By Stephanie Van Hook

“I am praying for the light that will dispel the darkness; let all those with a living faith in nonviolence join me in the prayer.” M.K. Gandhi

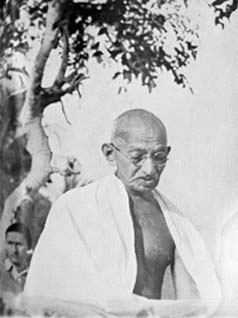

Gandhi was once given a seemingly impossible scenario: what would he do if a plane were flying over his ashram to bomb him? He rose to the challenge with an equally challenging answer: he would pray for the pilot. Some may take Gandhi’s response as preposterous. I argue, however, that his call to prayer was consistent with his vision of nonviolent strategy, for at least three reasons.

Reason 1: It meets the escalation of physical force with soul force.

Nonviolence requires strategic thinking; in other words, it requires a knowing of how to switch from one mode of operation to another in response to how the conflict is progressing. When a conflict escalates, a strategic response should also be prepared to escalate, not just with new tactics, but in the depth of the nonviolence itself. Dr. King echoes this idea in his Dream speech, that the freedom struggle would meet “physical force with soul force.”

It is important to grasp that Gandhi did not think that nonviolence was just of body alone. He called that the “nonviolence of the weak.” In his view, it was a practice of the soul, a quality of God, that could be cultivated in thought and word as well as deed, especially because thought is so tightly woven into deed. Even the word he coined for active nonviolent resistance shed light on this principle: Satyagraha, from sat meaning truth, the good, as well as that which is; and a-graha meaning to cling to. Would he discard the principle of clinging to reality, to Truth that was to him God, at the time of his imminent death? He was certainly put to the test when assassinated by the bullets of a fanatic, he passed that test, repeating the name of God as he lay dying.

Further, we should be wary of taking Gandhi’s statement out of the context of conflict escalation. He was not asked what he might have done to resist this events leading to this moment –he responded to what he would do in an “impossible” situation, when it seems one has no nonviolent choices left.

Reason 2: It overcomes the tendency toward fear and flight.

Coming from the perspective that nonviolence is a quality of spirit, of the soul, we see that it is something very different from a force limited to the physical dimension alone. In a world of violence, our resources and options are limited (in the present context, “bomb or do nothing”). We have little patience to draw from and it quickly dries up; any optimistic thoughts we had are quickly replaced by pessimism and cynical thinking and we think we are obligated to follow our fight or flight reactions because, when we look around us in this limited vision, this is all we have available. When we strive to cultivate nonviolence in word, thought and deed, however, we begin to explore and benefit from our inner resources, which Gandhi would tell us are infinite.

David Dellinger recounts the story of marchers in the African American freedom struggle in the early 1960s in Birmingham. When marchers were unexpectedly confronted by a line of police officers and firemen with dogs and hoses, the activists knelt down on the ground and began praying. One protester said that the group then felt “spiritually intoxicated,” without fear. As they got up and continued to walk on, the men behind the fire hoses found themselves somehow unable to respond, despite frantic calls from the police commissioner to “turn on the hoses.”

There is always a nonviolent response in our tool-kit; it is really only a matter of whether we feel empowered to use those tools. For those who were watching those marchers, it might have looked as though they had no choice but to flee or fight back, but they knew where to go within themselves to find another way.

Gandhi’s response to the questioner, in only a few short words, gives us a window into this wellspring of potential within us. He was encouraging us to have confidence. With infinite, renewable resources at our disposal, we need not worry about running out of choices; we need only to worry about our own courage to make the right ones. It is very subtle, but what out of context could look like passivity is actually a statement of immense inner strength and daring: a refusal to be corrupted by an impulse toward fear and hatred.

Reason 3: It is constructive as well as a form of resistance.

Nonviolence is a power: a form of energy that can be harnessed, redirected and transformed. At the Metta Center for Nonviolence, our definition, based on Gandhi’s experiments is that it is the conversion of a negative drive, such as anger, fear, or greed, into a positive one. The work to channel strong energy as it moves through our words, thoughts and deeds is the practice itself, the hard, lifelong work of the nonviolent actor to perfect her skill. It goes to reinforce that nonviolence is as much an interior process as an exterior strategy and that these two aspects– outer struggle and inner work– complete each other. Gandhi’s prayer is an expression of this unity of action between the inner and the outer realms. It was a form of resistance against the corruption of his heart on one hand, and a call to those in his movement to maintain personal strength, even when all seems hopeless– because a movement convinced of its inferiority is a movement that has already lost. Prayer can empower in a way that galvanizes the spirit of a movement by building up the human being from the inside out. It is the ultimate grassroots power. It is gaining access to, as Gandhi once wrote, a force in oneself that “no power on earth can subdue.”

There is a true story that illustrates this idea. A Jewish woman during the Holocaust confides in a friend about the agony in her mind. She cannot sleep; she cannot eat; she cannot think. Her friend suggests that she should pray for Hitler. “Pray for Hitler? How could I? Why should I?” was her response. “Not that he should succeed,” the friend added: “but that God might awaken his heart.” When she saw her friend later and was asked if she tried it, she said she did, and added, “I don’t know if it did him any good; but it helped me.”

Prayer is powerful. Let no one still unconvinced say that it is only sentimental or irrelevant to movements. One of the most arresting images from the Egyptian popular uprising in Tahrir Square in in the 2011 “Arab Spring” was that of the protesters in prayer with the military. Five times a day, people united whether man or woman, military or protester. As we know, the military defected and joined the popular resistance movement; a few days later, Mubarak was on his way out. This is why we will find one of the world’s most respected nonviolent strategists Gene Sharp listing prayer and public worship in his famous list of 198 tactics of nonviolent action–plain and simple, because it works.

The Challenge and Promise of Prayer

Gandhi’s view of prayer, it should be noted, was actually quite specific. According to Michael Nagler, Gandhi had three conditions for prayer to be effective:

- One needs to be deeply concentrated.

- The prayer must be selfless.

- There must be some recognition that the power to which one prays is within, not outside, of oneself.

He thought it should be a “thing of the heart, not a thing of outward show,” nevertheless a thing that helps us to overcome our greatest fears and feelings of inadequacy. Moreover, Gandhi maintained that prayer honors our human capacity. In his words,

“A merely intellectual conception of the things of life is not enough. It is the spiritual conception that eludes the intellect, and which alone can give one satisfaction.”

As the United States prepares to harm people in Syria and exacerbate the conflict by dropping bombs on Syrian people, and as we struggle to intellectualize and rationalize our response, we need this neglected power of prayer.

How often I have wished or tried to pray so that others might change and I would not have to do anything. From the right people at the right time, that might work. But in the case of inflicting violence on others, as the U.S. is prepared to do once again, we might think differently about prayer. Gandhi felt that prayer works when asking for support in changing oneself: help me to overcome the fear of doing what is right; guide me to the path of service; help me to understand what I can do at times when I feel I am out of choices; nurture in me an ability to perceive the humanity in even the most ruthless among us; guide me to do what is right in tough situations and not lose my humanity in the process. We can pray for each other, that our prayers are heard by our inmost selves, that we are transformed from oppressor to healers; from fearful to fearless; from unimaginatively violent to creatively nonviolent.

Prayer should not lead us into passivity or complacency, but should propel us into creative action. Look up photos of Gandhi and prayer. You might find some images of him at his prayer meetings with eyes closed or hands in prayer position, but in the rest we see him hard at work, hands praying on the spinning wheel; hands praying with a pen; hands building a movement. He actually did spinning at the prayer meetings–the inner and outer work at the heart of the resistance movement. This should be a clue to us. Our nonviolent actions as a collective might—and should, I would argue—look different from one person to the next: we will all meet the challenge from the communities we inhabit and the skills we have cultivated; our diversity would be our strength. Nonetheless, action matters to prayer–this is the form our prayers must eventually embody if we take them seriously.

Borrowing some language from Rabbi Michael Lerner, may we cultivate “an ethos of love, generosity, and awe and wonder at the grandeur of the universe,” as we join together to pray with our hearts as well as our words and hands in the struggle to expose and remove our complicity from the violence of empire.

Another, more recent example of a nonviolent response to a threat happened in a Walmart parking lot in Tennessee. 92 years old at the time, Pauline Jacobi put her groceries in her car and was ready to leave the premises when a man opened up her passenger-side door, entered the car and pointed a gun at her. He demanded that she give him her money or he would shoot her. She refused outright. She instead told him that she was not afraid of death because she “would go straight to heaven.” Pauline then calmly spoke to him for 10 minutes about what she cared about the most before the man broke down in tears and said he wanted to change his life. Before getting out of the car, he was startled when she voluntarily gave him all the money she had–10 dollars. Pauline refused to be coerced by a severe threat and clung to her innate sense of dignity, power and yes, faith. Her act not only saved her life, it brought her closer to her would-be-attacker and transformed his life, not to mention inspiring countless others who hear her story, perhaps even to act with similar courage in the face of such contingencies.

Another, more recent example of a nonviolent response to a threat happened in a Walmart parking lot in Tennessee. 92 years old at the time, Pauline Jacobi put her groceries in her car and was ready to leave the premises when a man opened up her passenger-side door, entered the car and pointed a gun at her. He demanded that she give him her money or he would shoot her. She refused outright. She instead told him that she was not afraid of death because she “would go straight to heaven.” Pauline then calmly spoke to him for 10 minutes about what she cared about the most before the man broke down in tears and said he wanted to change his life. Before getting out of the car, he was startled when she voluntarily gave him all the money she had–10 dollars. Pauline refused to be coerced by a severe threat and clung to her innate sense of dignity, power and yes, faith. Her act not only saved her life, it brought her closer to her would-be-attacker and transformed his life, not to mention inspiring countless others who hear her story, perhaps even to act with similar courage in the face of such contingencies.

we become more insecure.

we become more insecure. When he realized that passivity was not an answer to solve the problem of foreign domination, he upheld nonviolent creative action. When he realized that untruth was the order of the day (even back then!), he upheld the principle of truth; instead of maintaining a vision of “the greatest good for the greatest number,” or a utilitarian approach to social uplift that required sacrificing some for the good of all, his motto was “the uplift of all,” sarvodaya. And he struggled to uphold these values in his personal life. This is the secret of security: like love, at its highest, it is not something that we receive; it is something that we do. And in doing security, in being secure and promoting the security of others, we find our own. It starts with the spirit, not the spy game. It takes a shift toward altruism, not a shift toward shutting down others and others and others and finally ourselves.

When he realized that passivity was not an answer to solve the problem of foreign domination, he upheld nonviolent creative action. When he realized that untruth was the order of the day (even back then!), he upheld the principle of truth; instead of maintaining a vision of “the greatest good for the greatest number,” or a utilitarian approach to social uplift that required sacrificing some for the good of all, his motto was “the uplift of all,” sarvodaya. And he struggled to uphold these values in his personal life. This is the secret of security: like love, at its highest, it is not something that we receive; it is something that we do. And in doing security, in being secure and promoting the security of others, we find our own. It starts with the spirit, not the spy game. It takes a shift toward altruism, not a shift toward shutting down others and others and others and finally ourselves.