By Metta blogger PHILIP WIGHT

“You cannot help loving those that love you and you cannot hurt those that trust you.” –Badshah Khan

Muslim nonviolence. For most, this phrase conjures images of the Arab Spring and stories of civil resistance in Tunisia and Egypt. But there is one man in history that most embodies this phrase: Badshah Khan.

Born Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the Northwest frontier province of what was British India (now Pakistan), Khan devoted his life to freedom against oppression, nonviolent resistance, social justice, and a Constructive Program of self-sufficiency. Khan earned the title “Badshah”—or “king of khans”—early in his life by organizing his fellow Pashtuns (or Pathans), opening schools, and effectively resisting the British through nonviolence.

Called by one historian the “Muslim St. Francis,” Khan affirmed, “It is my inmost conviction, that Islam is amal, yakeen, muhabat” (selfless service, faith, love). Imprisoned for over a third of his life, Khan became a vegetarian and a devoted disciple of Gandhi. Rejecting the violence of his Pashtun culture and the violence of other Muslim peoples, Khan believed “not one in a hundred thousand knows the true spirit of Islam.”

Khan saw the violence around him for what it was–destructive and cyclical. He argued the Pashtun peoples’ self-destructive tendencies prevented them from gaining independence from Great Britain. Yet Khan understood the Pashtun’s indomitable nature could also be harnessed for a peaceful future. Only such a fearless people—Khan believed—could form an army of nonviolent soldiers.

Badshah Khan called his organization the Khudai Khidmatgars—or Servants of God—but they were commonly called “Red Shirts” after their uniforms (a fact that enabled the British to stigmatize them as “communists”). Khan’s men took an oath of nonviolence, promised to live a simple life, and to devote at least two hours a day to social work. The Red Shirts’ mission was to not only rid society of the violence brought by imperialism, but also the cultural violence of the Pathan people. Khan clarified, “This is basically a social movement, not a political movement.”

The Red Shirts opened new schools, fed the poor, helped communities build infrastructure, and maintained order at large Pashtun gatherings. Due to their fierce nature and effective organizing—and aroused by a massacre of peaceful resistors in Peshawar in 1930—Khan’s “army” soon mustered nearly 100,000 nonviolent soldiers. They swore to “lay down their own lives and never take any life.” The Red Shirts kept their oaths; they refrained from violence when the British fired into crowds of unarmed men and women, killed hundreds, and imprisoned tens of thousands of civil resisters.

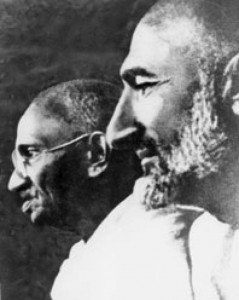

Gandhi inspired Khan with his campaigns of nonviolent resistance in South Africa, but the two men didn’t meet until 1926. Speaking of Gandhi’s ideas on nonviolence, Khan said, “They changed my life forever.” The two became close friends and allies in the cause of independence through nonviolence. Gandhi respected Khan’s faith, especially his devotion devoid of fanaticism and his broad-minded faith that respected other cultures and religions. Khan would read the Koran to Gandhi, often borrowing the Mahatma’s glasses when he had forgotten his own. When a Hindu extremist lambasted Gandhi for allowing the Koran to be read by Khan at a prayer meeting, Gandhi responded: “You are doing no good to Hinduism by your unreasoning fanaticism.”

Though the two men began constructive work independently, Khan’s eventual vision of a peaceful community was based on Gandhi’s Constructive Program, which emphasized cottage industries and the ideal of self-sufficiency. As Gandhi counseled, “wear only the clothes that we ourselves produce, eat only fruits and vegetables that we raise there, and set up a small dairy to provide us with milk.” Both men understood that a self-sustaining local economy could eliminate the poverty and material dependence responsible for not only their continued oppression but, in a larger sense, violence and war.

In building a culture of peace, Khan also fought against the Islamic system of purdah, which restricted Muslim women. He argued, “God makes no distinction between men and women…It is a grave mistake we have made in degrading women.” Khan empowered his principles by establishing girls’ schools—an exceptionally rare occurance on the Muslim frontier. “When freedom has been won,” Khan told a group of women, “you will have an equal share and place with your brothers in this country.”

Khan and his Red Shirts were a crucial force in winning India’s independence, yet this victory only brought more challenges. Gandhi and Khan had both rejected partitioning India, believing a divided state would bring neither peace nor justice. The newly formed state of Pakistan quickly disbanded the Red Shirts, but Khan spent the rest of his life—often in prison—fighting against military rule and religious extremism. Khan was the 1962 Amnesty International Prisoner of the Year and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. When he died, in 1988 at the age of 98, fighting stopped to honor the cortege that conveyed his body back to Afghanistan. His example endures to show that all people, from all religions, can rise above cultural narrowness and political repression to engage the power of nonviolence.

This was a perfect article to read on the anniversary of the tragic events of September 11th. May we all embrace the peace and compassion of our many different faiths and work hand-in-hand to rise above the hatred and violence that plagues our human family. These two great leaders should inspire us all.

[…] Where there are leaders these are supported by the persistence of other activists, such as in Bashah Khan’s 100,000 nonviolent soldiers and countless other people we usually have not even heard of. Peace is made between non famous […]

[…] Wo es Führer gibt, werden diese durch die Beharrlichkeit anderer Aktivisten unterstützt, wie z Bashah Khans 100.000 gewaltfreie Soldaten und unzählige andere Leute, von denen wir normalerweise noch nicht einmal gehört haben. Täglich […]