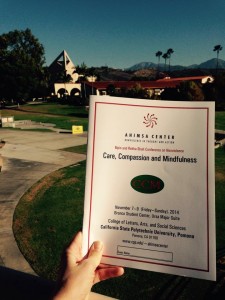

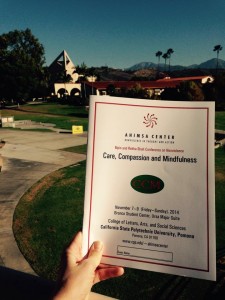

I recently had the opportunity to attend the Ahimsa Center biannual conference on nonviolence at California Polytechnic University Pomona, and in this blog post I would like to share with you a round-up of the conference presentations and a little about my own experience, takeaways, reflections and lingering questions.

-Stephanie Knox Cubbon, Metta’s Director of Education

“Compassion is the radicalism of our time.”

“Compassion is the radicalism of our time.”

-His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

Background

The Ahimsa Center was founded in 2004 by Dr. Tara Sethia, a distinguished scholar, author, nonviolence practitioner and history professor at CSU Pomona. In addition to hosting the conference, the center houses the minor in Nonviolence Studies which Dr. Sethia coordinates, a biannual summer fellowship for K-12 educators to learn about nonviolence, and numerous other educational programs and outreach activities on campus and in the local community. This year’s conference theme was Care, Compassion and Mindfulness, and the panelists included educators, religious scholars, psychologists, designers, and artists – people from a wide variety of fields who are incorporating these themes into their work. The interdisciplinary approach led to an enriching cross-pollination of ideas and allowed each of us to bring in new perspectives from other fields.

Some of the key themes during the conference included:

Happiness and fulfillment come from within us

In his opening talk, Dr. Allan Wallace of the Santa Barbara Institute of Consciousness Studies talked about “cultivating conative intelligence.” He explained conation as the mental faculty of purpose, desire, will to perform an action, or volition. He described conative unintelligence as when we try to escape suffering, we run right towards it, primarily through craving and attachment (which causes more suffering).

What does this have to do with happiness? He discussed two types of happiness, hedonic happiness, the stimulus-driven pleasure derived from what we get from the world (such as through food, sex, and material goods), and eudaimonic or genuine happiness, which is derived from what we bring to the world. Dr. Wallace explained, “As long as we are seeking happiness through hedonic pleasures, we are gamblers and the house always wins.” The materialistic worldview and consumer way of life that we find ourselves in currently (the “old story”) is hedonistic, and is essentially doomed. Dr. Wallace urged us to develop a richer vision of a good life, which includes meditation (which he compared to “mental hygiene”) as well as shifting our priorities towards finding purpose and meaning in life. If you know Metta’s work, this should sound familiar! What Dr. Wallace was saying resonates with the second of Metta’s five propositions in our vision, namely that we cannot be fulfilled through consumption (as much as the media would like us to believe), and can only find fulfillment through discovering our own person power and through the expansion of our relationships. Check out Metta’s course on the Meaning of Life for more on that subject!

We are mind, body and spirit

Shamini Jain shared with us the fascinating research she is doing through the Consciousness and Healing Initiative to research the “biofield” therapies – energy therapies such as reiki, acupuncture, and others that work with what ancient healing traditions call the energy body (prana, chi, qi). Emphasizing that we are mind, body and spirit, she said all of these modalities have some similarities, such as:

- the assumptions that consciousness is primary and that healing takes place on all levels (mind, body & spirit)

- the practitioner engages in grounding, letting go of ego and connecting with universal energy

- the practitioner uses gentle touch that directs energy flow through the system, and

- the practitioner consciously intends for the patient’s highest good.

Her research attempts to bridge the gap between ancient traditions and modern science, which is an important contribution to the field of nonviolence!

Mindfulness and Moral Injury

Lisa Dale Miller talked about her work using mindfulness with veterans to heal moral injury, what she described as, in contrast to PTSD, the trauma induced by witnessing or actually compromising one’s own morals judgment. For example, moral injury may result from the deep grief and regret a soldier might feel for carrying out orders that go against their moral compass. In her work, she has found a “toolbox of awakened presence” that veterans can self-apply to heal from moral injury, such as nonharming, nonhatred, nongreed, and kind recognition to whatever comes. Her presentation made me reflect on the role that we can play to support the members in our communties who may be suffering from this kind of trauma, and how we might contribute to the collective healing needed from our engagement in decades of war.

Peace Ecology

Randall Amster, author of the new book Peace Ecology, shared with us about ethics of care for the Earth, and discussed the peacebuilding and transformational potential of the Earth, since it’s what we all have in common. He discussed the relationship between human-to-human and human-environmental conflict, and asked the question “How can we alter the cycle (of violence)?” While he acknowledged that window of opportunity for change is closing rapidly in terms of our environmental challenges, he holds the view that we still have potential to change if we can muster the will and take action.

Mindful Parenting

Mindful parenting was also a theme, and Kozo Hattori of Raising Compassionate Boys told us about his efforts to raise instill compassion in his sons. He humbly told his own struggles as a parent to raise compassionate boys in our society, and expressed how mistakes are opportunities to role model compassion and forgiveness. His presentation touched upon themes of gender and how societally-imposed gender roles are hurtful to all genders.

Discipline, selfless service, nonattachment

Themes from Vedantic philosophy, Buddhism, yoga, and Jainism also appeared throughout the conference. Chris Chapple of Loyola Marymount University (which has the first Master of Arts program in Yoga Studies in the US) discussed the four immeasureables (lovingkindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity) and the Bhagavad Gita. One of the themes that stood out to me was tapas – the will to develop a rhythm of purification, essentially spiritual discipline to let go and burn away (tapas literally means fire) anything that is keeping you from your true self, your highest potential. In my own life and practice lately, I have been contemplating this theme a lot, as we live in a society that generally tries to pull us away from, rather than support us in, our spiritual practice. In order to discover our own person power, we have to create some effort. The state of our world requires us to be disciplined with our intentions and actions, and it’s a helpful reminder that all of the wisdom traditions emphasize discipline and an important part of the spiritual path.

Dr. Padmanabh Jain, professor emeritus of UC Berkeley, discussed the connection between ahimsa and aparigraha (nonclinging or nonattachment), saying that ahimsa is impossible without aparigraha, and that everything in excess is himsa, harming or violence. This made me reflect on our current culture: What does this say about our society, which puts an emphasis on overconsumption and excess? What might happen if we think about our overconsumption as a form of violence? Dr. Jain encouraged us to consider that we already have enough – another helpful reminder.

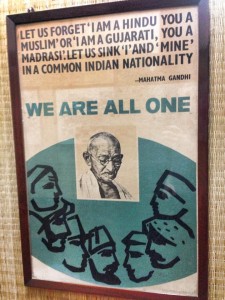

Gandhi and Restorative Justice

Dr. Veena Howard shared about Gandhi’s strategy for restorative justice and how we desperately need this approach in the US, which has the highest prison population in the world. Gandhi thought of crime as disease, and that as a society we need to defeat crime but not criminals, and to understand and take responsibility for the conditions we are collectively creating that result crime. Click here to access Metta’s self-study resources on restorative justice and nonviolence.

Education

The last panel of the conference was on mindfulness in education, which gave me much food for thought. Christian Bracho asked us to remember the teachers who impacted us the most, and said in all likelihood, it wasn’t a teacher who knew the content, but it was someone who really cared. For me this rang true, as I immediately thought of Mademoiselle Konig and Mr. Hoffman, my high school French and history teachers, who were two of the most caring teachers I encountered in my scholastic career. Who were the teachers who impacted you the most?

Another idea that emerged from the panel was that of peer coaching, and this has been on my mind a lot with respect to peace education. A lot of times, those of us who are doing peace and nonviolence education may feel isolated, like we are the only ones doing it, and we don’t really have the means to reflect on our own practice and get new ideas. So my personal goal after this conference is:

a) To start a peer peace education meetup/coaching group in San Diego, where I live (and if you’re reading this, why not start one where you are?)

b) If you are reading this blog and this idea interests you, I would also consider starting a monthly Google Hangout for those of us who may be in different places to connect virtually to discuss peace and nonviolence education. Interested? Email me! education@mettacenter.org

Vikas Shrivastava talked about the Mindful School Project, and what struck me most about his presentation is that he shared about lessons learned from what he called “a disaster.” Rather than share with us a success story (which is often the case in public presentations), he shared about what didn’t work. He talked about our tendency to project-ify and certify everything, to make everything into a framework that we can then sell and replicate, but in his opinion this is not necessarily the best way forward. He offered some suggestions, such as:

- Working within your realm of influence (and not feeling the need to “scale up”)

- Let go of the “franchise dream” (creating something that can be replicated)

- Stay focused on the work you have

- Serve at the request of others

- Your life is your journey

In my notes I wrote “more teacher training institutes? Community workshops?” as ideas the percolated during his talk. In a discussion after the panel, some of the Ahimsa Center graduates (of the teacher training institute) discussed the need for more professional development opportunities in this area, which has my wheels churning.

Selfless Service, Gift Ecology

Selfless Service, Gift Ecology

Finally, the closing session was with the ever-inspiring Nipun Mehta of ServiceSpace.org, who discussed how being consumers is not our highest potential as human beings, and we unlock our greatest potential when we engage in selfless service. He also talked about the power of internal transformation, and how Gandhi’s internal transformation was really the engine of India’s liberation. He shared with us the principles of Service Space, which are:

- Be volunteer run – unleash the power of many to see the collective intelligence that emerges

- Don’t fundraise – unleash a gift ecology, and people’s cup of gratitude overflows

- Focus on the small – unleash the ripple effect

He also talked about our need to think of different kinds of capital other than money, such as time, and how we are blind to other forms of “capital.” He urged us to think differently about abundance, saying none of us were born into this world empty-handed. To help broaden our ideas of capital and abundance, he invited us to ask ourselves, “How can I help people today? What do we have, and how can we work with what we have?” Some of the best conversations took place around the meals that were part of the conference program (which were all vegetarian! You know you are at a good conference when vegan cupcakes are on the menu :). The mealtimes gave us lots of opportunities to connect, network, and engage in rich discussions around these themes. I left the conference feeling very invigorated, with lots of questions, and with lots of new friends and connections with whom I can grapple with these questions.

********************************

As I returned home to my neighborhood, brimming with inspiration from the weekend, I heard the news that the remains of the 43 missing students in Mexico had been found. The students were studying to be teachers, and were known for their activism around social justice issues, reminding me that we live in a world where teaching and learning about the state of the world – and critiquing it – can get you killed. As the optimism and inspiration I was filled with met the despair and pain I felt from acknowledging this reality, I was reminded that we have so much work to do. But I feel prepared, and charged, to do that work. It’s our responsibility.

Just leaving the Gandhi House “Mani Bhavan,” in central Mumbai… Words aren’t really gonna do it here, but I’ll try anyways:

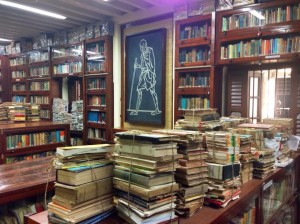

Just leaving the Gandhi House “Mani Bhavan,” in central Mumbai… Words aren’t really gonna do it here, but I’ll try anyways: oday, the building, (a 4 story mansion on an amazingly quiet street for Mumbai), serves as the homely Gandhi Museum. It holds the largest collection of books about Gandhi, read by Gandhi, and written by Gandhi. His personal spinning wheel is housed here, along with many other items that he used during his stays. There are extensive timelines, photographs, & texts about his life and India’s fight for liberation. My favorite part however, (though I don’t think I was supposed to be there), was on the roof, where Gandhiji’s big canvas tent was often set up outside of the monsoon season.

oday, the building, (a 4 story mansion on an amazingly quiet street for Mumbai), serves as the homely Gandhi Museum. It holds the largest collection of books about Gandhi, read by Gandhi, and written by Gandhi. His personal spinning wheel is housed here, along with many other items that he used during his stays. There are extensive timelines, photographs, & texts about his life and India’s fight for liberation. My favorite part however, (though I don’t think I was supposed to be there), was on the roof, where Gandhiji’s big canvas tent was often set up outside of the monsoon season.