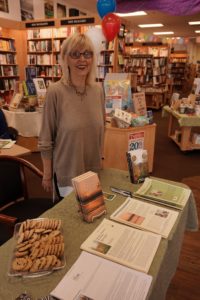

Author Patty Somlo at Copperfield’s Books in Santa Rosa, CA. Photo courtesy of Patty Somlo.

Where do art and literature fit in the broader picture of peace and justice? That’s a question I’ve been fascinated with since 2009, when I served as Co-Founding Editor for a small book publisher. Part of my work involved reviewing manuscripts, contracting authors, and directing the design process. That’s how I first met the author Patty Somlo—by signing on her short story collection, From Here to There and Other Stories.

Since then, I’ve had the pleasure of working with Patty elsewhere, including here. Through my former Metta Center role as Editor & Creative Director of Nonviolence magazine, I selected a couple of Patty’s stories for publication, because they reflected the organization’s mission to advance a higher image of the human, not to mention a greater sense of justice and dignity.

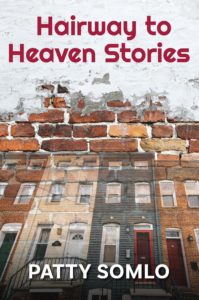

In Patty’s latest collection, Hairway to Heaven Stories, faith and spirituality play a key role. The 15 stories present a microcosm of many US neighborhoods in cities where people of different races, ethnicities, class and sexual orientation live in close proximity to one another, with neighbors being both strangers and friends.

Hairway to Heaven was recently published by Cherry Castle Publishing, a black-owned press committed “to practice literary equality and to embrace work that is informed by the social, political and cultural vigor of our times.”

So what do you think: Where do art and literature fit in the broader picture of peace and justice? Read on for Patty’s take.

What’s the inspiration behind this collection of short stories?

What’s the inspiration behind this collection of short stories?

Hairway to Heaven Stories is a linked short story collection set in what had been a predominantly African American neighborhood that is now in the process of gentrification. The initial inspiration for the book was my desire to write about gentrification and the pricing out of low and moderate-income residents from many American cities. One morning, I heard a story on National Public Radio about a traditionally African American neighborhood in Washington, D.C. that was undergoing gentrification. A community leader who was interviewed said that many longtime residents of the neighborhood could no longer afford to live there. I was saddened by this news. I knew the neighborhood, because I had spent time there many years ago, observing classes at Malcolm X Elementary School, while finishing my bachelor’s degree in Art Education.

I had also experienced the effects of rising rents on a more personal level. In San Francisco, where I had lived for 20 years, and where my husband was born and started elementary school, rents and real estate prices started soaring in the 1990s with the dot-com boom, and then just kept on climbing. People were being evicted all the time, including low-income elderly, from homes they had lived in for decades. Once evicted, there were no places in the city these people could afford. Like many moderate-income renters in San Francisco, I worried that my husband Richard and I would be next. Finally, in 2000, when we wanted to move out of our noisy flat, we couldn’t afford anything in the Bay Area. So, we were forced to leave California.

I grew up in a military family that moved every year or two and continued to move around a lot as an adult. Home for me has been an elusive concept, so home and place have prominent roles in my work. I was attracted to the idea of a linked collection that centered on people living in the same neighborhood, with the neighborhood almost serving as another character. In several different cities, I lived in African American neighborhoods that had started to gentrify. These neighborhoods were usually more diverse than the rest of the city, which made them interesting places to live. When I considered writing this book, a time of so much division in this country, and misunderstandings about what it means to be an American, I realized that these neighborhoods represent what I view as the real America. A desire to portray the America I know was also part of my interest in writing this book.

The neighborhood in “Hairway to Heaven” is a fictionalized area set around Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard in Portland, Oregon. There is such a neighborhood, North Portland, and I did use elements of the real neighborhood in my book. But I also used aspects of neighborhoods I had lived in, including my Southeast Portland neighborhood, as well as making things up.

When my husband and I could no longer afford to live in San Francisco, we moved to a Portland neighborhood in the process of change. At one time, the neighborhood had been quite rough, with lots of crack houses. When we moved there, people were buying the rundown Victorians and bungalows and fixing them up. But there were still problems that carried over from the old neighborhood, ones that are common in urban America, including way too many homeless people living on the streets, petty crime and drug dealing.

One morning, I was on the 15 Belmont bus headed to work  downtown. The bus always stopped a few blocks from my house to pick up and let off folks at the methadone clinic. I had become quite familiar with the men and women who went to the clinic, since I rode with them every day on the bus. They all knew one another and talked loudly, a great source of material for a writer. Suddenly, a story idea popped into my mind, about a substance abuser named Leticia, thinking that she saw Jesus on her last day of rehab. I quickly jotted it down in the little notebook I always carry and that grew into the title story, “Hairway to Heaven.”

downtown. The bus always stopped a few blocks from my house to pick up and let off folks at the methadone clinic. I had become quite familiar with the men and women who went to the clinic, since I rode with them every day on the bus. They all knew one another and talked loudly, a great source of material for a writer. Suddenly, a story idea popped into my mind, about a substance abuser named Leticia, thinking that she saw Jesus on her last day of rehab. I quickly jotted it down in the little notebook I always carry and that grew into the title story, “Hairway to Heaven.”

“Outta Here,” a story in your book, ran in the Democracy Issue of Nonviolence (Summer/Fall 2016). That story features a character named DaVon Richards, a 14 year-old black boy with special needs. He’s fatally shot by a police officer, and we never learn of an investigation or anyone being held accountable. Were such omissions an intentional creative decision?

Yes. First of all, I felt we all knew how that would end, since the follow-up to shootings of unarmed black men nearly always have the same ending, with the officer not being charged. But the second reason is because I had a healing motivation for writing the story, which is why I wrote a somewhat more hopeful ending. When I started writing the story, I was, and still am, angry and sad about these killings of innocent black and brown men and youth and of feeling powerless to change it. Writing this was a way to grieve. It was also a way to reimagine a real-life tragedy and bring in some hope. While “Outta Here” is about a young African American boy shot holding a baseball bat the officer assumes is a weapon, I was moved to write this story following the 2013 killing of a thirteen-year-old Latino boy named Andy Lopez, by a Sonoma County deputy sheriff in the City of Santa Rosa, California, where I live now. Andy was holding a toy gun and the deputy said he thought it was a real gun.

In “Outta Here,” following the killing of DaVon Richards, money is raised for a baseball diamond in the neighborhood where the boy was killed. In my real-life inspiration, people in Andy Lopez’s neighborhood of Southwest Santa Rosa initially created a memorial park for him, near the site of his death. But they also fought for a real park, and their efforts succeeded. Two years ago, the county board of supervisors approved several million dollars more for the park, along with a name: Andy’s Unity Park. I recently read that construction has just been completed. It will be the first-ever park in Andy Lopez’s neighborhood.

A park, of course, doesn’t make up for a life. But it is a small step in addressing the needs of young people in neighborhoods that are so often neglected. It makes a statement about valuing people, and that was part of what I wanted to convey in my story.

Your stories tend to lean towards awareness and justice. Is there a relationship for you between entertainment and raising our levels of human consciousness?

Yes and no. I don’t intentionally write fiction to raise consciousness. I’m mostly drawn to writing stories that reveal something about the human condition. I didn’t grow up in a close family, I don’t have children of my own, and as a military kid, I often felt like an outsider. I observed and listened to other people a lot, as a way to try and fit in when we moved to a new place. I’ve continued to do that as an adult, so observing people out in the world inspires my stories. These stories often involve the big issues of our time because they concern me – inequality, violence, racism, xenophobia, misogyny, and immigration. My work often has a magical realist element to it, a type of fiction I fell in love with from reading Latin American and South Asian writers – and, of course, Charles Dickens! Magical realism can shine a spotlight on injustice. I’ve heard magical realism described as getting to the roots of reality, letting the reader see what can so often be hidden. Sometimes, this is done by making fun of reality.

For instance, in one of the stories in this collection, “Emergency Room,” a woman with a badly injured hand goes to the neighborhood emergency room for help. It turns out that the people she begins to meet there have been waiting for hours, some even an entire day, and no one has come out to help them. The story takes a real situation in the United States, that of often unaffordable and, therefore, inaccessible medical care, and exaggerates it a bit, to shine a light on the unfairness and absurdity of the system.

So, yes, I do think my stories can raise consciousness, and I, of course, hope they do.

In these times of “post-truth,” do you see a unique role for fiction to play in disseminating the truth?

Yes, definitely. Even many years ago when I worked as a journalist, I felt that the whole true story often wasn’t told by the media. In order to cut through the misinformation, I tried to interest readers in sometimes divisive issues by focusing on human stories. Fiction, even more than nonfiction, can help readers know and empathize with people they might otherwise not care about. Fiction works when whole, multidimensional characters are created, rather than stereotypes, and can help dispel stereotypes.

What about the link between art and peace—is there one for you as a writer?

Yes. Artists, writers and musicians have always been integral to movements for peace and justice, whether in the Civil Right movement, the anti-apartheid movement, or various anti-war movements. At this moment when we are seeing a renewed and energized effort to stop gun violence, I just saw a call for writing about individual responses to gun violence. Artists, writers and musicians nearly always are at the forefront of bending the arc a bit more toward peace and justice.

A former journalist, Patty Somlo has published three short story collections: From Here to There and Other Stories (Paraguas Books), The First to Disappear (Spuyten Duyvil) and Hairway to Heaven Stories. She has been a finalist in the International Book Awards, Best Book Awards, and National Indie Excellence Awards. She has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and one of her essays was selected as Notable for Best American Essays 2014.

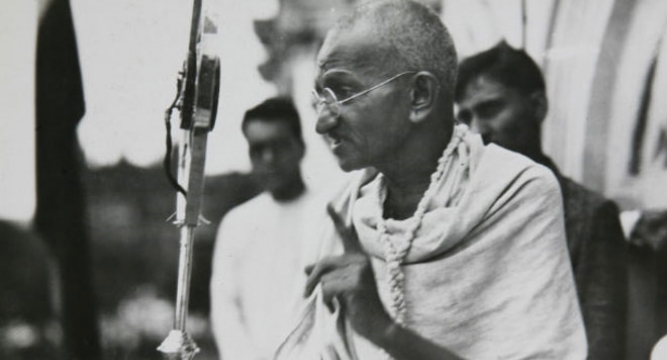

Bengali Woman at the Spinning Wheel – a photogravure by Martin Hurlimann

Bengali Woman at the Spinning Wheel – a photogravure by Martin Hurlimann

On my rare visits to LA, I am always impressed (negatively) by the blatant violence of the billboards advertising films and TV. This past weekend was no exception. Apparently, there are fashions in violence. A while back it was crime, then a particularly sick one: the dead – zombies slouching toward you every other street. Now it’s hulks. I pay as little attention as possible, so it took me a while to realize there was something odd about one I had just passed. While it looked like hulks from a Jurassic swamp or foreign planet, it was actual people: Navy Seals, to be precise. A recruitment poster. But the men – it even said something like “incredible men” as part of the advert – were so encrusted with weapons and armor, huddled in their trenches, they looked thoroughly un-human. What an allegory.

On my rare visits to LA, I am always impressed (negatively) by the blatant violence of the billboards advertising films and TV. This past weekend was no exception. Apparently, there are fashions in violence. A while back it was crime, then a particularly sick one: the dead – zombies slouching toward you every other street. Now it’s hulks. I pay as little attention as possible, so it took me a while to realize there was something odd about one I had just passed. While it looked like hulks from a Jurassic swamp or foreign planet, it was actual people: Navy Seals, to be precise. A recruitment poster. But the men – it even said something like “incredible men” as part of the advert – were so encrusted with weapons and armor, huddled in their trenches, they looked thoroughly un-human. What an allegory.

What’s the inspiration behind this collection of short stories?

What’s the inspiration behind this collection of short stories? downtown. The bus always stopped a few blocks from my house to pick up and let off folks at the methadone clinic. I had become quite familiar with the men and women who went to the clinic, since I rode with them every day on the bus. They all knew one another and talked loudly, a great source of material for a writer. Suddenly, a story idea popped into my mind, about a substance abuser named Leticia, thinking that she saw Jesus on her last day of rehab. I quickly jotted it down in the little notebook I always carry and that grew into the title story, “Hairway to Heaven.”

downtown. The bus always stopped a few blocks from my house to pick up and let off folks at the methadone clinic. I had become quite familiar with the men and women who went to the clinic, since I rode with them every day on the bus. They all knew one another and talked loudly, a great source of material for a writer. Suddenly, a story idea popped into my mind, about a substance abuser named Leticia, thinking that she saw Jesus on her last day of rehab. I quickly jotted it down in the little notebook I always carry and that grew into the title story, “Hairway to Heaven.”