Earlier this week, Hamid Karzai confirmed that the United States will build nine new military bases in Afghanistan, including a strategic base at the border with Iran, with White House spokesman Jay Carney assuring us that these nine new bases will not be permanent. Their role will mainly be to strengthen and train the Afghan military; our only question is whether they even entertained any non-military options? With our media, it’s hard to tell.

Earlier this week, Hamid Karzai confirmed that the United States will build nine new military bases in Afghanistan, including a strategic base at the border with Iran, with White House spokesman Jay Carney assuring us that these nine new bases will not be permanent. Their role will mainly be to strengthen and train the Afghan military; our only question is whether they even entertained any non-military options? With our media, it’s hard to tell.

One of the disservices done to the American public by the corporate media is the framing of this recent decision. As in numerous other reports, we are fed a series of top-down decisions like this one with language suggesting that they are in the best interest of American families and the strength of the nation, and that they are not open to discussion. As usual, the implicit bias from the top is that we citizens are ignorant and powerless; if they do not provide a violent, armed, militarized solution, the US has nothing else to offer. But it is their ignorance and powerlessness that we are seeing, not our own.

There is a Zen saying about a reed in the wind, how it bends while a ‘strong’ tree can break. This truth is echoed by the prolific folksinger, Ani Difranco when she notes in her inimitable way that “buildings and bridges are made to bend with the wind/ what doesn’t bend breaks.” It’s practical wisdom, and very pertinent. As more everyday citizens become interested in exploring nonviolent solutions worldwide, this short-sighted and deadly dichotomy between violence or passivity of the U.S. government exposes its fatal flaw—an inability or an unwillingness adapt and evolve with the growing consciousness of people around the world. Structures simply have to evolve as people grow in consciousness if they do not want to face obsolescence; we created them to serve us, after all, and we are an adaptive species. In other words, if our systems are rigid and violent, it is our responsibility to see that they adapt, or step aside. There is a growing consciousness of a co-creative, life sustaining spectrum that encourages empathy and solidarity and makes everyone safer. Our growing awareness of our interconnection, if only through technology and climate/ecological understanding, points a way out to us from destruction to restoration, from harming to healing, and from profiteering to peacebuilding.

Acting on this consciousness of nonviolence, and creating institutional structures to serve it will be a major step forward for everyone; and it is more than just a re-prioritization of our values: it’s a rediscovery of who we are.

Just as the consciousness of separation and force is embodied in military systems, with their ever more fantastic equipment and trained (that is, unfortunately, desensitized) men and women, the consciousness of peace and human solidarity is beginning to be embodied in cross-border ‘peace teams’, truth and reconciliation commissions, international courts, peace communities (like the few who are holding on right now in Colombia), peace research institutions, and more. If you haven’t heard about them, we are not surprised—they are not the stuff of today’s media. Or today’s policy.

But they are working. Behind the scenes, peace teams, for example, are bringing children abducted by paramilitary units back to their families, protecting the lives of threatened individuals or whole villages, monitoring historic peace agreements (as recently in Mindanao), and stanching rumors—those prolific causes of intercommunal violence. What if our government were instead to set up nine peace operation centers in Afghanistan, at a cost of just nine percent of the proposed bases, with training and jobs available for nonviolent conflict intervention? What if it were to create nine centers for women’s empowerment instead of forcing many Afghan women into prostitution, as inevitably happens around military bases? They could happily employ retrained military people who sense this far nobler use of their courage along with the veteran peacekeepers of Nonviolent Peaceforce, Peace Brigades International, and the other groups—all still at a small fraction of the cost of the proposed bases. What if, with the rest of those resources, we were to set up nine high-tech, free hospitals, nine Afghan-centered universities and libraries, and throw in nine hundred village schools into the bargain, still totaling less than nine military bases with US arms and trainers?

But they are working. Behind the scenes, peace teams, for example, are bringing children abducted by paramilitary units back to their families, protecting the lives of threatened individuals or whole villages, monitoring historic peace agreements (as recently in Mindanao), and stanching rumors—those prolific causes of intercommunal violence. What if our government were instead to set up nine peace operation centers in Afghanistan, at a cost of just nine percent of the proposed bases, with training and jobs available for nonviolent conflict intervention? What if it were to create nine centers for women’s empowerment instead of forcing many Afghan women into prostitution, as inevitably happens around military bases? They could happily employ retrained military people who sense this far nobler use of their courage along with the veteran peacekeepers of Nonviolent Peaceforce, Peace Brigades International, and the other groups—all still at a small fraction of the cost of the proposed bases. What if, with the rest of those resources, we were to set up nine high-tech, free hospitals, nine Afghan-centered universities and libraries, and throw in nine hundred village schools into the bargain, still totaling less than nine military bases with US arms and trainers?

Economist Kenneth Boulding was one of the great pioneers of peace research, and he often communicated his important findings with a sense of humor. According to Boulding’s First Law, “if something exists, then it is possible.” Our privilege and responsibility as citizens is to uphold the possible and bring these alternatives to the attention of the media, of policymakers, and everyone we can get ahold of. It is our duty to our country—if not to the rest of humanity—to make it perfectly clear that if our key institutions do not bend in this direction they will surely break.

* * *

Stephanie Van Hook is executive director of the Metta Center for Nonviolence (www.mettacenter.org), Michael N. Nagler is professor emeritus U.C. Berkeley and founder of the Metta Center for Nonviolence; they are syndicated by PeaceVoice.

Commentary distributed by Tom H. Hastings, Ed.D. Director, PeaceVoice Program, Oregon Peace Institute http://www.peacevoice.info/

It happens that Charles Baudelaire is one of my favorite poets. I absorbed the passion of his words through a strong woman, a French teacher. He is, generally, misogynist in his writing, but we read him for other reasons — subversive spiritual searching.

It happens that Charles Baudelaire is one of my favorite poets. I absorbed the passion of his words through a strong woman, a French teacher. He is, generally, misogynist in his writing, but we read him for other reasons — subversive spiritual searching.

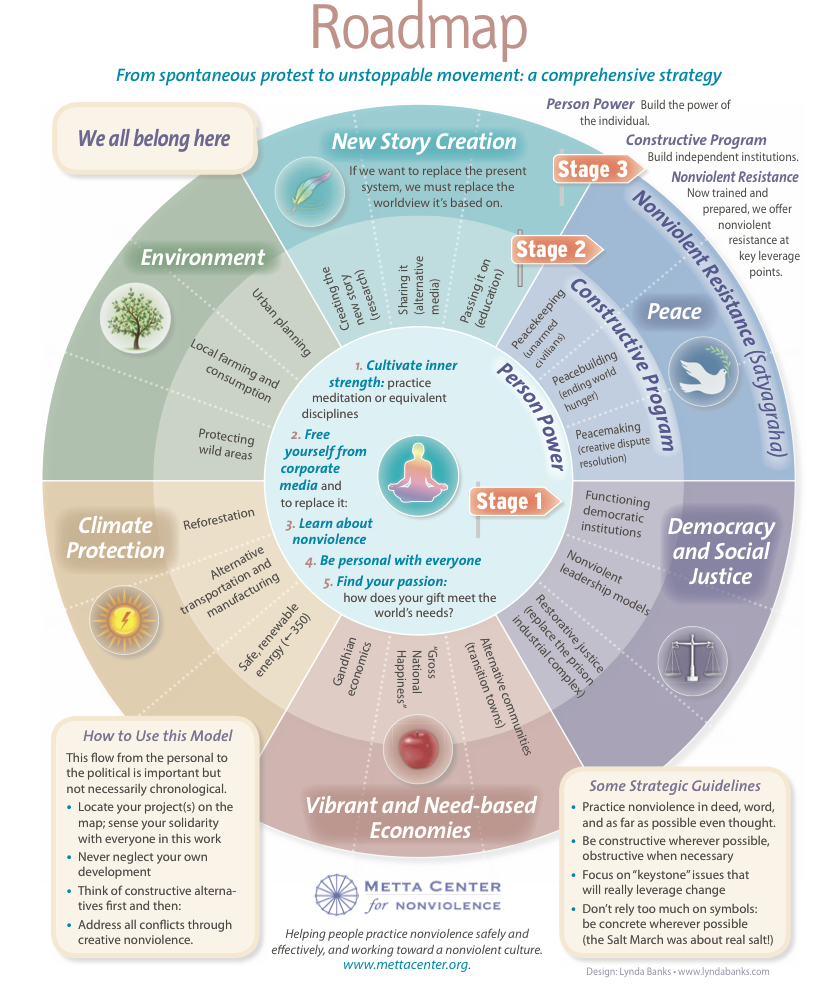

I’d rather not see a gun at all, but a statue of a man or a woman putting down the gun with one hand and reaching out with the other to something entirely different. That is nonviolence, that is feminism. It is not the negation of violence, it is not the negation of patriarchy, it is the affirmation of life, relationship and connection. It is a bell sounding the arrival of something else, no less real and in many ways, I would argue, more real because it is the more accurate enactment of our unity. There is so much to learn about these alternatives, from peace teams and shanti senas, to new economic models, to restorative justice, to new activisms, to new conceptions and practices of power, to

I’d rather not see a gun at all, but a statue of a man or a woman putting down the gun with one hand and reaching out with the other to something entirely different. That is nonviolence, that is feminism. It is not the negation of violence, it is not the negation of patriarchy, it is the affirmation of life, relationship and connection. It is a bell sounding the arrival of something else, no less real and in many ways, I would argue, more real because it is the more accurate enactment of our unity. There is so much to learn about these alternatives, from peace teams and shanti senas, to new economic models, to restorative justice, to new activisms, to new conceptions and practices of power, to