By Mercedes Mack

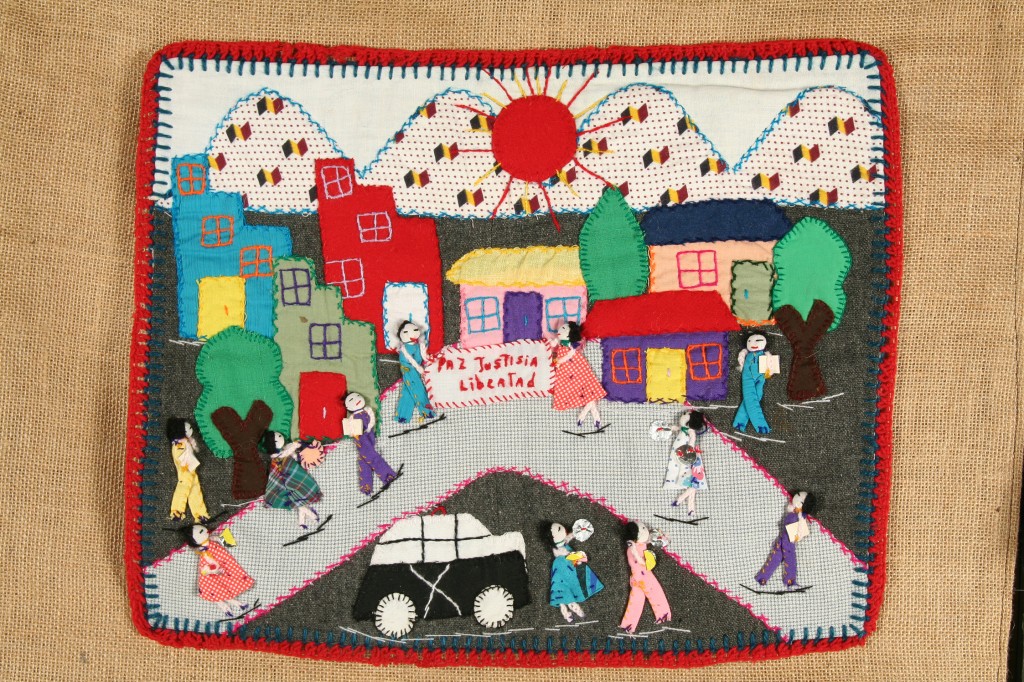

Arpillera, via the Royal Alberta Museum.

Arpillera, via the Royal Alberta Museum.

“At eight o’clock that evening, however, the city came to sudden life. In one neighborhood after another, a faint metallic clanking began, rising to a crescendo as people began to beat on pots and pans… May 11 was an explosion of joy and excitement, because people were so amazed that they were raising their voices-that they were speaking out.”

-Excerpt from A Force More Powerful

In honor of Chile’s Independence Day on September 18, I would like to reflect on the creativity exemplified in Chile’s 17 year nonviolent movement. Why is creativity important in a nonviolent struggle? At its essence, nonviolence is a creative solution to violence. Creativity allows for flexibility and innovation in strategy and messaging. Creativity also allows for the inclusion of all levels of society, reaching farther than just those that are willing to physically protest. Chile’s movement is a beautiful example of creativity and strength in the face of repression and cultural destruction.

In May 1983, union leaders called for a national strike in Santiago to protest Pinochet’s rule. As the strike date approached, the threat of very violent suppression by the military increased. Protest leaders called it off and instead decided to hold a National Day of Protest in place of a generalized strike. Leaders thought it would be a safer alternative and provoke less repression from police forces. As soon as night fell, people filled the streets of Santiago in protest. Those who did not protest in the streets took up pots and pans and struck them to make noise. Thousands of Chileans participated in the Day of Protest. The police tried to disperse the crowd-in doing so, two civilians were killed, tear gas was dropped and 600 people were arrested. A Force More Powerful describes the protest on May 11 as a watershed moment. A future without Pinochet was collectively realized that night. As the pots and pans clanged, and people protested in the streets of Santiago, Chileans everywhere were no longer part of a suppressed minority. An opposition broke through the silence, and there was no going back.

The ways in which Chileans contributed to the movement were extremely creative. In the beginning, police pushback was very strong. Protesters created methods of resistance that made it difficult for police to suppress, such as a “slow down” in which citizens walked and drove slowly at a designated time in order to protest Pinochet’s rule. The “slow down” was noted by A Force More Powerful as an event that fueled Chilean’s awareness of their majority and solidarity against Pinochet’s rule. As Chileans collectively slowed down during the day, and the sound of pots and pans clanged louder and louder during the nights, Chileans carved out a space within institutionalized restriction to resist.

One of the most inspiring veins of involvement was through the creation of arpilleras (shown in images in this post). Arpilleras were a political craft created by Chilean women during Pinochet’s rule. Originally they were made to protest the disappearance of loved ones, but later evolved into a folk art distinctive of that era. The handmade tapestries depicted scenes of daily life. Together women sewed the stories of their time: disappeared loved ones, scenes they have witnessed, stories of their past, stills of daily life in Pinochet’s Chile. Arpilleras were sold and thus the stories they depicted became mobile. They moved throughout Chile, undetected, encouraging solidarity, resistance and cultural preservation.

Chilean arpillera. Photo by Colin Peck.

Chilean arpillera. Photo by Colin Peck.

As Nadine Bloch writes,

“As the arpilleraistas gathered, often in church sanctuaries, the threads of their handiwork not only provided income to support their families, but also sewed together a growing consciousness of their own power. The craft provided a very accessible and low-risk entry point to the movement for many, while preserving collective memory and building capacity to go public with their demands, both on the political and home fronts — confronting the dictatorship and later the culture of machismo itself.”

The creation of arpilleras is also an example of constructive program. Coined by Gandhi, constructive program is a form of nonviolent action taken within the community to build structures, systems, processes or resources that are positive alternatives to oppression. As a constructive program arpilleras created a way -outside of the regime– for women to support their families and for the community to share and preserve a people’s history.

Students protest by dragging their desks into the school quad during the 2006 “Penguin Revolution.” (Photo by antitezo.)

Students protest by dragging their desks into the school quad during the 2006 “Penguin Revolution.” (Photo by antitezo.)

The tradition of creative resistance has gone on. More recently, in 2006 students requested education reform with an equally creative force. Dubbed the “Penguin Revolution,” students would pull their desks onto the quad and sit in solidarity. In addition to massive marches of thousands of people, the movement has used kiss-a-thons, hunger strikes, and dialogue with government. As part of her re-election campaign, President Michele Bachelet has announced an education reform package that addresses some of the concerns of the movement- More universities, expanding free education for students and increased funding for Kindergaten.

There is a common misconception that there is a formula, or “one way” for nonviolence to occur and be successful. The Chilean movements, past and present, are wonderful examples, rich in innovation and creativity, that best exemplify the limitless ways in which solidarity and resistance can be expressed that work around an initial fear of repression as well as education of people not already involved in the movement.

If you would like to know about the Chilean Nonviolent movement in more depth, we recommend the websites below:

Saying NO to Pinchet’s Dictatorship Through Nonviolence

Chileans Overthrow Pinochet Regime, 1983-1988

If you would like to read more about Chilean ariplleras, we recommend the websites below:

Weavings of Resistance

How Chile’s Mother’s Resisted

Art of Conflict Transformation Gallery

If you are interested in Chile’s current nonviolent movement surrounding education reform, please see the links below:

Student Leaders Reinvent the Movement

Palestinian children try to pull a praying carpet out from the rubble of the Imam Shafi’i Mosque in Gaza City, Aug. 2, 2014. (Photo: Sergey Ponomarev / The New York Times)

Palestinian children try to pull a praying carpet out from the rubble of the Imam Shafi’i Mosque in Gaza City, Aug. 2, 2014. (Photo: Sergey Ponomarev / The New York Times)