I was deeply saddened to read last week of the death by suicide of Cmdr. Job Price who was with a Navy SEAL team in Afghanistan.

I was even sadder when I realized that the hopeful idea that sprung up in my mind was naive: “Now maybe people will understand why soldiers commit suicide.” The only reasons for his suicide that the media could offer were the usual suspects: it was a bad deployment, “a cautionary tale of how men were ground down by years of fighting and losing comrades,” and of course, the old fallback that puts a stop to the whole inquiry, “no one knows why.”

The fact is, we know very well why soldiers and veterans commit suicide – if we allow ourselves to know it. In his book, “On Killing,” Lt. Col. David Grossman describes that from the beginning of the historical record up to the Korean War, soldiers were extremely reluctant to kill their fellow human beings, going so far as reloading weapons they hadn’t fired. Muskets were found on the battlefields of the American Civil War with as many as eighteen balls rammed down the barrel in this pretense. And what Grossman concluded has been strongly confirmed by science: human beings have a strong, inherent inhibition against killing and injuring their fellows.

We can, of course, be trained or conditioned to go against this inhibition; but what results is what psychologist Rachel MacNair calls Perpetration-Induced Traumatic Stress (PITS), a form of PTSD that affects not only combat soldiers but police officers, prison guards who carry out “legal” executions, and many others. In any of these people, the cognitive dissonance can lead to suicide. This inhibition is arguably what makes us human; we cannot violate it without serious consequences, no matter what society or our conscious minds tell us about it’s being necessary, or even glorious.

This inhibition, which we should be very proud of, goes back so far in evolution that we are born with “mirror neurons” in our brain that cause us to feel what others feel. Distinguished neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni of UCLA says, “Although we commonly think of pain as a fundamentally private experience, our brain actually treats it as an experience shared with others.”

In Grossman’s second book, “Let’s Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill,” he reports that after the military had discovered how few men were actually firing their weapons in combat situations, it set about conditioning recruits to override the inhibition. In some cases, they simply used the same games that our children are playing on their X-Box or Playstation (hence Grossman’s title). They were very “successful” – that is, in increasing the firing rate – not in changing human nature.

A SEAL is supposed to be beyond all this, but the case of Cmdr. Price shows it isn’t so. Now, I have no idea what goes into the making of a Navy SEAL, but as part of basic training in the regular army, recruits shout out in unison when asked the purpose of the bayonet “to kill, kill without mercy.” But to be without mercy is to be without your humanity. And this is what veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan are telling us: “I lost my soul in Iraq,” “I no longer like who I am,” etc.

When will we realize that the reluctance to kill and injure is not an inconvenience, but a precious capacity that we should celebrate and reward and that we could use as a guide to how we can and should live?

There was, to be sure, one hint in the press: just before he killed himself, Cmdr. Price had in his pocket a report about an Afghan girl who had died in an explosion near the base. But it was mentioned without comment, and of course with no attempt to draw conclusions. It’s left to you and me to tell this story when and wherever we get a chance. Of course, it means that Americans will have to rethink how we conduct ourselves in the international arena, how we treat offenders in our society – many such things must be examined and re-examined, and we shouldn’t shrink from this challenge. The alternative is to go on dehumanizing our servicemen and women, who are already committing suicide at an appalling rate. And why should we shrink from it, when if we accept it we can build a far better world based on the true recognition of who we are.

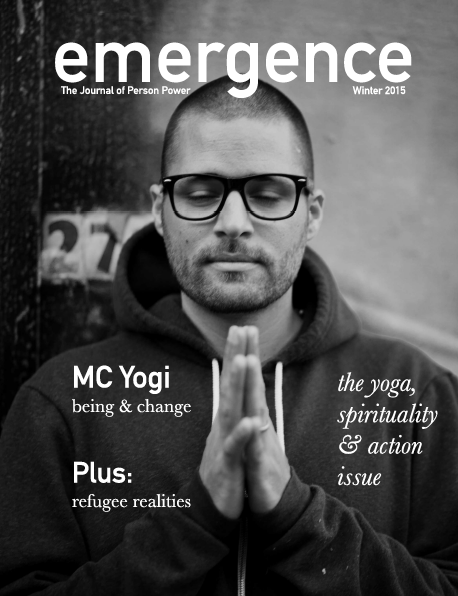

MC Yogi appears on the cover of the Winter 2015/2016 issue of Emergence, which revolves around yoga, spirituality, and action.

MC Yogi appears on the cover of the Winter 2015/2016 issue of Emergence, which revolves around yoga, spirituality, and action. Although these news stories highlighted legitimate school behavioral management concerns, they provide little in way of explaining how behavior change could function in school settings. They framed behavior change as a choice; that is, students might logically choose not to engage in these behaviors again because of harsh consequences (this is a part of the theory of reasoned action). They stressed the use of power to force behavior change. Ultimately, they provided little incentive for readers to consider engaging in empathy, understanding, or compassion for all people involved, so that readers might develop a more comprehensive understanding of behavior change.

Although these news stories highlighted legitimate school behavioral management concerns, they provide little in way of explaining how behavior change could function in school settings. They framed behavior change as a choice; that is, students might logically choose not to engage in these behaviors again because of harsh consequences (this is a part of the theory of reasoned action). They stressed the use of power to force behavior change. Ultimately, they provided little incentive for readers to consider engaging in empathy, understanding, or compassion for all people involved, so that readers might develop a more comprehensive understanding of behavior change.