by Annie Hewitt

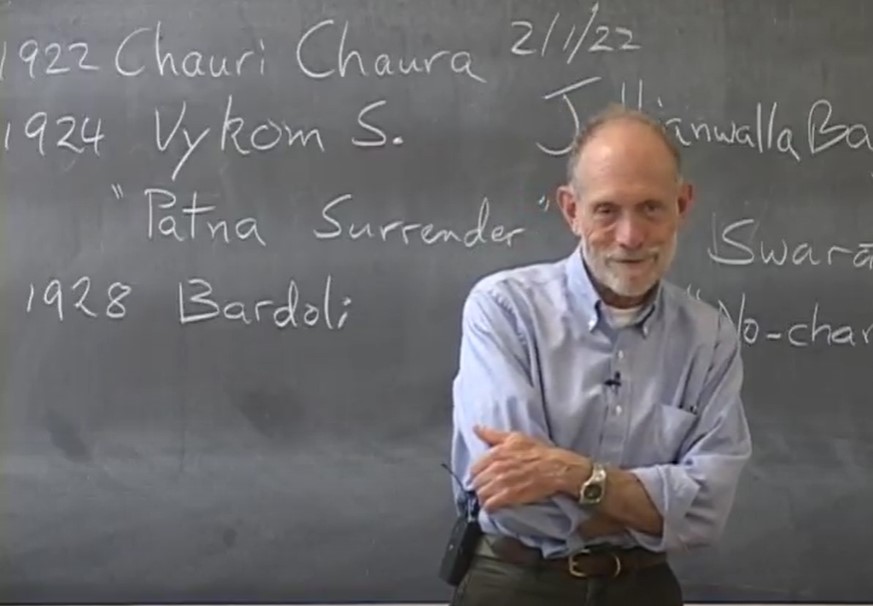

The Patna Surrender (1922-1924) was Gandhi’s response to a split in the Congress Party based on whether or not to take part in local councils set up by the British. On one side was Nehru and his supporters, convinced that Indians should participate in the councils even though they were largely symbolic and wielded very little concrete power. On the other side was Gandhi, who believed that for Indians to join ineffective councils was to take part in a political lie, ultimately at their own expense.

Gandhi finally gave up and yielded to Nehru — what made him cave in and surrender his position?

If we stop and look at this question, we can see that the language used is not neutral, certain terms connote weakness:

‘Give up’

‘Yield’

‘Cave in’

‘Surrender’

What happens when we look at these words afresh, can we break free of our habitual understanding and in this, can we reconceive Gandhi’s decision? Gandhi himself saw the Patna surrender as a victory, an expression of strength. How could this be?

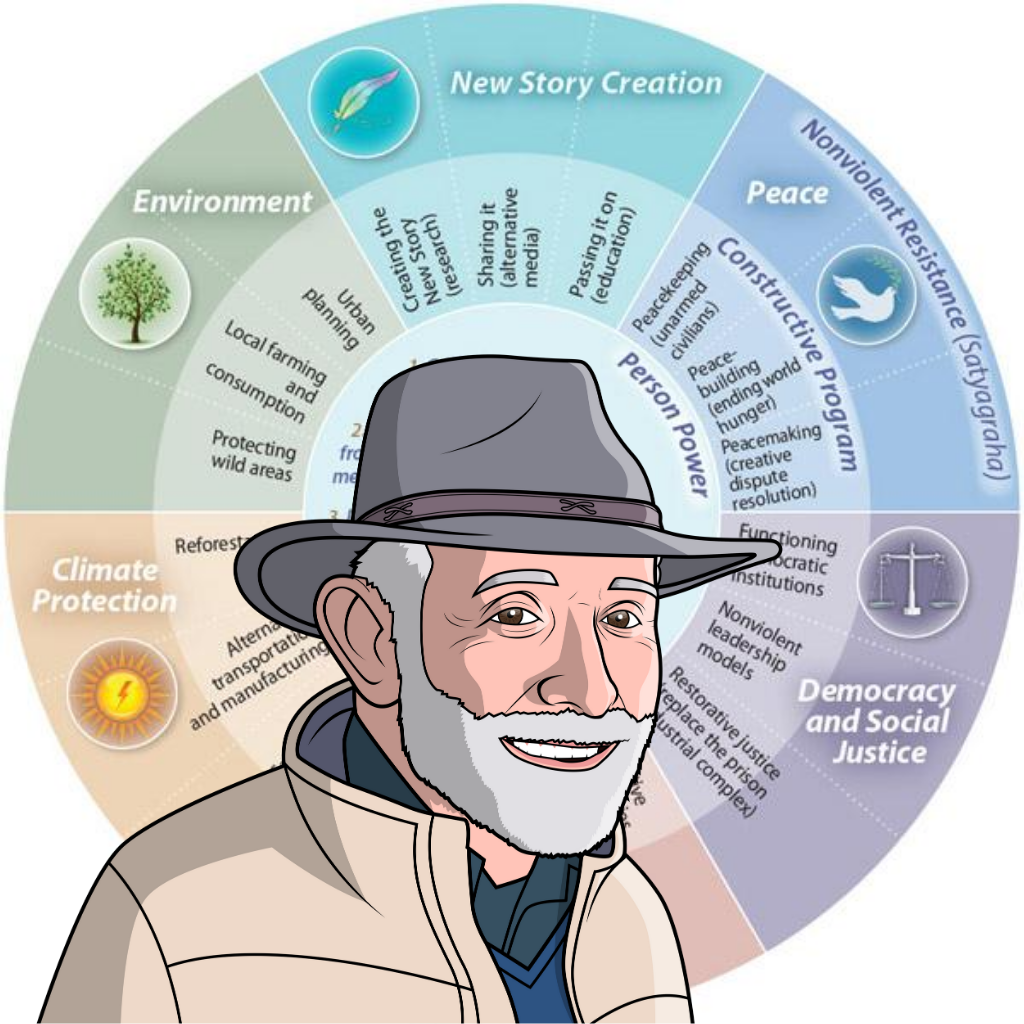

Professor Nagler explains that ‘caving in’ for Gandhi is in fact a source of power; caving in creates space. In a conflict, when one party gives up something, whether a physical position or a demand, that act of letting go makes more room for both sides. This room in turn allows for movement, the possibility that opposing parties might come together and move forward united towards a larger, common goal. In this, Gandhi’s decision to give up/yield/cave in/surrender might be seen as an instance of Boulding’s ‘integrative power’ in action.

Yielding thus need not be understood as a sign of frailty nor does it entail abandoning principles — quite the contrary! Gandhi’s view suggests that surrendering is an act of creation which gives something to both sides. It reflects the wisdom found in a wider perspective, an awareness of our shared humanity, which is always there, underlying all our relationships, even if temporary masked by the narrow parameters of an immediate conflict.

Haemon, in Sophocles’ Antigone expresses a similar point when talking to his father who rigidly clings to his position in opposition to his niece. Haemon encourages King Creon to be flexible, to adapt and bend, making space for Antigone’s position. In the end, far from expressing weakness, nature itself reveals this kind of expansive action to be a way to survive and grow.

Please don’t be quite so single-minded, self-involved, or assume the world is wrong and you are right. …it’s no disgrace for a man, even a wise man, to learn many things and not to be too rigid. You’ve seen trees by a raging winter torrent, how many bend and sway with the flood and salvage every twig, but not the stubborn—they’re ripped out, roots and all. Bend or break.